We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Anna Vescovi a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Anna thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

Before working in 3D design, I was a ballet dancer for about 15 years. Towards the end of my career, this became an all consuming profession. The expiration date comes early for high-performance athletes and by the time I was 19, a career change was on the horizon.

I didn’t have a clear idea of what to achieve next, but I was certain it had to be creative. Not much mind was paid to fine art until I moved to South Beach with Miami City Ballet. I worked a part time evening job at an upscale hotel restaurant, usually cluttered with couples, business executives and the occasional family. It was December 2018 when Art Basel had set up shop for its highly anticipated weekend. The restaurateurs who arrived were eccentrically dressed from all walks of life. I overheard glimpses of conversations relative to high-class press, design endeavors and secret collaborations while casually name-dropping elite clientele. After attending as many public events as I could find, I was hooked on the decadent world of design.

I retired from ballet that summer and began the fall semester at the Savannah College of Art and Design with a BFA in Fibers (the study of hand-crafted textile practices.) I spent four beautiful years working with my hands, learning about historic textile production, weaving on looms, screen printing fabric and practicing innovative material processes of the future.

Not only was I relieved that relevance in this industry wouldn’t expire as quickly as milk, but I was encouraged to mess up, explore and indulge as often as possible. The risk of changing careers remains the gift that keeps on giving.

Anna, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

You’ll find most young people entering their professional career had to face the pandemic through pivotal years of their studies. All university creatives were denied access to high quality machinery, exclusive technology and physical resources practically overnight. In the tactile world of fibers, this loss posed a logistical nightmare. We had to learn to adapt, and fast.

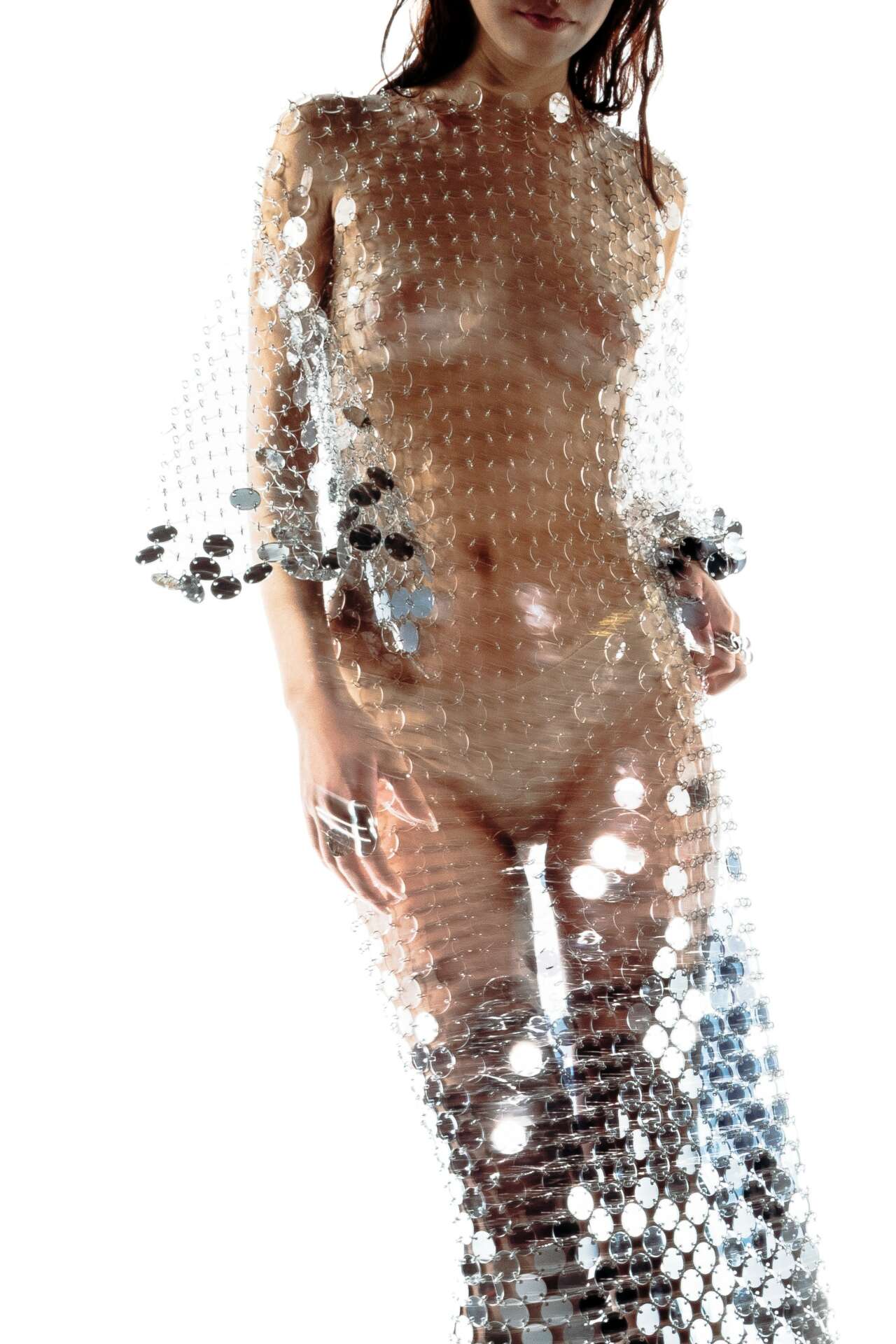

Many of my courses included weaving arts and training on other physical resources which were postponed until returning to campus. One notable course was still offered virtually and became a critical component in defining my design trajectory. Material Innovation provided digital printing access with the ability to safely ship our work from the lab to our doorstep. This is where I began flatbed printing on leather, creating laser cut samples, printing on fashion fabrics, etcetera. I finally began to see the potential of 2D work come alive in the real world. These experiments were later taken a step further. I began playing with unconventional, custom textile methods like assemblage, metal mesh, 3D printing and other innovative methods.

During senior year, my textile developments grew to new heights and classes resumed on campus. I created a senior collection of five textile-centric garments which garnered published recognition and awards from Vogue Runway, Surface Design Association, Council of Fashion Designers of America (CFDA), ArtsThread and GUCCI. Naturally, my curiosity didn’t stop there.

Two years later, I am working towards an MFA degree in Fashion and the Arts at Parsons Paris. Here, I will be honing craftsmanship in French couture in the realm of assemblage, embroidery, collection curation and fashion design. Some of these practices are extremely niche and only exist in the world of haute couture. Slow textile craftsmanship is an art strangled by the weight of unethical production and the rapid pace of disposable quality. Rather than immediately beginning my career post BFA, I chose to receive a second degree not only to enhance personal knowledge. It’s important to share the magic of slow-process production with my fellow generation; I want to spread a message that less really is more.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

The ballet world is notoriously cut throat. Career-breaking decisions often fall on the basis of cosmetic aesthetics, age, race and genetic physique. The body is continuously pushed to extreme limits yet many talents fall short due to visual differences categorized as imperfection. When training daily as an adolescent, my skewed perspective of competitive defense was at an all time high. Ballet can be a very lonely career without much constructive teamwork; a day in the studio means every man for themselves.

Within the textile community, differences are celebrated, ideas are shared, mistakes are encouraged and colleagues are cheered from the sidelines. I began to understand that a critique in class was not a failure, but instead an act of encouragement to think from a different perspective. Collaboration was not an opportunity to outshine others, but a way to grow and develop as a creative force and team. My class at SCAD was incredibly supportive; to share space with a group of students and faculty who acted as family became the way to best prepare for careers in the professional industry. It was the first time I felt so much strength on the basis of community.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

Emerging creatives require awareness that our work may contribute to the mass pollution crisis if not designed consciously with intention. It’s a constant battle against the boom in fast fashion and universal consumerism. This requires a keen focus on slower, high quality and often traditional means of production and techniques which are at risk of dying out in our fast paced world of trends and powerful conglomerates. Fewer, Better Things is an excellent read by Glenn Adamson, the former director of the Museum of Arts and Design. Each chapter focuses on the history of slow design practices which are often a long lasting, beautiful means of generational craftsmanship and care. Adamson’s book covers everything from intimate examples of textile and product design to niche methods of historic craft in a world unmarked by the digital age.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://annavescovidesign.com

- Instagram: @annavescovi

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/anna-maria-vescovi-972b00188/

Image Credits

(Cover Image) Garments/Art Direction: Anna Vescovi Photography: Aspen Forman Photo Assistant: Jenna Roy Talent: Mary Fant (Additional photo 1) Garments/Art Direction: Anna Vescovi Photography: Joe Tankersley Talent: Day Toscano (Additional photo 2) Garments/Art Direction: Anna Vescovi Photography/Film: Patrick Cox Photo Assistant: Emerson Scheerer Talent: Chloe Hill (Additional photo 3) Garments/Art Direction: Anna Vescovi Photography: Aspen Forman Photo Assistant: Jenna Roy Talent: Mary Fant (Additional photo 4) Headshot by Anthea Hill