We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Amelia Bartlett. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Amelia below.

Amelia, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

At the beginning of 2024, I left the investment business I’d co-founded to pursue filmmaking full-time. I’d worked the last half a year doing production on the side, seeing opportunities if I’d only had more time. My vision was to create a media production company that, rather than focusing on producing commercials for companies, would produce films, television, and documentaries that elevated regional stories and voices.

I assembled a team of co-producers, including Stephanie Hong and Kate Szekely, and we began to form a network — crucial to media production — from which we could hire crew members and cast for projects.

As with any business, this was a huge bet, not just on creative capacity but whether or not what we imagined would find a place in the market.

Amelia, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

By the time I moved from from my hometown of St. Petersburg, Florida to Knoxville, Tennessee, I was afraid I was too late to chase my dreams of moviemaking. I worried I was too old to act in roles other than ‘Mother’ and ‘Woman #3,’ a fear fed by the lack of diverse acting opportunities for women in the region. So, I did the *entrepreneurial* thing and thought, “I’ll write the roles myself!”

I began screenwriting, which ultimately taught me that if you want any say in how your script gets made, you have to become a producer, too. These self-starting tendencies could never have materialized into today’s a/b studios vision without help from mentors, peers, and my co-producers. What started as a little kid who dreamed of bringing characters to life became a collective of creative artists committed to storytelling with hearts & smarts in the places we know and love.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

“You should move to LA.” Or New York City, Atlanta, insert major metropolitan movie hub here. This seemed like the only way to have a career making movies, which may be why it took me so long to truly give it a shot.

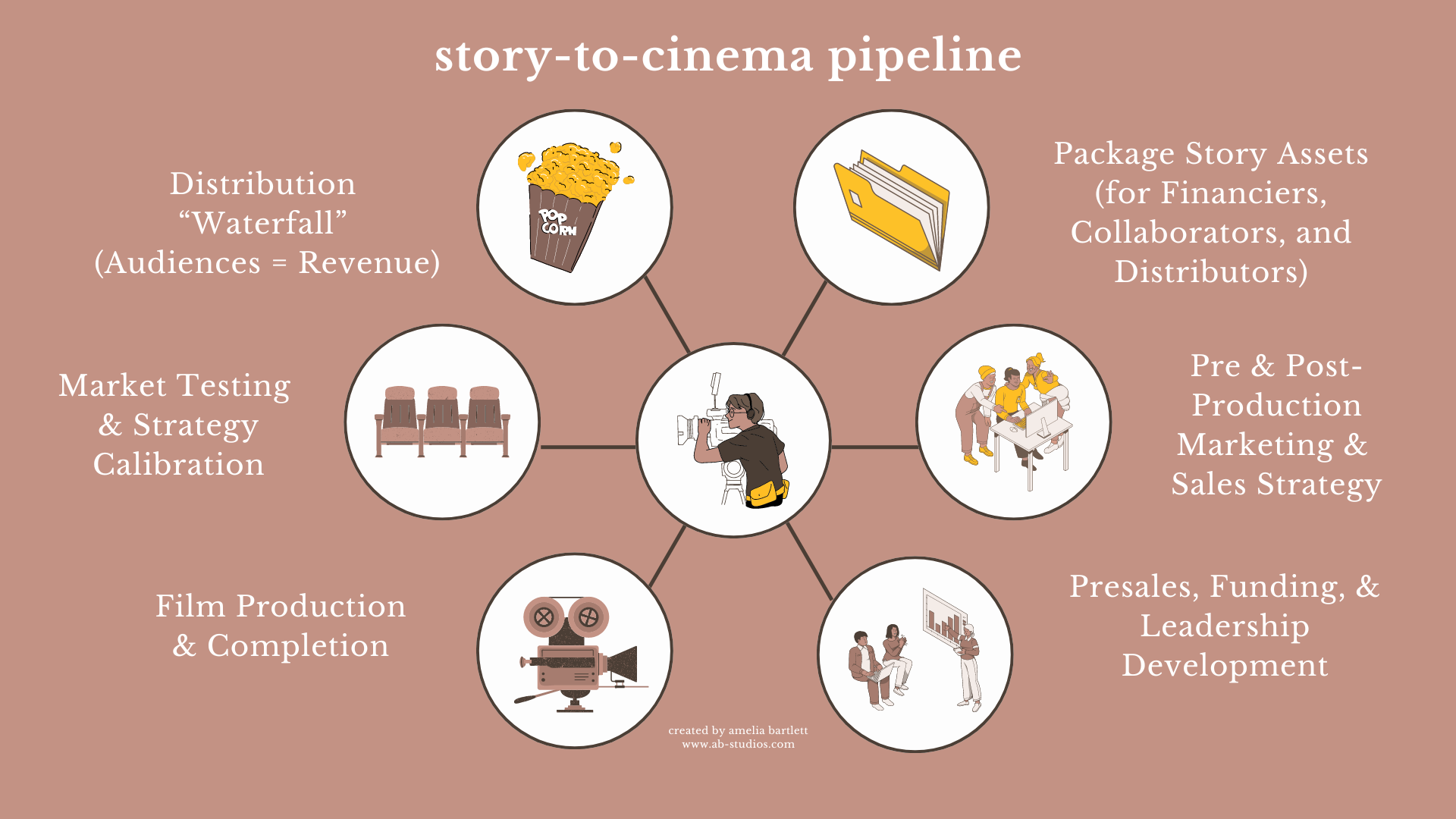

It took me almost a decade to learn that what glues the moviemaking industry together is not Hollywood or even a specific place. It’s a scaffolding, a structure of sorts that connects a truly astounding amount of people along a pathway from story to screen.

Think of it like a story-to-cinema pipeline, which includes a large concentration of individuals (who are clustered in major metropolitan markets) that make up the movie-making process. This pipeline starts development and pre-production, with multiple professionals existing primarily in this stage. In production and post-production, you have some consistent faces, but many more in a fully built-out crew. In business and marketing, you work with a lot of independent contractors (and marketing companies) that aren’t part of your company but are certainly part of your journey.

While it’s true that major markets like LA and NYC contain story-to-cinema pipelines in one place, professionals along the pathway live all over the world, and are more accessible and collaborative than ever. In-person events like film festivals, conferences, and workshops (and their virtual counterparts) offer the chance to connect with collaborators regardless of proximity — being prepared to speak to their wants and needs from your own value makes relationships possible.

If I’d have continued to believe I could only have a filmmaking career in a place like LA, it would be easy to blame the difficulties and barriers to entry along the filmmaking path simply to the lack of proximity. A cause outside my control.

Instead, I’ve grown from my dream of being a writer or actor into the vision of a full-time storyteller in the business of making movies.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

As the cost of living rises, so does the cost of creating. Beyond all the materials and places you see on screen, movies are made by people, and their time is not only valuable, but also hard-won in an always-on working society. For stories to be told at scale, from publishing to production, producers are footing a major, many-person payroll in the hopes of making a living in a fickle market.

There have always been those with abundance who see value in non-commodities like storytelling and artistry and choose to patronize projects that resonate with them. It’s a model that sort of flies in the face of capitalism. The artist is receiving money, and what are they offering in return?

Their contribution to the human conversation that is the collective of our creative expressions.

Grant programs, though often over-burdened and under-funded, are great opportunities for the creatives who qualify. And, projects with large budgets and potential to turn a profit are a great fit for investors looking to diversify their portfolio with creative equity.

But, we need more patrons. More individuals who take an interest in the arts and decide to allocate $5k – $50k per year in meaningful dispersions to creative projects they believe in. These are folks who subscribe to Patreon or contribute to a crowdfunding campaign. They are members of a community that want to see their town or team showcased on the big screen. You might be a patron, someone with money you could afford to lose but that you’d rather see feed the potential of something that moves you.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://ab-studios.co

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/ameliabartlett

- Linkedin: https://linkedin.com/in/ameliabartlett

- Other: Threads: https://www.threads.net/@ameliabartlett

Image Credits

Images 1 – 3, by Stephanie Hong

Images 4 & 5, by Michael Hutcheon

Image 6, courtesy of Joesph Moore

Image 7, Megan Allen

Image 8 (graphic), by Amelia Bartlett