Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Andrea Canter. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Andrea thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Do you think your parents have had a meaningful impact on you and your journey?

Tracing my current work as a visual artist (far) back to its real beginning, what my parents did “right” was provide exposure to the arts– probably in utero. Neither had any significant arts-related training as children or young adults (although my mother spent one elementary school summer taking children’s art classes in a day camp run by the great Grant Wood near her home town of Cedar Rapids, IA). Both were great fans of classical music and, from my earliest days, I heard music from my dad’s 78s and LPs, from Saturday radio broadcasts of Met Operas, and at live band concerts in the area. I also accompanied my parents to local art exhibits and museums. When we moved to Baltimore when I was starting elementary school, my father became an evening art student at the Baltimore Museum of Art, following an interest in painting that he was never able to pursue earlier. Soon my parents enrolled me in Saturday morning art classes for children at the Museum. Apparently I had impressed them with some preschool doodlings. Not only did these classes introduce me to a wide range of experiences with paint, my Saturday mornings also provided special time with my father–he would drive me downtown to class, spend the time visiting museum exhibits, then pick me up from my class to spend another half hour or so wandering through special collections, particularly the Impressionists and 20th century art. My early favorites were Matisse and Picasso. When I was ten, we moved from the East Coast metro environment to the Midwest college town of Iowa City. This might have derailed a potential career in the arts–there were no community art classes for children at the time and the University of Iowa Art Museum was yet to be built. However, the university setting also provided ongoing opportunities to enjoy music and theater, which my parents continued to encourage. My father continued painting in his basement “studio,” and although he actively discouraged an audience while painting, it was easy to see a painting’s progress, examine the tools he used, and enjoy the array of finished works that filled our walls. And (unintentionally, I think), I observed how one could have a professional career (my dad was a clinical psychology professor) while also engaging in the arts at a serious level. In addition to promoting my experience with paint, my parents also introduced me to photography with a gift of a Kodak Brownie for my 8th birthday, and although I had no professional training in photography until my 30s, I loved using that camera and subsequently more sophisticated upgrades, at first to document vacations and family events, and decades later, as a means of artistic expression.

My parents never pushed the arts on me or my musically talented brother–they offered exposure to the arts both at home and in the community as opportunities for enjoyment, learning, and self expression, not as career choices, although I know they would have supported us if we showed an inclination to make art or

music our lifework. But my father’s experience modeled the arts as a serious choice regardless of one’s vocation, and ultimately as an option in retirement. I worked as a public school psychologist for 30 years. I then spent more time on my photography as an artistic outlet. My dad’s final impact on my move into visual art, specifically painting, came when I mentioned to him that I was pondering how to incorporate paint into my abstract photography. He sent me to his long-neglected painting studio in the basement to retrieve paints, knives and brushes, giving me some small, quick demonstrations, sorting out the good/bad brushes and what few paints were still viable. After a few months I found I preferred paint without the photograph, and hoped to please my father with my efforts. He had worked in an abstract manner but never really left reality behind. He would examine my works, which he described as “wild” and requiring extended viewing to interpret. But he was clearly pleased I had found my way to paint. My mother always looked for something familiar, finding a bird in every painting. Parents can still do it “right” even if they don’t quite understand the product, by supporting the process.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

Briefly, I’m a retired school psychologist, living in Minneapolis since I came here for grad school in 1971. After seriously studying photography and not seriously studying ceramic sculpture at local community art centers in my 30s and early 40s, I moved into photojournalism during my early retirement years, primarily working with online outlets promoting local and national jazz and serving as photographer for the the Twin Cities Jazz Festival.

As I became more interested in using photography for abstract expression, I began contemplating combining photographs with acrylic paint. Yet as I started to use paint, I found I was far more interested in extending the use of paint without photography. (And for whatever reason, I did not turn to digital painting. I liked the feel of smearing the paint onto paper or canvas in real time.) Now I’ve been working (painting) out of a studio in the historic Casket Arts Building in the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District since 2018.

My art education: I have a long journey into art, starting with preschool home-based scribblings that must have suggested some talent or at least interest to my parents, who enrolled me in Saturday morning children’s art classes at the Baltimore Museum of Art in the mid 50s. After three years, we moved to Iowa City where, at the time, there was nothing similar for children outside of public school weekly art classes. Meanwhile I was getting more interested in photography after receiving a Kodak Brownie. I used the camera more as a documentary device, not artistic outlet. I did finally take one elective art class in high school, an intro to oil painting. I remember painting still lifes and not particularly enjoying it. In college I took a class in Art History, which I enjoyed, but, given it was 1970, there was little attention paid to Post World War II artists. I did study photography in the 1980s at an area art center with a protégé of Minor White, George Gambsky, which I believe was my formal education in composition that served me well as I moved into painting after retirement.

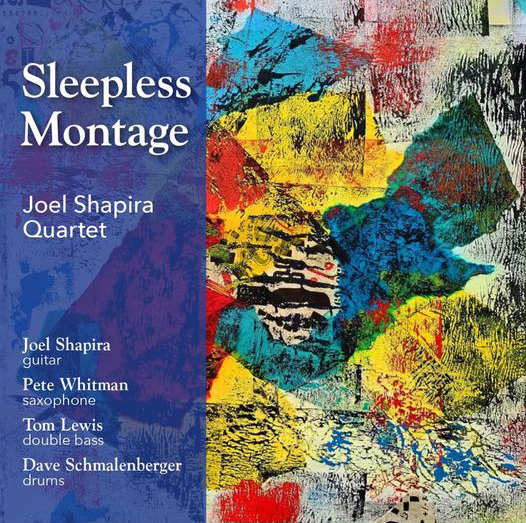

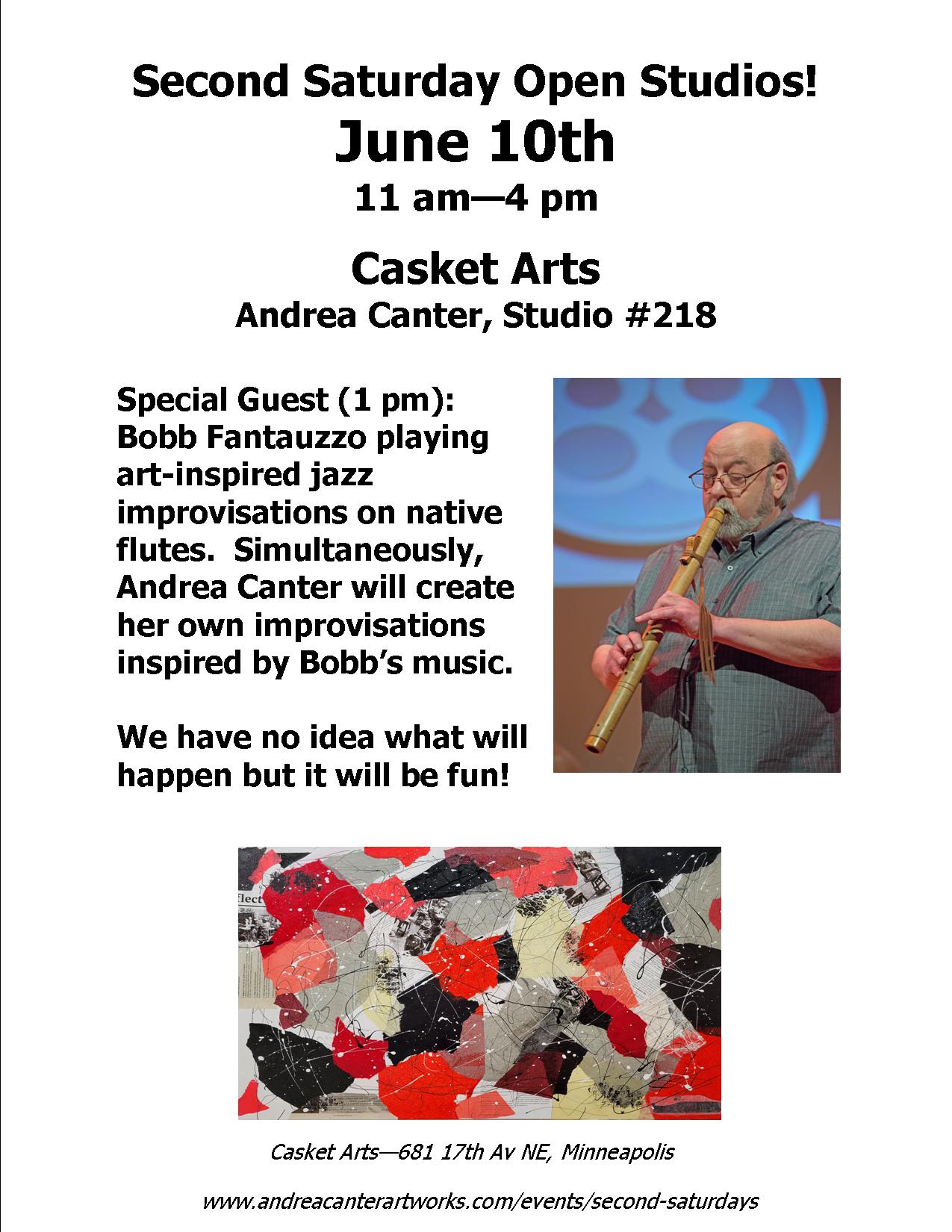

Moving seriously into art: In my late 60s, as I experimented more and more with acrylics, I realized that my home basement was inadequate as a painting studio, and sought more functional space in one of the Minneapolis art district studios. I had been sharing space for display and sale of photography and was able to move into a larger studio to support the actual work of painting. In addition to work and display space, this move also provided me with a community of artists working in all mediums. This has been invaluable in many ways, particularly having “colleagues” to share ideas and methods, as well as the opportunities to participate in “open studio” events throughout the building and throughout the Arts District, and enabling me to sell enough work to pay the rent. I can not imagine making this work if I was not already receiving my retirement income. My situation allows me to concentrate totally on the art I want to create regardless of sales, to set my own schedule, and worry (less) about critical response to my work. I do apply to juried shows, submit proposals for exhibits, and participate in a number of nonjuried exhibits as opportunities to share and promote my work. I don’t do it for a living but I do it seriously. This is not a hobby. This is my current life. And it is a business as well– using social media and more, promoting events, finding some way to bring people into the studio including those who are not likely to be major art buyers (making notecards and handpainted flower pots, hosting guest artists, etc.)

My work follows an abstract path and one portfolio (“Urban Abstraction”) might be labeled “abstract expressionist” while another strand of my work (“Imaginary Landscape”) might be labeled “contemporary impressionistic.” (Some one once told me that my work suggested the product “if Monet and Miro had a baby….”) My “urban abstraction” work combines acrylic in various forms (heavy body paint, fluid acrylics, latex housepaint, etc.), monoprinting, and collage using various papers and other materials. It can be very physical—I will drip, spatter, and throw paint as well as use knives, hard rubber “shapers,” and rarely, brushes. My other portfolio of work (“Imaginary Landscape”) also includes straight acrylic and collage approaches, is also abstract, but draws often from impressionism. My works generally range from moderate (24 x 24) to large (30 x 40, 36 x 48); the largest work I have completed so far was 48 x 60. I love working large but handling a canvas that size is really difficult at this age!

It’s very difficult to come up with a truly “unique” process given the creative range of modern artists. How we combine our individual approaches is what makes each artist unique in some way. I try to find new ways to combine materials but I am sure someone else has already tried it. Recently I have been using a clear plastic sheet material called Dur-a-lar, which I like both to just try out something since I can lay it on top of a canvas or paper to test an idea, as well as to be part of a mixed media work itself. I can glue a painted layer of Dur-a-lar on top of painted canvas or wood panel to increase the sense of depth, layering. There are more experiments I plan to try with this material.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

I think the very first thing “society” can do to support the arts is to start at the beginning–make sure art is an “ordinary” part of our culture rather than an “extra curricular” activity (in the community, in the schools). Art education should be public education starting in preschool and continuing as part of the ordinary public school curriculum through high school. At lot of preschool activities are really beginning art activities but they stop or diminish immediately. Creative teachers naturally build art activities into basic subjects but too many don’t or don’t know how. Districts cut back on arts funding rather than figure out how to build art into reading, math, social studies that doesn’t require extra funding. Of course extra funding is needed as well. Many cities have arts directors or managers– are they working with schools, with volunteers, arts educators, cultural ambassadors to bring the arts to everyone? Are there opportunities for volunteer artists to work with children and adults in the community to add art to the environment– painting murals for example. Painting city trash bins? We have to stop treating the arts (including music, dance, visual art, etc) as “extra” or “special” and incorporate art and art funding into our general lives. I am lucky to live in Minnesota where ten years ago we passed legislation to fund arts grants and projects through legislative funding (yes, tax dollars). As Keith Haring said, “Art is for Everyone.” Some of those “everyones” will have the special talent to make art their life work. And that will be a lot easier if the arts are considered normal parts of our society.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

I think noncreatives particularly have difficulty understanding/taking seriously the creatives who have turned to creative activity after or simultaneously engaging in other careers. Aren’t we just pursuing a hobby? We really are engineers, teachers, psychologists, doctors, etc who enjoy arts activities “on the side” or as a retirement hobby. It’s hard enough to be taken seriously if you really are trying to make a living as an artist, what if art appears (or really is) secondary to another career? How serious is that?

Many, maybe most of the artists I have met started out working as something else, They had careers in other fields that did not require an arts background or even any art talent. Some moved into creative arts 10-20 years into those careers or continued part time (or full time) while adding their creative arts journey. Some, like me, waited until retirement and then jumped headfirst into the world of the creative arts. The wait might have been an economic necessity. Maybe they always knew they would end up in the arts. Or maybe they only discovered their arts heart taking a casual class after retirement. It doesn’t matter. Having a second career in the arts has many benefits, perhaps mostly economic, but it’s no less serious to that artist. The difference in economics gives the later-career artist more freedom to explore and experiment, perhaps, more flexible time in the studio, perhaps more financial assets to put toward education, materials, art-related travel..,. there can be many advantages. What we don’t usually have is the years to develop our craft. I can’t look at what I am doing today and think about how I project my growth over the next 20 years– I doubt I will be able to work daily (if at all) in a studio in my 90s! It’s a shorter timeline for accomplishing goals. So yes, I am serious about my art because this will be a short career and I want to do as much as I can with it. It IS fun but I am not doing this “for fun.” There are a lot of easier (and cheaper) ways to have fun. This is what I have to do because this is how I feel complete and successful as a human. And more so than I ever did as a psychologist. But that first career allowed me this second one.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.andreacanterartworks.com

- Instagram: @andreacanterartworks

- Facebook: @andreacanter

- Other: Email: [email protected]

Image Credits

Image of Andrea Canter by Keith Miesel