We recently connected with Alix Schwartz and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Alix thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. How did you learn to do what you do? Knowing what you know now, what could you have done to speed up your learning process? What skills do you think were most essential? What obstacles stood in the way of learning more?

I have always loved glass, but I never thought I would be capable of creating something with glass until I was exposed quite accidentally to fused glass, which–unlike blown glass–can easily be done in a home studio. I am fortunate to be living in the Bay Area, near one of the five Bullseye Glass Resource Centers in the US, and I started taking every class they offered, beginning with basic fusing and slumping. Before the pandemic, Bullseye would bring in renowned artists from all over the world to give in-person, hands-on intermediate and advanced classes to small groups of 8-10 learners. These classes presented an unparalleled opportunity to pick up new techniques and skills.

Glass art is a hobby for me–though it’s a full-time hobby now that I am retired. When I started I was already in my 50’s, and I would say one of my obstacles was timidity about tackling things that seemed daunting. For instance, for the first two years I never learned to program a kiln–I didn’t own one, and so I fired all my work at Bullseye, and relied on the staff there to come up with the programs for my firings. I didn’t think of myself as a technical person, and my mind would freeze up and go blank during the programming lectures that were included in almost every class. However, once I bought my first kiln, I had to learn how to program it–Bullseye does not make house calls! Similarly, the first time I took a class that included cold working (which means cutting, grinding and polishing glass artworks, mostly using pretty scary machines), I said “Oh, no. I never signed up to use power tools!” But it turns out that if you are going to make anything thicker than 6mm in glass, you do need to use power tools. Once I realized it was inevitable, I agreed to learn how to use each machine, but asked the teacher to go over each one again, more slowly, so I could take it in and use the tool safely. Nowadays I feel absolutely safe using the saw, the lap wheel and all the other tools–in fact I find the work meditative.

Art is not really worth doing unless you keep pushing yourself to try new things, and so of course I still run up against my own limitations. For instance, I do not feel I am very skilled at representational art–it seems hard to do with glass without accidentally making something cartoonish. But I keep trying to come at my stuck places from different directions, and I celebrate the breakthroughs when they occur.

Alix, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I work in fused glass, an undeniably seductive medium. Glass flows, transforms, mesmerizes the viewer. I especially like to take advantage of its transparency to create depth and/or the illusion of depth. I am not interested in working exclusively with opaque glass, because then the glass loses the advantage it has over other substances such as clay, marble or wood–but of course opaque glass has its uses in conjunction with transparent colors.

Fused glass artists start with glass in one of four or five forms: sheet glass, stringers (like spaghetti made out of glass), frit (small bits of glass), powdered glass, and billets, which are thicker chunks used mainly by artists who cast glass (which I do not do). We transform these raw materials into everything you see on our websites and in our open studio sales. Glass is an incredibly versatile material, and I don’t like to limit myself to using it in only a few ways. These are a couple of the ways I most enjoy making things with glass:

Pattern bars: this technique combines serendipity and symmetry in ways that surprise and delight the eye. I start by melting strips of glass (all the same length, but different widths) together into a block or wedge, being sure to leave negative space for the glass to melt into. Once that block or wedge is cool and cleaned, I slice it up so that each slice is identical. (The moment the first slice comes off the saw is so exciting and surprising!) I then arrange the slices until I find a pattern that appeals to me, and then dam those pieces together and fuse them in the kiln, After cold working the edges I slump the piece, which means I put it back in the kiln on top of a mold that it can relax into. Examples of this technique are my “River Runs Through It” piece and the “Arrowheads” round platter.

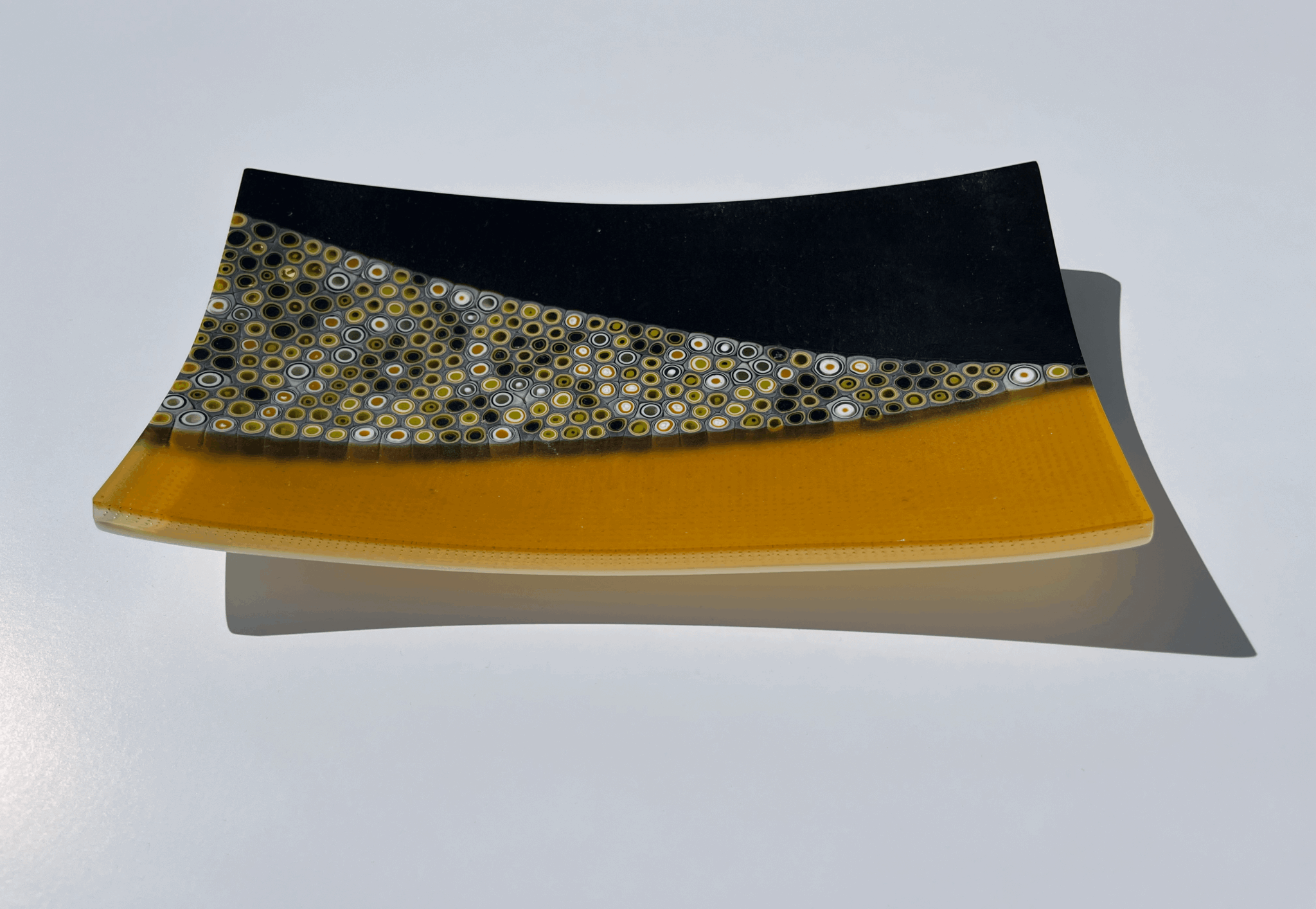

Murrine: Artists in Venice have been making murrine for centuries, but Bullseye created a new technique for making murrine in the home. I use a vitrigraph kiln to make my own murrine. I start by cutting circles out of sheet glass, and placing them inside a regular clay flower pot with a hole in the bottom. I place that in the vitrigraph kiln, which is a small overhead kiln that also has a hole in the bottom. When the glass is hot enough (around 1520 degrees) it starts to bulge out of the hole. At that point I use a pair of pliers to grasp the bulging glass and start pulling the molten material slowly out of the pot. This process results in long canes, which, when cool, can be snipped up into short lengths to incorporate into artworks. My “Homage to Klimt” is one such piece.

Until recently I have made mainly useful objects, such as platters, vases, and bowls. I am now moving into a stage where I want to focus more on art that is less functional. I have been working on abstract pieces, minimalist pieces, and some landscapes (which are often either abstract or minimalist as well).

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

I come from a family of very creative people, but for most of my life I did not count myself as one of the creatives! We had a family tradition of getting together over the holidays and making crafts for days on end. If you praised something someone was making, you had better really like it, because they would probably wrap it up in holiday paper and put your name on it! Everyone was making beautiful objects, but everything I tried to make came out looking very childish, and that is an unintended insult to children. I would usually throw in the towel after a few hours and go into the kitchen to make dinner for everyone, exclaiming that cooking was my art!

I was in my fifties before I discovered the art form that I was actually good at: fused glass. Glass was the right medium for me because I love it: it inspires me and I love looking at it, manipulating it, playing with it . . . .everything about it. It was also right for me because it’s forgiving. If you are not perfectly precise, the glass will melt together and make your small errors disappear–at least up to a point. The first time I made a simple glass plate, I had that magical feeling: “Hey, I can do this!” I wanted to do it more and more–and so I did, gradually building my skills and knowledge over the next 15+ years.

So my recommendation to anyone reading is this: never decide once and for all that you are not creative. It’s possible you just have not yet found your medium.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

The lesson I had to unlearn was something that I had taught myself, when I was just in high school. I loved to make art back then, but when my art teacher invited me to participate in an after-school oil-painting group, none of the paintings I made looked remotely like the paintings in my mind, the paintings I intended to make. So I told myself that I was not a good painter. . . .not an artist after all. And I quit.

Most adults can probably spot my error here. NO ONE is a good painter when they first start out. Painting, like any other skill, takes practice to become good at. I taught writing for many years at the university, and I would always show my students first drafts of stories by prominent authors, to prove that even the best writers do not just sit down and write a masterpiece. It takes years for them to get any good at it, and even once they are good they have to keep working at their craft, writing and re-writing again and again until they produce the polished masterpiece that their publisher accepts. Why should oil painting, or fused glass, be any different?

Contact Info:

- Website: https://alixschwartzglass.com

- Instagram: alixschwartzglass