We recently connected with Andreas Troeger and have shared our conversation below.

Andreas, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. So let’s jump to your mission – what’s the backstory behind how you developed the mission that drives your brand?

For me, the mission came out of necessity. I moved to New York from Munich Germany in the early ’90s with a camera, solid film school training, and a few video art pieces and film projects under my belt. I wasn’t chasing galleries or career milestones — I was drawn to document what mainstream culture overlooks: punk bands, underground performers, and the raw life on the streets.

Over time, I realized this work wasn’t just art — it was preservation. Stories that would disappear if no one captured them. Through photography, film, video art, and books, I focus on showing people as they are, not how they brand themselves. That’s the mission: truth, texture, and unfiltered presence.

It’s meaningful because I’ve felt invisible too. I’ve seen talented people ignored because they didn’t fit the mold. This mission gives space to those voices and pushes back against the noise and gatekeeping.

That’s when I know the work is doing what it’s supposed to do.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

As a visual artist, filmmaker, and author based in New York City, my creative path started in a very different world — working as a mainframe computer specialist. But disillusioned with corporate structures, I made a conscious break. I left that life behind and dove headfirst into underground performance and media art.

I studied film and television in Munich and later continued my education at NYU after moving to New York in 1992. Early on, I had the opportunity to work closely with Nam June Paik, considered the founder of video art and a key figure in the Fluxus movement. That relationship was pivotal — it led me deeper into video editing, camera work, and collaborations with avant-garde choreographers such as RaCoCo Dance Company led by Rachel Cohen, fine artist Olek, New York-based producer Garvey Rich, and international filmmaker Iara Lee. Since then, I’ve worked across media, from experimental film and video installations to live event documentation and photography.

In the mid-1990s, I became active in early internet culture through the activist project Name-Space. At its core, Name-Space aimed to challenge the corporate grip on the web by expanding the domain name system beyond the standard .com, .net. and .org. We pioneered the creation of new, expressive Top-Level Domains (TLDs) like .art, .film, and .travel — giving users more relevant and creative digital identities. What made it radical at the time was that anyone could propose their own TLD, and our independent server network would recognize and serve those domains. It wasn’t just a technical move — it was a cultural intervention to keep the internet open, expressive, and decentralized, long before those conversations hit the mainstream. But the project was ultimately doomed. Network Solutions, the company contracted by a U.S. government agency to manage the domain name system, held a monopoly and legal immunity that protected it from antitrust challenges.

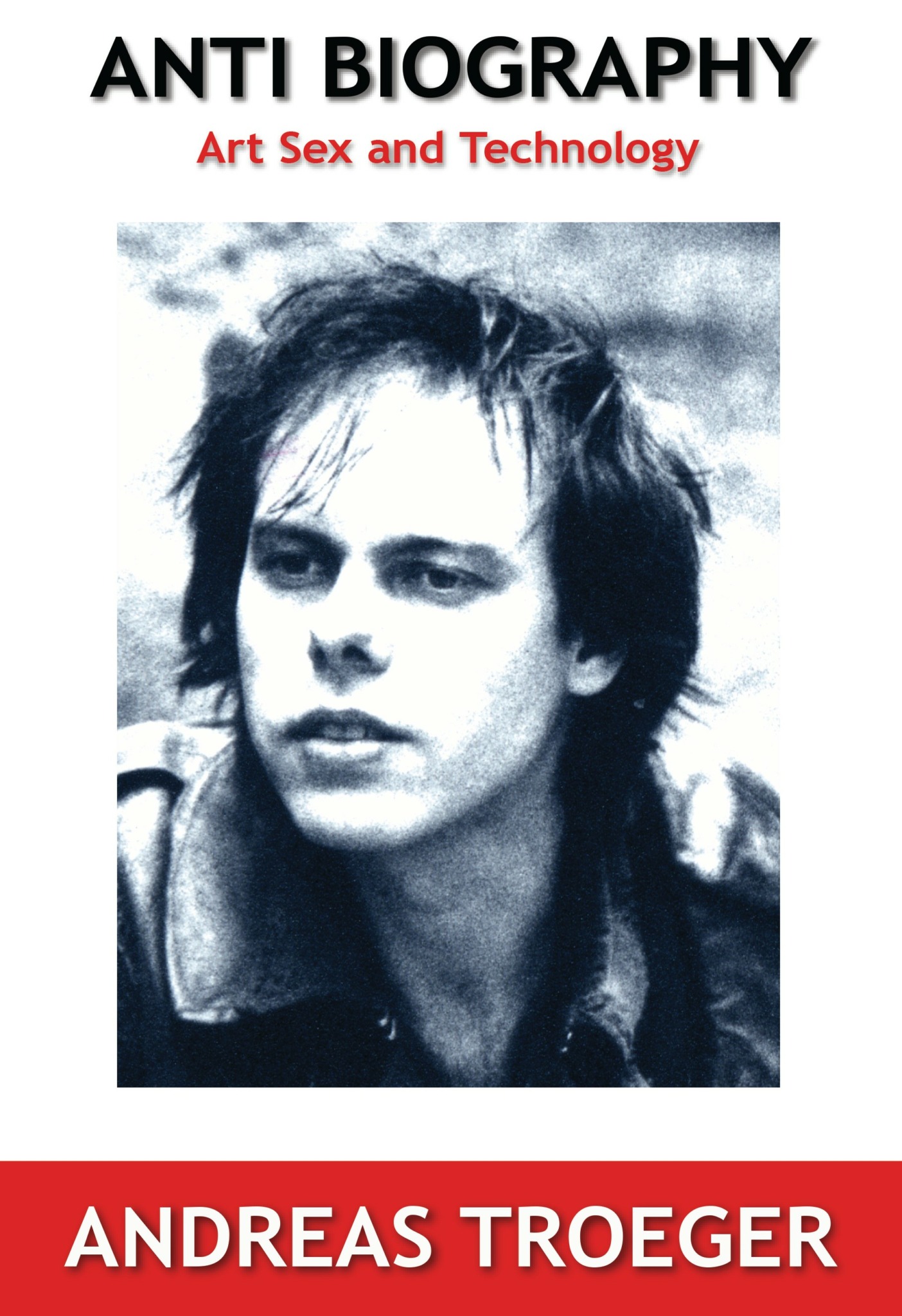

Between 1998 and 2019, I focused on projects that pushed back against cultural censorship and the art world’s tendency to sanitize expression. During this time, I directed and produced Kill the Artist — a raw, confrontational documentary exploring how underground filmmakers and taboo-breaking artists are often targeted by legal and moral suppression. The film includes rare footage and features artists like Richard Kern, Nick Zedd, Jörg Buttgereit, and Olaf Ittenbach, whose work challenges norms around sex, death, and transgression. In parallel, I developed the Anti Biography series — a fragmented, deeply personal book project that rejects the polished memoir format in favor of something more honest and grounded in real experience. I also continued to experiment with new media, blending analog and digital elements in video installations and virtual art that blurred the line between fact and fiction.

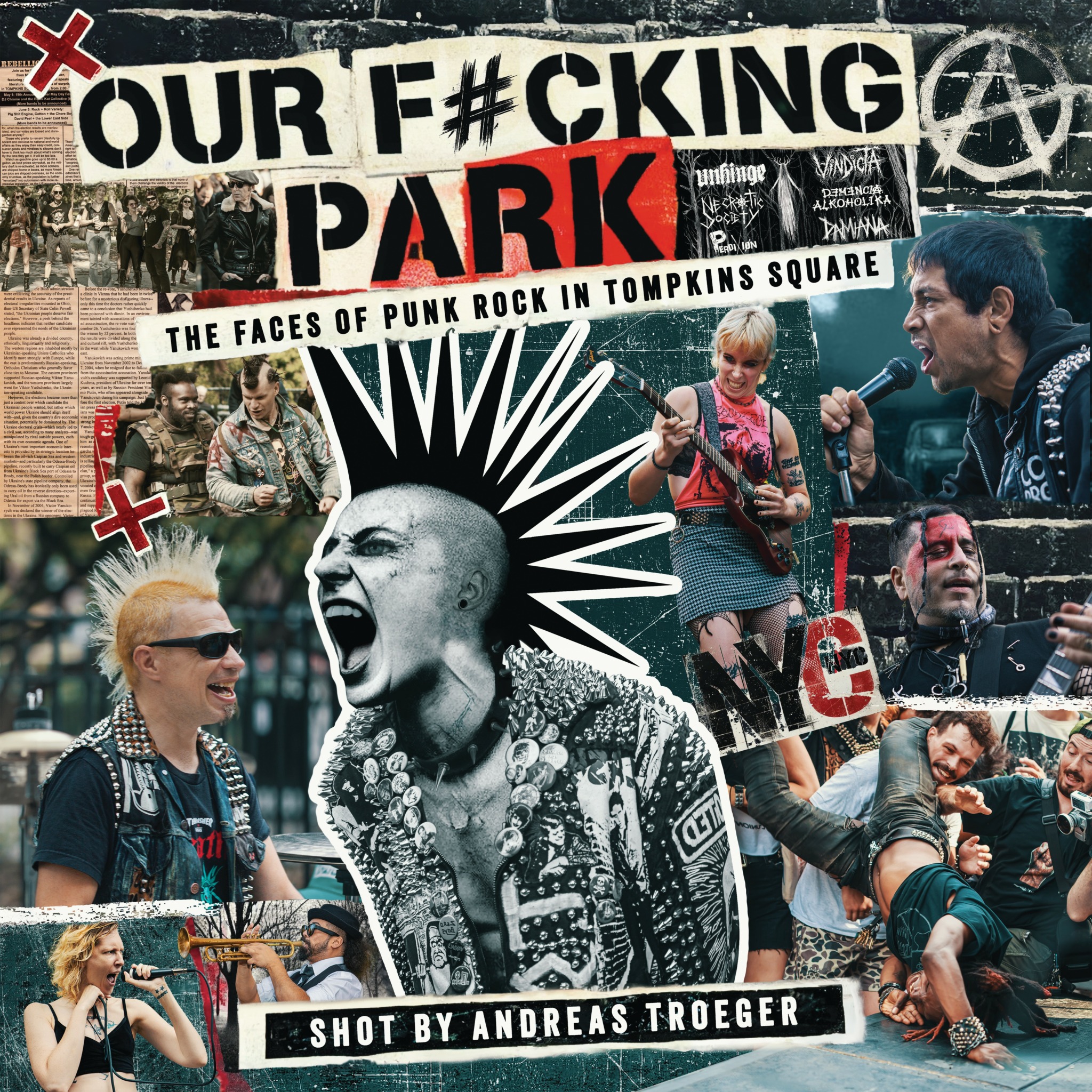

From 2019 to 2024, I documented the punk rock revival in Tompkins Square Park, photographing hundreds of shows. The result was OUR F#CKING PARK, a photo book capturing the raw energy, community, and resistance of one of New York’s last unpolished cultural spaces. It’s now available in local bookstores and museum shops.

What sets my work apart is that I don’t package a lifestyle or sell polish. I focus on truth — capturing people, movements, and moments that are often overlooked or erased. My collaborators usually come to me for something unfiltered and grounded. I’m proud that my work gives voice to scenes and individuals that don’t usually get one. Whether it’s a punk show, a downtown dance performance, or a personal video project, I’m there to catch the moment before it disappears.

More than anything, I want people to know this: my work is documentation with purpose. It’s not just about making art — it’s about preserving culture that matters.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

For me, it’s the independence — hands down. Being an artist means I don’t have to answer to a boss or follow someone else’s rules. I can think for myself, create on my own terms, and take risks that wouldn’t survive in a corporate setting. That freedom is everything. On top of that, having my work recognized by the community — not by institutions, but by the people who actually engage with it — that’s the real payoff. When someone sees value in what I do because it resonates, not because it was marketed to them, that’s when it all feels worth it.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can provide some insight – you never know who might benefit from the enlightenment.

I think many non-creatives struggle to understand what actually drives an artist — especially in a world that’s dominated by money, status, and the constant chase for financial security. From the outside, it can seem irrational, maybe even reckless, to dedicate your life to something that offers no guarantees. Creating without a clear path to recognition or profit doesn’t make sense in a system built around results and returns.

But what they often miss is that being an artist isn’t a lifestyle choice — it’s a compulsion, almost like a program quietly running in the background of everything you do. You don’t choose it — it’s wired into you. And when you try to override it, when you chase a “normal” path or force yourself to live by other people’s definitions of success, it doesn’t bring peace. It brings restlessness, frustration, even depression. There’s a deep sense of disconnection from yourself when you try to abandon that path.

What most people also don’t see is how long the road can be. Recognition can take years — sometimes decades — and in many cases, it never comes. Some artists only become known long after they’re gone. But that’s not really the point. The point is the work — and the hope that something you made might matter. That a photograph, a book, a film might stop someone in their tracks, shift their thinking, or let them feel seen. That your work might outlive you and still be saying something long after you’re gone.

That’s the real reward — not the applause, not the money, but knowing you created something honest enough to leave a mark.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.TechnologyArtist.art

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/TechnologyArtist

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TechnologyArtist

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/atroeger/

- Twitter: https://x.com/TekArtist

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@technologyartist8917

- Other: Video portfolio:

https://vimeo.com/technologyartistAmazon author page:

https://www.amazon.com/stores/Andreas-Troeger/author/B0DVMCPBWT?ref=ap_rdr&isDramIntegrated=true&shoppingPortalEnabled=true&ccs_id=b40225dc-8d7f-4802-a5ac-d6556afb61c3

Image Credits

Photo of Andreas Troeger – Photo by Chris McGrath, all other images are by me (Andreas Troeger)