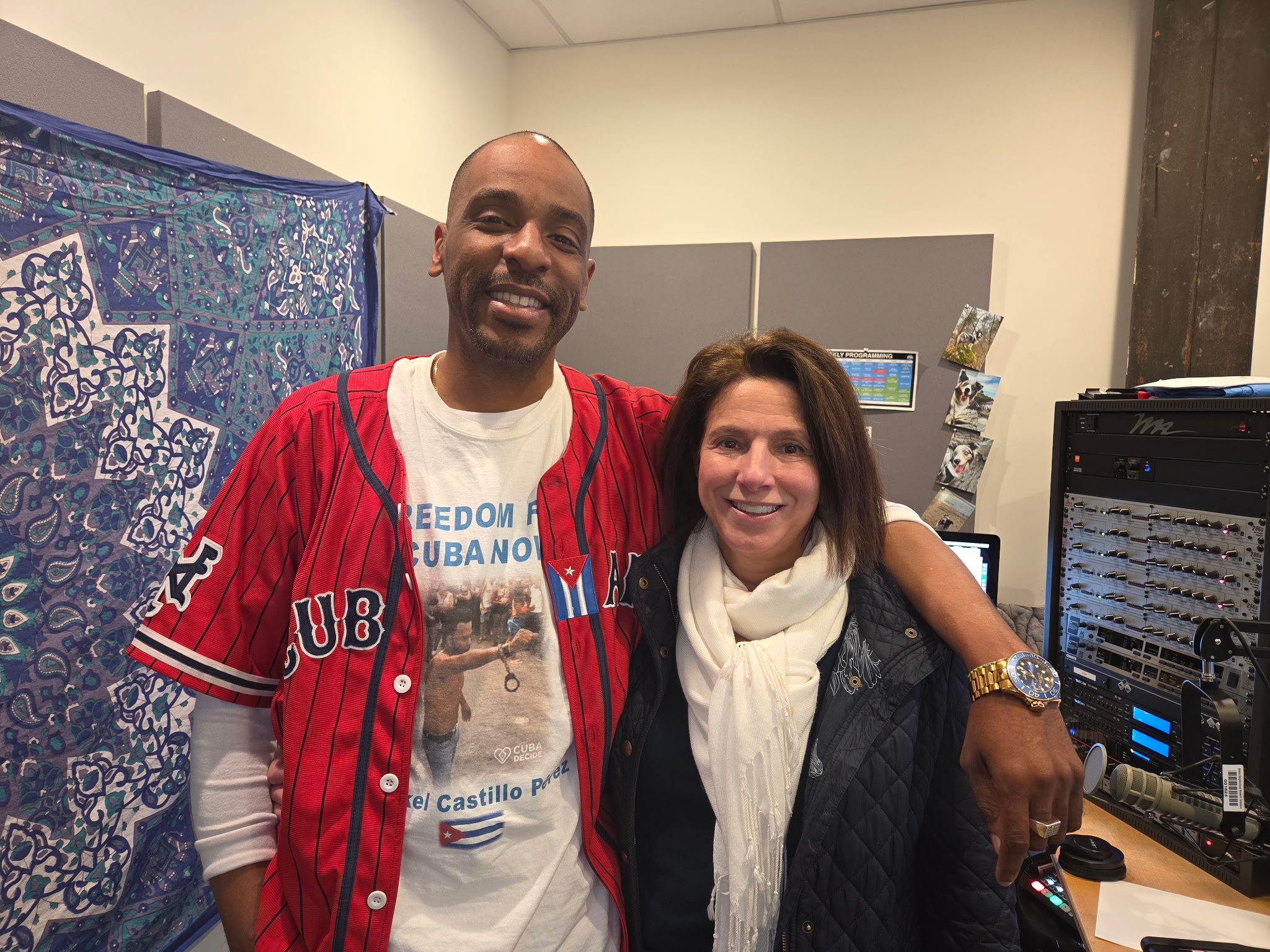

We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Ana Hebra Flaster . We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Ana below.

Ana, appreciate you joining us today. Do you think your parents have had a meaningful impact on you and your journey?

My parents showed me how to be brave, especially my mother, who led our working-class family out of Cuba eight years after the revolution she’d backed went awry. I was just shy of six at the time. My parents faced some of the hardest decisions of their lives. They’d never thought they’d have to leave their beloved barrio, where four generations of family and life-long friends lived. But the new revolutionary society and its repression forced them to do the unthinkable: flee the country. They knew they’d probably never be able to return and their families would probably never be able to get out. They hoped to get to the US, but they’d have to start again without the support of community or an understanding of the language or culture.

The process of getting out of Cuba was difficult and dangerous. They had to declare themselves enemies of the revolution and turn everything they owned over to the government in order to leave. But they did, and three years later, when they’d given up hope, a guard delivered our exit visas and kicked us out of our house. We flew to the US 48 hours later.

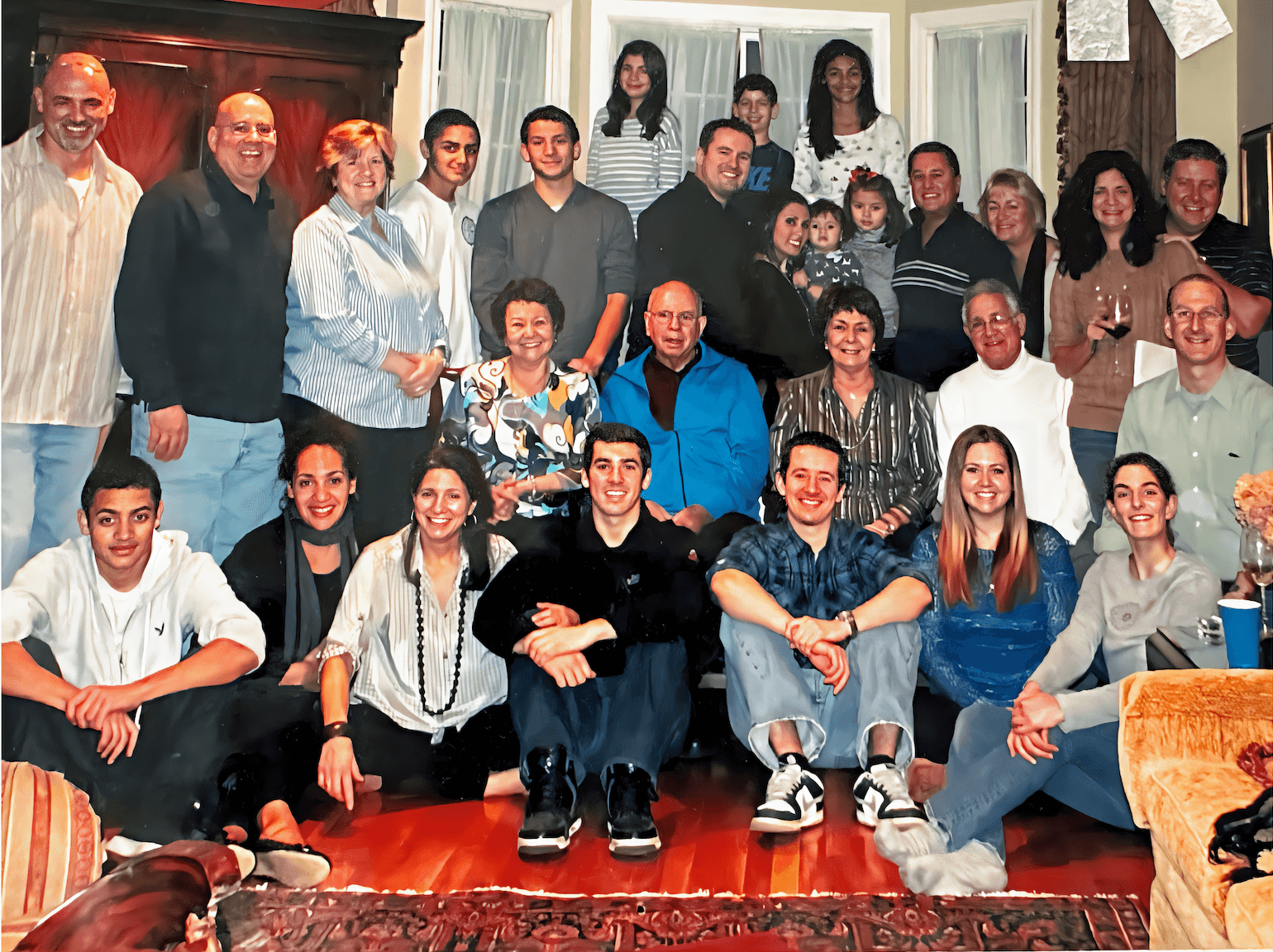

In the US, they created—unknowingly—a new origin myth for our family, one we learned subliminally as they told stories of Cuba and their youth, the barrio they’d left, the family they’d never see again. Rather than focusing on loss, they spun things around. We’d won. We’d had beaten Castro and the repressive society Cuba had turned into. We could do anything.

We needed to think of ourselves as superheroes, because other than the few other Cubans living in Nashua, New Hampshire, in 1967, we were it. We faced blizzards, the mysteries of indoor heating, a language that people seemed to speak without opening their mouths, a culture that seemed both bizarre and wonderful.

My parents worked double shifts at factory jobs along with my aunt and uncle, while our grandmother, Abuela, my mother and aunt’s mother, took care of my siblings and me, and my cousins. At first we all lived in the same rented house, then, within a few years, the two couples managed to save up enough for a small duplex, where we would grow up as we would have in Cuba, together.

The new language, culture, and climate threw challenges at them every day. They batted them back, figured things out, laughed at what they could and sorted through what they could not—together.

They protected us kids from the discrimination they encountered and the fears and doubts they had at the beginning. Would they ever see their friends and loved ones again? No, in most cases. Would their gamble—breaking apart their larger family to give their own children a chance to grow up free, with hope, and unburden by an ideology that demanded daily payment—be worth the cost? They had very little, materially. The cost of fleeing was leaving what and who they loved behind, forever.

I saw the courage of the viejos, the elders, every day. I believed I could be just like them. And I grew up being loved hard by five adults, in a safe home, even though they were grieving their losses, especially Abuela, who’d never wanted to leave Cuba and her 90-year-old father and only brother. She’d put our lives ahead of hers, and had been there to take care of us, while our parents and aunt and uncle worked.

The viejos’ steely work ethic and commitment to each other taught me the importance of family, of relationships in general. Their reliance on storytelling tuned my ear to the power of tales, the richness of each voice in the family. I became a writer because I grew up a listener, an observer. Our household ran on stories, in two languages, about two cultures.

Writing requires a type of fearlessness. You have to make yourself brave every time you face a new project, a blank screen, a pulsing curser, rejection. I saw courage in our home every day, even though I didn’t fully understand what I was sensing until later in my life. I learned that courage mattered, maybe as much as love.

The first time my mother said “ponte guapa”—make yourself brave—to me I’d fallen off my bike and was bawling on shredded knees. “Ponte guapa,” she said, looking into my eyes. I could make myself brave? I could try, at least. People around me did that every day.

I had no idea, then, how much that lesson would shape my life and my career as a writer. .

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I started my writing career after a successful career in the software field. Not surprisingly, the spark to write was related to Cuba. The Elián González controversy was in the headlines in November 1999. The six-year-old boy was the sole survivor of group of rafters that had escaped Cuba. His mother had drowned, but he’d been rescued and had been taken in by his Cuban American family in Miami. His father was now demanding he be returned to the island, where he lived. But Elián’s mother had risked her life—and her child’s—to escape the island. The father’s family in Miami said the father had at first told them to take care of the child until he could get out of Cuba. Had the regime pressured the father and forced him to change his mind? Should the child be returned to a repressive country, where people were dying as they tried to escape?

The moral dilemmas inspired me to write an essay that I pitched to the Boston NPR affiliate and later made it on the national broadcast of Morning Edition. Many other commentaries followed, often about the Cuban American experience. I began freelancing as a reporter in local papers, then magazines, and eventually in national print, broadcast, and online media.

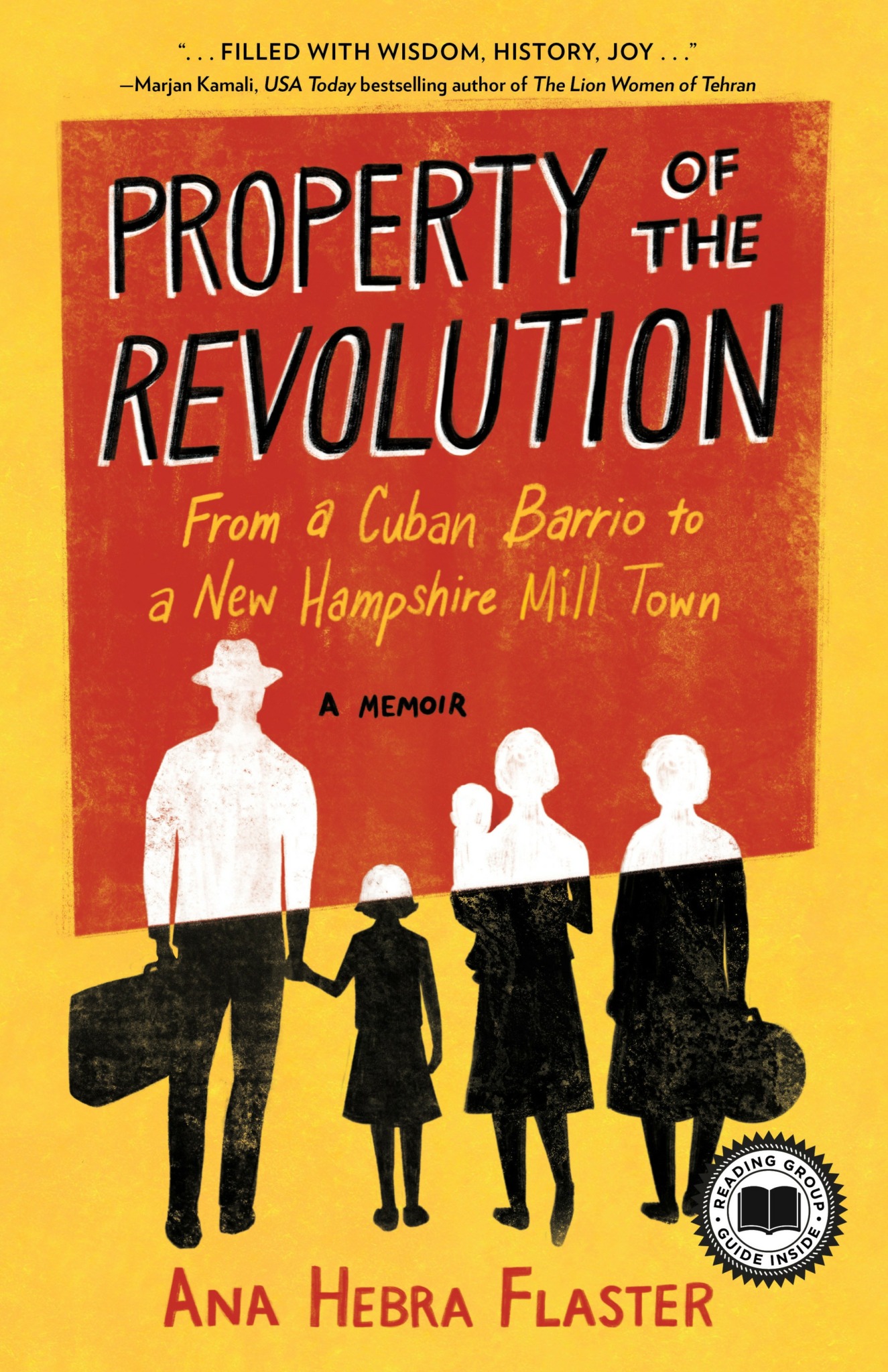

The positive reactions to my pieces on Cuba and the Cuban American experience rekindled the idea of writing a memoir about our family’s journey. I wanted to bring readers into the world of a refugee/immigrant family, the turmoil of the process, the courage required to endure and to, with luck, thrive.

I believe that understanding that—celebrating that experience—is crucial right now, regardless of where people are politically. It’s a human story, maybe the oldest human story. We are all heirs to that legacy.

If we want to better understand what’s happening in our country and around the world—we’re still in the midst of a global refugee and displaced persons crisis—we need to reconnect with that experience. I think appreciating the immigrant experience can help unite us around a shared history, maybe a few generations removed, but shared nonetheless. The immigrant experience is our country’s superpower. We need to understand it better so we can honor it more.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

Knowing that I am doing what I was meant to do. It feels that natural to me, even though I started in a totally different career. I was born to write. When I don’t write for a long period of time, I feel “off.” Something is missing. Not that I love writing, by the way. It’s painful much of the time, especially on deadline. But when the writing is flowing, time doesn’t exist, and I’m in another world. Hours can pass without my noticing. Alarms can—and have—gone off without me blinking.

I write because I cannot not write. I’m sure that sentence breaks all kinds of grammar rules, but it’s how I feel.

Here’s an example. I couldn’t know all I know about the Cuban regime’s human rights abuses, the more than 1000 known political prisoners on the island, and not investigate and share it with readers. I tried to avoid the topic. I didn’t want to cover such horrible and often hopeless stories. But the stories came for me and then I went for them. I share them every week now in CubaCurious, on Substack. Activists and prisoners’ families thank me for my work. I’m doing what I need to do and it is making a positive difference by telling untold stories that need to be heard.

As if that were not enough, writing is a landing pad for the way I notice the world—that curious, offbeat way that I think most creatives see this place. A water-strider bug moving on the surface of a lake, how does that creature stay dry? What words could capture the miracle in front of me for someone else? Look at how the sunlight reflects below its legs and breaks apart in the air . . .

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

Telling the story of Cuba and Cuban Americans and celebrating the power and resilience of immigrants.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://anacubana.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/anahebraflaster/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ana.flaster/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/anahebraflaster/

- Twitter: https://x.com/AnaHebraFlaster

- Other: https://anahflaster.substack.com

Image Credits

Jodie Andruskevich