We were lucky to catch up with Alysa recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alysa, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today We’d love to hear about a project that you’ve worked on that’s meant a lot to you.

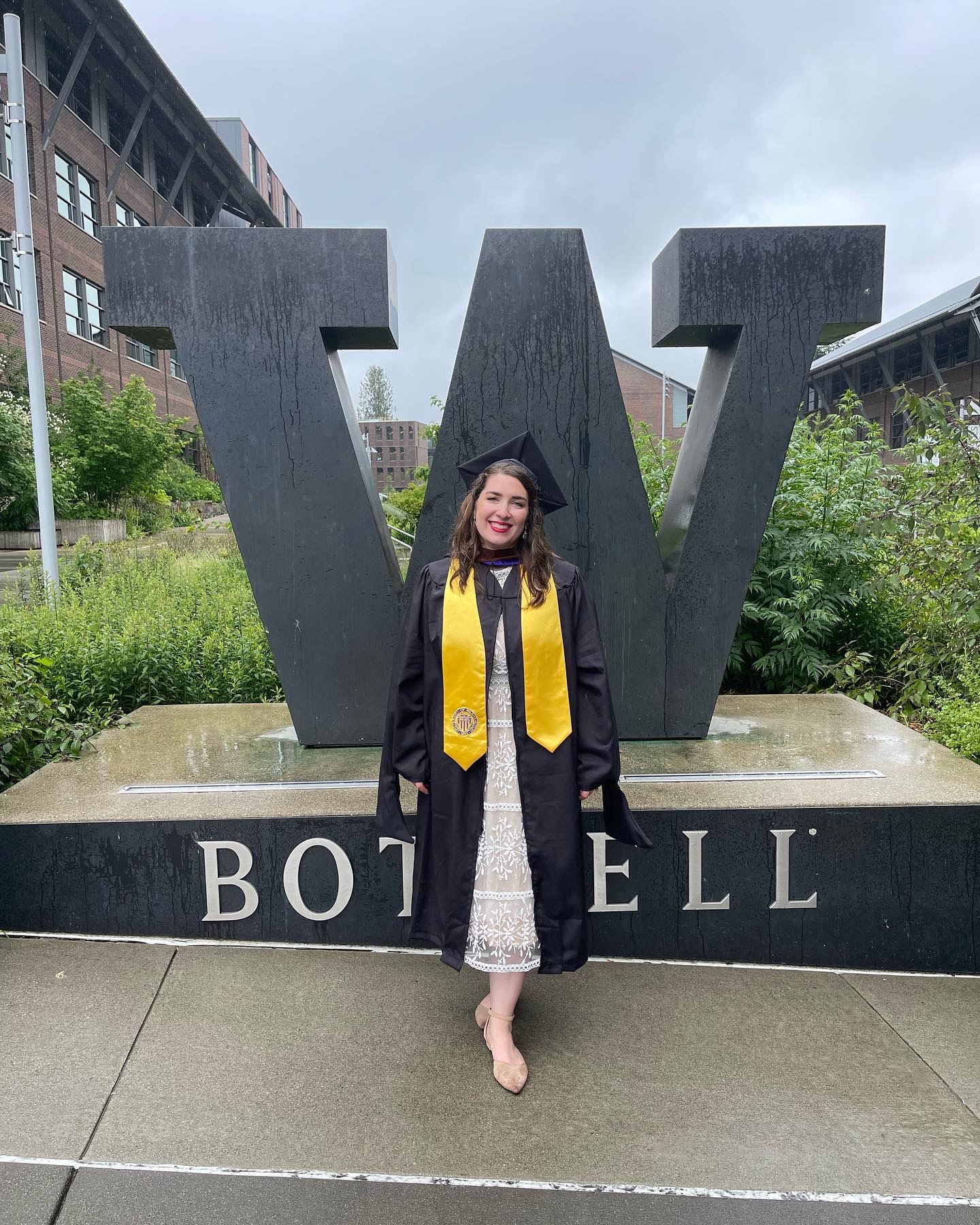

One of the meaningful projects I’ve been working on lately has been my work in progress. That’s a novel I began during my master’s program at the University of Washington Bothell. It’s called Mist Manifesto—that’s a working title, and it might change as I get to the final chapters.

I started writing it about this man, Mogyype, who is in a post-post-apocalyptic world. It’s thousands of years after some cataclysmic event, labeled as the Before Times and the Now Times. Mogyype has experienced loss—he’s a widower. One morning, he wakes up to an intense mist that rolls into town, and it’s accompanied by fog so thick he can barely see his feet. Part of the book is about trying to find time in a world where there is no concept of time anymore, since it’s not clear even when the sun rises and falls. Part of it is also about loss and grieving—when do you let go of a loss, and when do you not? When do you cling on because there’s hope, and when is your hope simply self-sabotage? Some of the story is about trying to keep your mind when nothing around you seems to make sense. Most importantly, the book is about trying not to lose yourself amidst your entire world being turned upside down.

I went through this really transformative moment in 2021. I’d been working on myself for a long time, so it didn’t start then—but I came to this really bone-chilling realization about myself and my standing in the world, and with the people I love the most, that completely changed how I saw myself. It was a violent undertaking of recategorizing everything I knew about myself—from my childhood until now. This included my relationship with my husband, my family, my friends—I had zero confidence in any of my instincts anymore. I really withdrew into myself and had to start trying to find some sort of tether or grounding mechanism in order to move forward. And for a little bit, I didn’t know what to do with myself. The only anchors I really had were my husband and writing, because nothing else seemed to make sense to me anymore.

With this current work novel, Mogyype is experiencing that, too—where the only thing that ever made sense to him was his wife, who died. He doesn’t have writing, but he has his routines. He tries to move forward every single day, with very specific meals that he eats, and the number of steps he takes into town: his routines. He slowly starts to find himself again—but even then, it’s not fully right. Something’s amiss. He doesn’t have good instincts. It’s a story I didn’t initially mean to explore. I started out writing a completely different idea for my thesis at my master’s program, but I just couldn’t get Mogyype and this haunting mist—this force that completely encases him and his life—out of my head. His story was an itch I needed to scratch, and working on this story really helped me come to terms with myself as well.

There’s also an element in the story about binging and purging. I think I have a personality that’s kind of like that too—but I mean, it’s something I see in my life and in the lives of people I care about. We don’t always know how to deal with excess and with scarcity. Sometimes when we get something we really, really want, we don’t know what to do with ourselves. We binge it to the point of hurting ourselves. I do that with TV shows all the time. Sometimes I do it with really good food—like, have you ever gotten a really good cake and just couldn’t stop eating it, even though your stomach hurts? Mogyype goes through phases like that too. And it’s been really cathartic to work on.

Alysa, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I’ve been writing since I was four years old, so writing has never really been an option for me—it’s been a necessity. Even when I was pregnant and then postpartum, when my brain wasn’t really working the way I wanted it to, one of my greatest losses was not being able to write. I felt like a part of me was missing.

I love stories. I’ve always loved stories. I feel the most connected to people when I’m telling stories and when I’m hearing theirs. I teach English because I believe that telling stories is the thing that brings us together. It’s the greatest marker of humanity that we have.

I’ve always wanted to write, but it just hasn’t really been a financial possibility for me—or, I should say, I didn’t make it a priority. Thankfully, I’ve been encouraged by so many people: Rich Zabransky in my high school, my college professors like David McGlynn, and then my husband, who has been my biggest cheerleader. He insisted that I need to commit to writing because I have something to give the world. And as soon as I got into my master’s program, it was inevitable. I think I really found my home in a writing community.

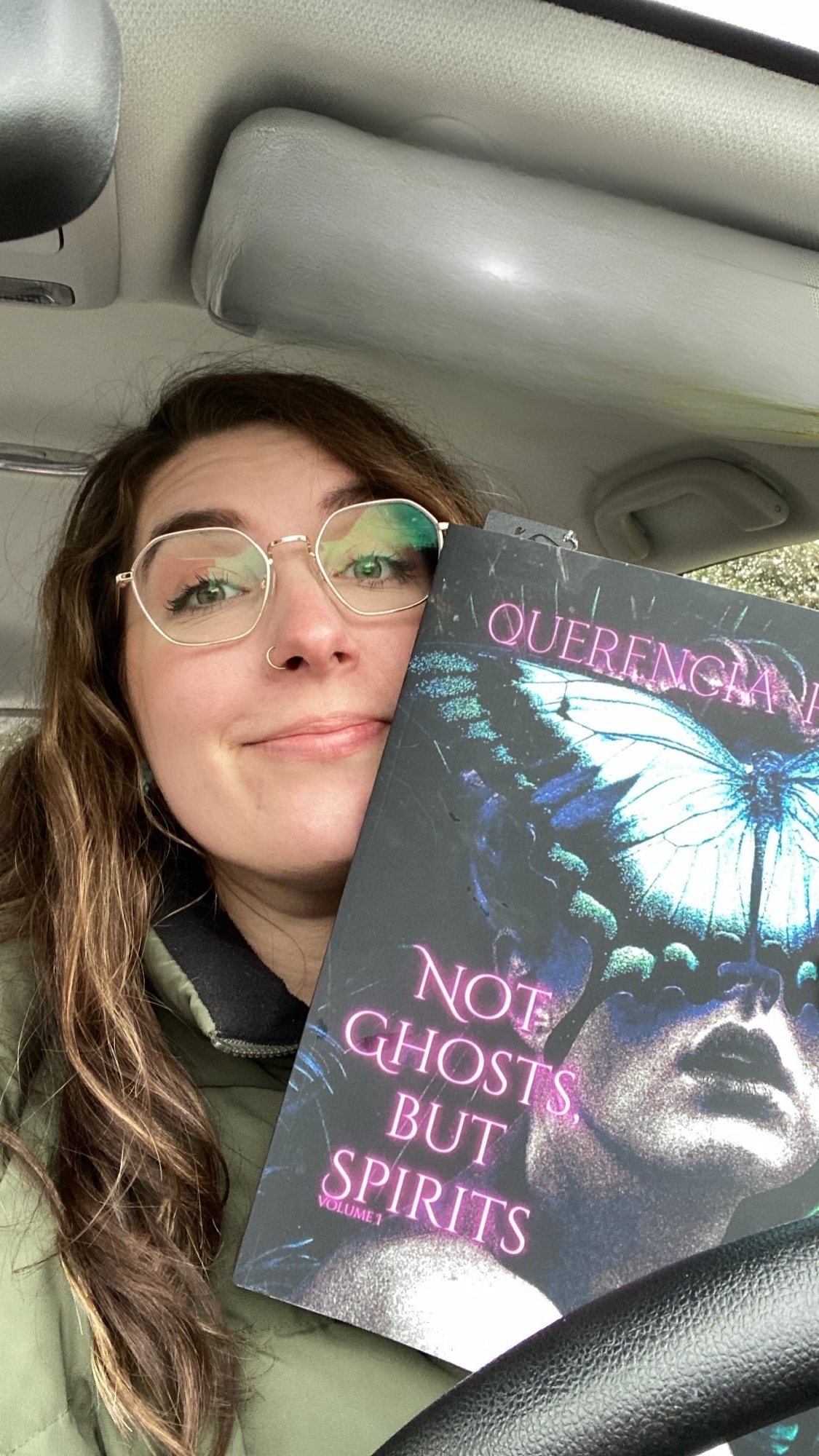

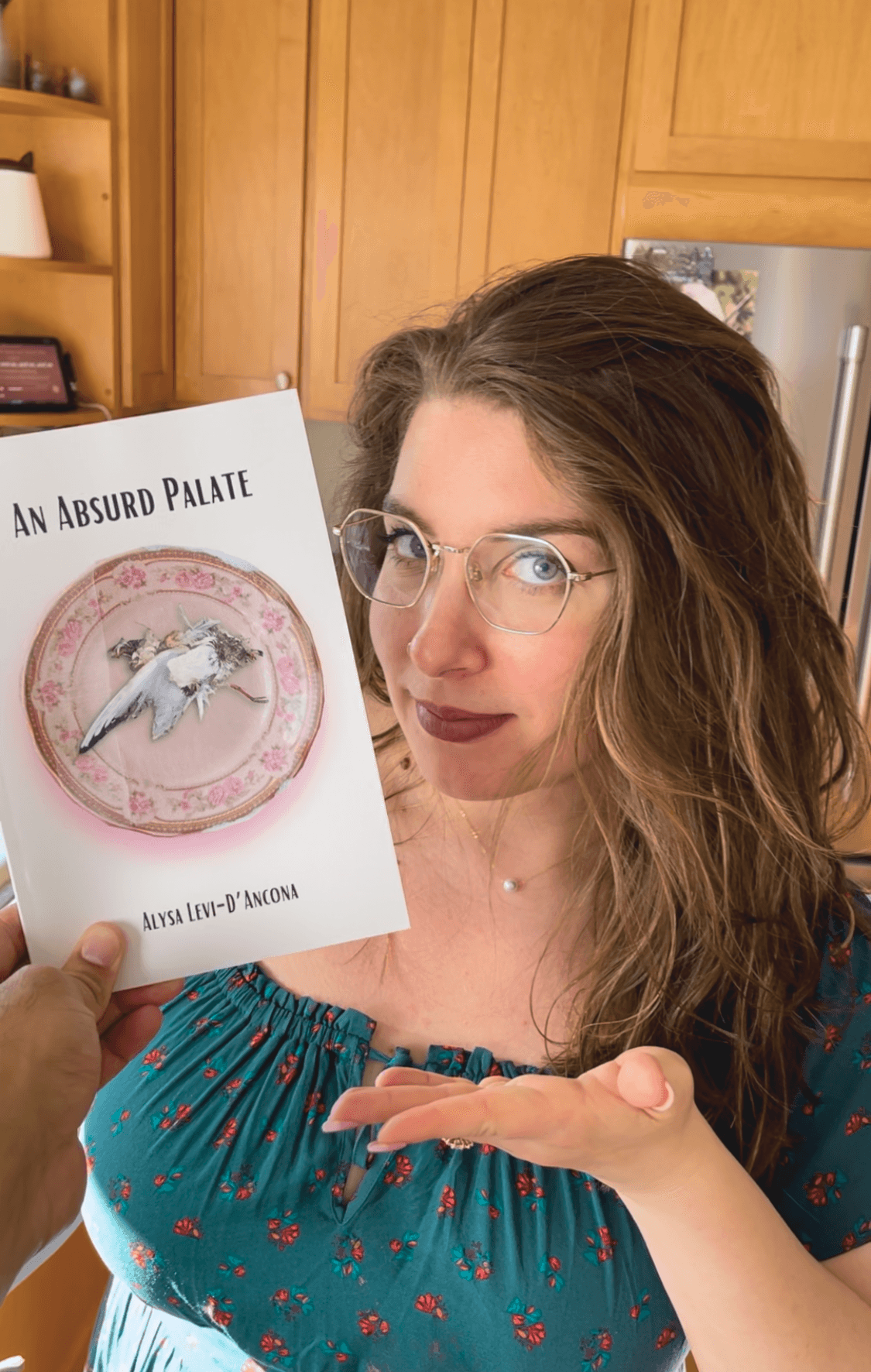

I write a little bit of everything, I think: I do poetry, I do research papers, literary analysis, I do personal essays and nonfiction. My favorite is fiction, though. I’ve write anything from realistic fiction to sci-fi/fantasy. I’ve started writing more and more stories where life is just absurd—because I think life is actually absurd quite often. My professor, Amaranth Borsuk, once gave us a prompt about creating absurdity in our stories, and I just haven’t been able to stop since she gave me permission to do that.

I love writing stories about the unexpected, any story where your expectations are completely flipped. Working with Joe Milutis helped me come to the realization that I write in a style we coined the burlesque, which branches off the idea of the carnivalesque. The idea is that a character will take some sort of performance—there’s always a performance of some kind—and use it in a way that subverts expectations and shifts power dynamics.

I think we do this all the time in real life: we socially perform for other people. But in my stories, someone is using the performance of expectation to gain power in a different way, like a burlesque dancer. Burlesque dancers are incredibly powerful—not just physically, though they are—but in the way their performance holds satire and absurdity. It’s not about sexuality; it’s about power.

You could also take the idea of someone being the “girl next door,” or someone who’s very meek. For example, I’ve written about a character who is a service industry worker—someone relatively invisible, someone others assume is stupid or unimportant. And it’s because of that invisibility that she’s able to navigate a complex world and move in ways others can’t, seeking justice in the ways she wants to. This is the premise of my short story, “The Fin of a Bird.”

I often write stories where you begin with a stereotype—an expectation of a character—and by the end of the story, that stereotype has been completely overturned. I love that. I love when I’m reading a story and the ending makes me question everything I’d read so far, especially if there’s an unreliable narrator. So, I try to create that feeling in my stories as well.

I also like writing serious stories, but lately I’ve been enjoying adding humor and silly aspects that are just fun for the sake of it. Because if I’m not having fun writing it, if I’m not enjoying thinking about these characters and the crazy lengths they’ll go to, then I can’t imagine my readers would have fun either.

One of the things I always teach my students is: there’s no story if there are no stakes. And if there are no stakes, then there’s no reason for a character to do anything at all. So I always ask myself: What do my characters want? And how are they going to get there? Glen Gers poses that in the 6 Essential Questions of storytelling as well!

Lastly, I really appreciate language. I’m someone who grew up speaking two languages. There’s something that happens to your brain when you have to think in multiple ways to say the same idea, especially with translation. And while I don’t consider myself a translator at all, I do feel blessed to know that having to think through hard concepts in multiple languages has granted me the ability to consider that there are really poetic ways to see and say important things about the world.

So, I’ve found that in my writing, not only do I want the plot to be interesting and fun, but I also really play with the words on the page. Some people might argue that I’m a little verbose and flowery, but I’d like to think I’m creating a kind of web of entertainment, although not in a nefarious way. I’m always impressed by authors who can write a sentence where there are multiple layers of meaning in every single word. It’s one of the reasons I love some poetry so much; there are so few words, but each one carries intense meaning.

I think my brain chemistry changed when I read Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, because he wrote poetically, but in a novel. And I realized I could do that too; I could write lyrically. Not in the same way as him, obviously, he has his own style I could never replicate. But I felt like I had permission to try. So now, I feel this sense of longing and romanticism in almost every sentence I write. And perhaps that’s a little self-important of me to say, but I truly believe that every sentence should matter just as much as the plot.

I strive to create a sense of intesntiy and presence in the reader as they’re consuming the words of my stories. If my character is feeling anxious, I want my sentences to feel anxious, too. I want the words themselves to build momentum, not just the plot.

I personally crave stories where the language itself is doing something more than carrying you from one point to another. Aside from Vuong, I see this in Khaled Hosseini’s Kite Runner and Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi—I can’t get that book out of my head. Patrick Rothfuss’s language is also beautiful. All of these authors write in a way that makes me stop and say, “Wow, I have never thought of [it] that way.” I hope to replicate that in all of my writing too.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I remember growing up and knowing that I wanted to write. And I remember being told, “That’s nice, but what are you going to do for money?” I’m not naïve; I’m well aware that it’s tough to be a writer in this world and also pay your bills. It’s hard to have an office job and afford a house—so yeah, you’d really have to make it big as a creative to fund a certain type of lifestyle.

Part of me is very thankful that I had someone looking out for me, making sure I had a path forward so I could feed and house myself. On the other hand, I really wish I had nourished my writing in my young adulthood. It was something I always prioritized while in school. But as soon as I got a job, I abandoned writing. It wasn’t a priority at the time. I had to work on proving myself at work. I had to work on building a community in this new place I lived. I had to work on keeping myself healthy, cooking, completing all the new tasks that come with adulthood. And I lament, to some degree, that I waited so long to make writing a priority.

More recently, I had to put writing on the back burner because I had a baby. Keeping her alive and well became my entire priority, as well as making sure that I healed, too. I don’t regret that, because I knew it was temporary. I did that to ensure that I’d have the time and the health to return to my stories eventually. But I do believe that you find time for art, creativity, and your passions if you choose to make that time.

I write in between the classes I teach. I write when my daughter is napping. I write at night, when everyone else is asleep. Because writing is a priority to me. And I wish I had learned that lesson earlier.

But part of me is also really grateful that I matured in the years between school and starting to write more seriously. If I had published anything earlier, I don’t think it would have been as introspective, mature, or impactful. I needed to do some mental growing to understand what types of stories were worth telling and how to be fair in my representations of characters and experiences.

And I will always have more growing to do. That’s the way I try to frame it: as something positive where I will be able to gain access to new types of stories.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

One of the most rewarding things about writing, for me, is the ability to connect with people through my stories. I feel such immense joy and pride in being able to create something that people want to talk about—whether it’s with me or with each other. I don’t need to be part of the conversation; I just love that people want to talk about it.

I love that I can breathe life into something, that words on a once-blank page now hold real people, personalities, and concepts. One of my good writer friends, Matt Whitehurst, tells me he still thinks about Pedsben, one of the characters from my story “Like Water to Oil.” And I think it’s because we all know a Pedsben. Thinking about him—his horrible choices, his pathetic nature—is maybe a good reminder that if we’re not careful, we can turn into a Pedsben. Harold Bloom once said that if you hate Shakespeare’s character, Cleopatra, it’s because you see yourself in her (or you see what you fear you will become), and it’s easier to express your rage at her than at yourself.

I think it’s so powerful to be able to create legacy and connection out of thin air. I don’t know if many other professions can speak to that, outside of artists. You have nothing, and then suddenly you have something. And not only is it something—it’s moving, powerful, even life-altering for some people. And I think that’s amazing.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://alysalevidancona.com

- Instagram: @alevidancona

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/alysa-levi-dancona/

Image Credits

The photos of me at panels were taken by Raelynne Woo. The photo me reading my book on a stage was by Alexandria Simmons. Everything else was me!