We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Ann Rosenthal. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Ann below.

Ann, we appreciate you joining us today. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

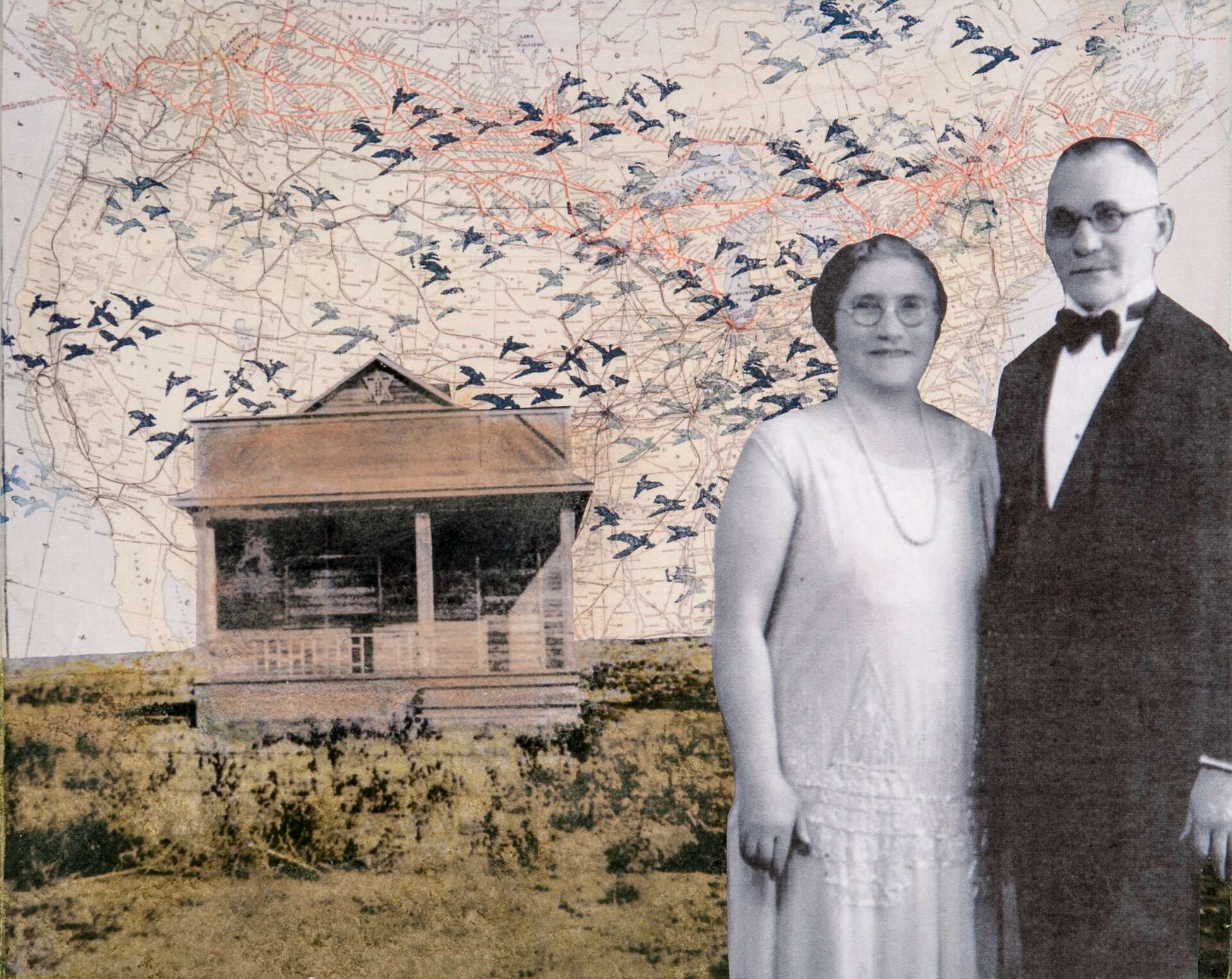

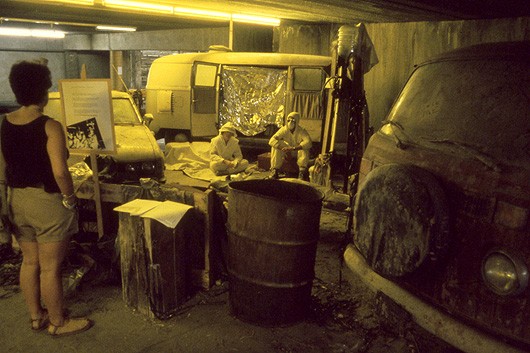

For over a decade, I collaborated with artist Steffi Domike on several art installations addressing a range of environmental issues. Our last project was the most ambitious in scope and concept. In 2013, environmental historian and writer Joel Greenberg was on a lecture tour to promote his book, “A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction.” Steffi and I heard him talk in Pittsburgh, where he encouraged people and institutions to develop programs marking the centenary of the bird’s extinction. Steffi and I decided to create an art installation, titled “Moving Targets,” to address the plight of this bird that numbered in the billions yet was wiped out in a period of 50 years. Our work became part of a larger, citywide effort, which included many cultural events and programs. “Moving Targets” paralleled the plight of the passenger pigeon with the coerced migrations of our mothers’ families to North America in the wake of the pogroms in the Ukraine. Dr. Ruth Fauman-Fichman researched our family histories, of which we knew little. While the ships, trains and telegraphs made it possible for millions of Jews to escape persecution, they also made possible the tracking and plunder of the passenger pigeon. The project linked both our families and the birds to ask why some groups—whether human or animal—are reduced to targets for extinction, whether intended or as a consequence of ignorance and greed. The installation was shown in five venues in four states. It included the “Passenger Pigeon Portrait Gallery” in which we invited 14 artists, each residing within the bird’s former nesting range, to create a “portrait” of the bird. We self-published an exhibition catalog through Blurb that includes five guest essays, including one by Joel Greenberg and one by Dr. Patricia DeMarco. The three images below are from the project. The first is titled “Safe Haven” and depicts my grandparents in their new home in a Jewish community in Alberta, Canada. The building was their synagogue and community center. In the sky is a flock of passenger pigeons and the railroad route that likely took my family from Halifax to Alberta. The second image is the Moving Targets installation in Pittsburgh, and the third is (left to right) my mother, me, and my sister. The orange blossoms suggest our home in Los Angeles.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your background and context? What are you most proud of?

I have been an artist since I could hold a pencil and, fortunately, my father encouraged my interest. As a child, I attended art classes at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art where my father was a member. I received my Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) from San Jose State University in 1979. At that time, few academic positions were available, and priority was given to men, so I decided to pursue being an artist on my own and not go on to obtaining an MFA. When I graduated, my partner Stephen Moore, who was also an artist, and I moved to Los Angeles, where we both grew up. We moved into an industrial loft owned by a friend. Below our second-floor living space, Stephen ran an experimental storefront gallery. At that time, we also became involved with a collaborative group of artists, UNARM, which addressed the threat of nuclear war. Our group produced several art installations, including one for a nuclear arts festival, “Target L.A.,” which was held in an abandoned parking garage in 1982 (first image below). Stephen and I grew up in the Cold War era during which “The Bomb” loomed large over our psyches—like the threat of terrorism and gun violence looms over us today. We experienced “Duck and Cover” drills in school and saw bomb shelters on front lawns. We wanted to address how the threat of nuclear war impacts us in ways that we might not be aware of—just as active shooter drills in schools are affecting young people’s mental health. Stephen and I went on to produce “Infinity City,” comprised of three art installations over a ten year period that addressed nuclear war and waste (second image below). I am most proud of having kept at this work for 40 years. When I began, environmental art was largely ignored by the art world, though there were many artists around the world who were doing it. Now, it has become almost a requirement to address social justice or environmental issues in one’s art. For most of the time I have worked as an artist, I received little support or funding. I have self-funded most of my projects through being a technical editor and through teaching. I am proud that I did eventually obtain my MFA from Carnegie Mellon University, 20 years after receiving my BFA. I left a very comfortable life in Seattle to move to Pittsburgh and attend the program, but I am glad I did and it was life-changing.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

My work has rarely been about selling my art. I am largely driven by the desire to wake people up and open their hearts. I try to prompt people to think about and question their relationship to nature and their responsibility to it, to reignite their love for this beautiful planet. Nature is not a storehouse of inert objects for our taking. Nature is alive with plants and animals who exist in living ecosystems on which they—and we—depend. Beyond what nature can provide for us, these are living beings and systems that have evolved over millennia and have the right to exist for their own sake. Hopefully, most of us have an understanding of social justice—that everyone deserves equal economic, political, and social rights. We need to expand that concept to include non-human nature—not only do all people deserve the opportunity to pursue a full and meaningful life, other life forms deserve the right to thrive without being undermined by human activities. Indigenous peoples have managed to coexist with nature. We can as well. We have replaced love and care for one another and the planet with buying stuff. We have been told that owning stuff will make us happy. It only makes us want more stuff, like a drug. We’ve reached the end of this road and it is time for a paradigm shift. We have the knowledge and the technology to transition to a more life-affirming existence. We just need the will to do it. I hope my work nudges people in that direction. To that end, my current paintings (the last two images below) depict salt water marshes that contain amazing biodiversity and protect coastlines, yet in 2023, the Supreme Court stripped federal protections from countless wetlands like these.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

Ever the teacher, I would like to share some resources that have informed my work and thinking over the years—my creative thinking as an artist and a human being. At the top of my list is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book “Braiding Sweetgrass.” I can’t recommend this enough. According to her website, Kimmerer “…is a mother, scientist, decorated professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.” Her book illustrates for me how a western, scientific worldview can coexist with indigenous knowledge and wisdom. The two are not opposed but can complement one another. I have learned a great deal from ecofeminist writers about the underlying historic biases behind Western thinking, which have led to our current environmental crises. Some of these authors include Vandana Shiva, Carolyn Merchant, and Val Plumwood. There are many more. Ecofeminism helped me understand how racism, sexism, classism, and naturism are related—that they are symptoms of the same disease—objectifying human and non-human “others” to justify their exploitation. A classic environmental text that I often come back to is Aldo Leopold’s “A Sand County Almanac,” which includes his concept of the “Land Ethic” and a story about “Thinking Like a Mountain.” A more recent book that I loved was “The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature” by J. Drew Lanham. In closing, I’d like to mention a book for which I was one of four editors: “Ecoart in Action: Activities, Case Studies, and Provocations for Classrooms and Communities.” It highlights 67 members of the Ecoart Network, a group I’ve been active in for over 20 years. It stands as a field guide offering practical solutions to critical environmental challenges.

Contact Info:

- Website: locusartstudio.org, lunapittsburgh.org, https://sites.google.com/view/luna-street-art/home

- Instagram: @locusartstudio

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ann.t.rosenthal/

- Youtube: @annrosenthal8194

- Other: Workshops and talks here: https://winslowartcenter.com/