We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Amelia Toelke a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Amelia, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about a project that you’ve worked on that’s meant a lot to you.

It is hard to remember the first months of the Covid lockdown—people were sick, dying, out of work, trapped at home balancing remote work and family life, isolated, and certainly not going out to art museums or galleries. It was during this strange and scary time that my friend, Andrea Miller, and I unexpectedly had a creative opportunity. Prior to the Pandemic, the two of us (who met in graduate school) had been working on a multifaceted project called “Worn”, that explored jewelry as vital to personal expression and a powerful tool for action, protest, and identity formation. “Worn” was sparked after we visited the Women’s Rights National Historic Park in Seneca Falls, NY, and it has grown to include artists, community members across the nation, and collaborative projects that embody different ways that jewelry can, does, and will continue to touch our lives In July of 2020, after weeks of planning and work, and with the generous support of the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, the Susan B. Anthony House, and SewGreen Rochester,

we mounted “Underpin & Overcoat” which was one facet of our project. This multi-site work displayed around the city of Rochester, NY reimagined political buttons and placed them on the architectural exteriors of buildings. Big, bold, and bright, these buttons referenced political images and slogans but without advocating specific beliefs or positions. Instead, political statement itself and the hard-won right to give voice to political ideas, was the medium and the message.

We felt it was important to include voices other than our own and so we invited local artists to design buttons. Amanda Chestnut, Tania Day, Erica Jae, Abiose Spriggs, Thievin’ Stephen, as well as the Seneca Art & Culture Center at Ganondagan all contributed designs which, like those conceived by us, were hand painted and sealed in durable fiberglass and resin.

Over the next year, in celebration of the centennial anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, we also invited participants from across the nation to reinterpret the iconic “Votes for Women” sash. This community aspect of “Worn” kicked off during a workshop held at the Rochester Contemporary Art Center, and continued via free kits that could be requested through our website and social media. Once a sash was completed it was sent back to us to be assembled as “Sash Memorial” which on view at Hobart & William Smith Colleges in February 2021 as part of the larger exhibition “Worn”. The collective effort became a monument to all of the past, present, and future efforts to sustain voting rights in the United States. “Sash Memorial” celebrates the right to vote and shows how voting remains an important tool to make this country more equitable and just. Through the recognition of individuals, “Sash Memorial” demonstrates how we are one country made of many.

The exhibition “Worn” at Hobart & William Smith Colleges was a collection of collaborative projects that was about jewelry but did not showcase any singular jewelry objects. Instead, this exhibition presented projects situated at the intersection of jewelry, social issues, and our nation’s history. Shown together as an exhibition, these collaborative artworks and projects highlighted how jewelry is ubiquitous, powerful, private, public, precious, democratic, and so much more.

Projects featured include the collaborative works Amend, Documenting the Nameplate, the Hand Medal Project, Radical Jewelry Makeover, Sash Memorial, and Underpin & Overcoat.

Amelia, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

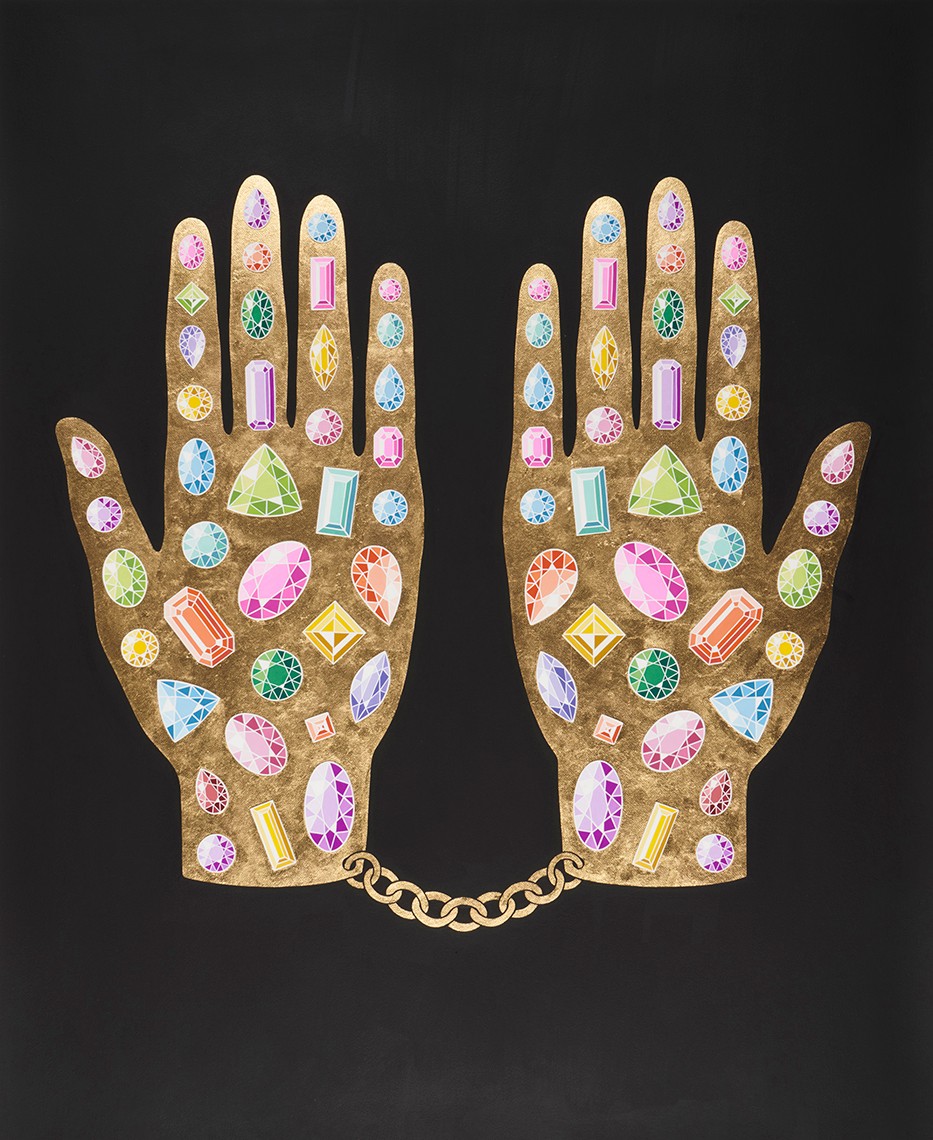

I have always been fascinated by the human need and desire to adorn and this impulse has been the backbone of my multidisciplinary practice. Through ornate works on paper using 24k gold leaf and gouache, one-of-a-kind and limited-edition jewelry, and large-scale sculpture, I continue to explore the unique and profound relationship between identity, culture, and ornament.

As a kid who always made things—from accessories for my Barbies to beaded jewelry to little pots out of the clay I dug up in the back yard—I was destined (or doomed?!) to go to art school. Coming from a small town with a bare bones art program, I had a limited view of what art was and could be. At SUNY New Paltz I took my first metals class (with the incomparable Myra Mimlitsch-Gray) and I fell in love. There was something so exciting about focusing on process and technique. It felt natural. During this time at school, I was not only being exposed to whole new field of art and art making, but I was also seeing more art in general—art that was witty, subversive, funny, and smart. I was drawn to the way metal encompasses utilitarian objects like buckets and spoons, but also ceremonial objects like reliquaries and censers, and of course, jewelry. I became aware of the way process and material and concept can work together and I began to the think about context, the site of the body, the relationship between people and things, between people and jewelry, and the inherent meanings embedded things. After graduating I spent three years working in a shared studio with friends and then decided to push and expand my work further by pursuing an MFA. I chose the three-year interdisciplinary program at UW-Madison and learned so much from working with a variety of faculty from different disciplines including (but not limited to) Lisa Gralnick, Kim Cridler, Aris Georgiades, Gail Simpson, and Paul Sacaridiz. In graduate school I found that by working across format, material, and platform—jewelry, sculpture, and drawing—allowed me to explore an idea more fully, building a more complete and complex narrative.

Jewelry, with its multifaceted social, private, and public roles cannot be easily defined—is it design, fashion, art, pure luxury? Through working multi-disciplinarily, I begin to blur the boundaries of neatly defined categories and reveal connections between disparate objects, histories, and experiences. Using the vernacular, and often cliché, language of symbols, my work is accessible by being both collective and personal. I make propositions rather than conclusions, which inspires viewers to find their own interpretations, tell their own stories, and see that adornment—of ourselves, our spaces, and our lives—is a profoundly human way that we communicate who we are.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

I feel incredibly fortunate to have an art practice. It has always been something that I can take with me wherever I go, grounding me in any environment.

It is always special to be able to connect to others through art and creativity, whether it is with other makers or with folks who choose to purchase my work and live with it—or sometimes it is both! That connection builds into community, which is especially important if one’s practice is solitary, like mine is. Having that type of supportive network is inspiring, leads to growth as an artist, and can provide comfort and advice in the low and difficult times, which inevitably occur in a competitive field and content-obsessed society.

With any creative practice or work, it is very rewarding to be able to envision something and then bring it into the world. And then when others respond to that vision and outcome, it is just thrilling. I am simultaneously grateful, heartened, and elated when someone wants to live with my work. Whether it is a piece of jewelry worn out in the world, or a framed artwork that adorns one’s walls, I feel like I have done something—albeit a very small thing—to bring some joy into the world.

I really enjoy the opportunity to make custom work, particularly when it is a piece of jewelry that repurposes or includes some part or component of another piece of jewelry. I love the way that the memories embedded in those parts will add to and gather new memories and meaning. There is a long tradition of remaking and reuse throughout the history of jewelry and carrying on this practice is a way to connect the past with the present and continue the lineage.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

I have always made it my goal to build a life that prioritizes my creative work. In an unpredictable world where humanity’s worst qualities are often on view, I hope that my work brings joy and highlights the parts of our collective and individual selves that bring meaning to life. This is perhaps a lofty aspiration, but it is one that has guided me. Beyond the art part however, I never outlined much of a career path. This means that I have had to confront and figure out the financial realities of life, often cobbling together multiple income streams. In many ways I am still figuring how I can best be financial stabile while having the time and space to create. Over the years I have taught on and off—young children, adults, and, most recently college students. Teaching has become extremely rewarding, and I am currently focusing on making it a more consistent part of my practice.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.ameliatoelke.com | www.charmstand.com

- Instagram: @ameliatoelke | @charmstand

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AmeliaToelkesCharmStand/

Image Credits

Yael Eban and Matthew Gamber Carlton Davis (myself)