Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Adam Hinkelman. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Adam, appreciate you joining us today. When did you first know you wanted to pursue a creative/artistic path professionally?

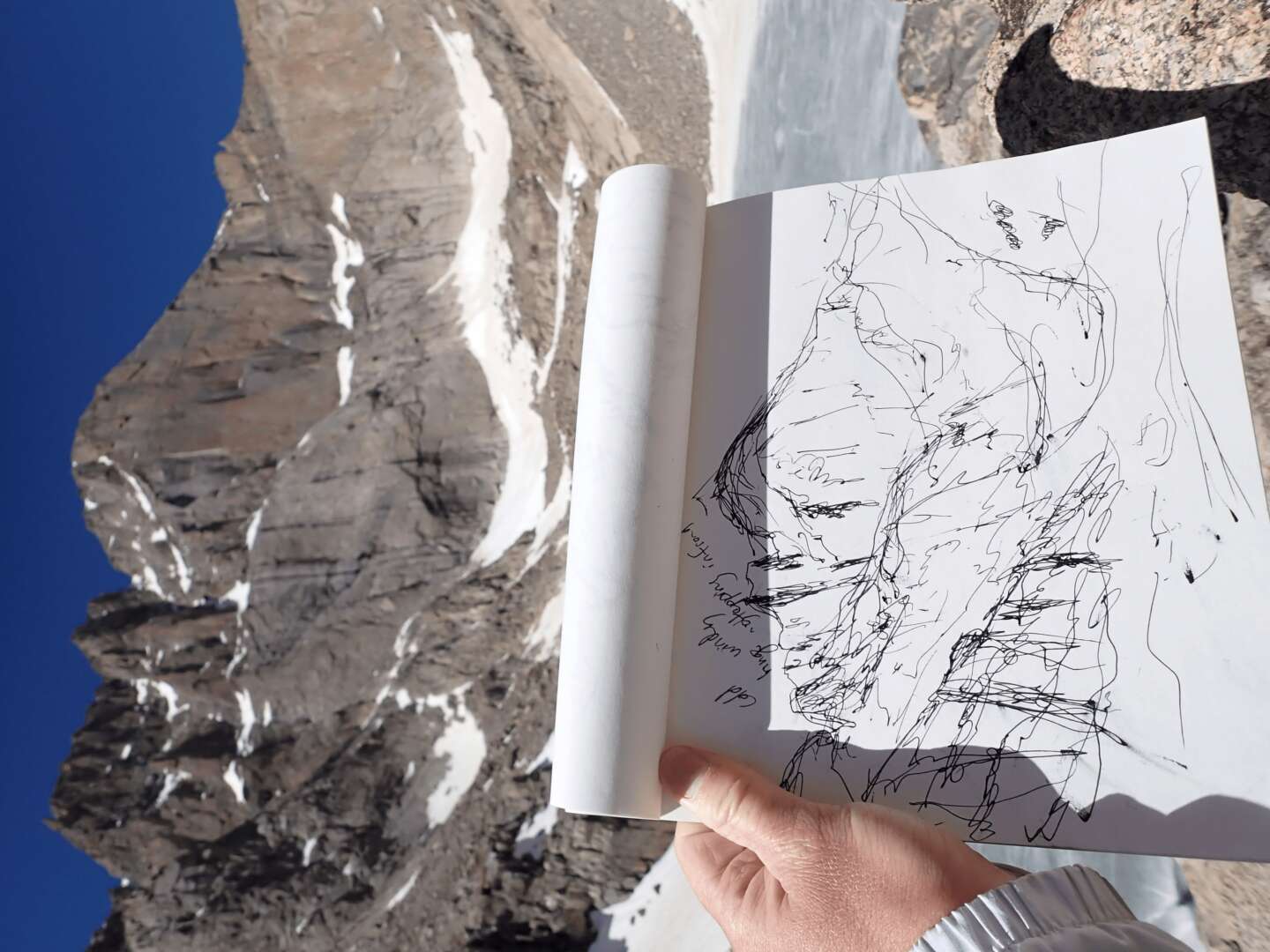

While the idea of pursuing a career in the arts was seeded in my mind at an early age, it did not become a reality until my early 30’s. For a decade, I developed outdoor industry experience while painting and commissioning works on the side. There was never a singular moment that initiated my shift to the arts, but rather many which coalesced to giving me the confidence to change my primary career trajectory to become an artist and art educator. From supportive people and continuing the development of my art practice with an MFA program to the important ingredient of ultra distance running, many experiences complemented my professional drive to become an artist. However, if I were to choose a time, I knew I needed to pursue a creative path after a summer of high mileage outings biking and running to areas I wished to paint. The time spent riding plus running to altitudes of thirteen thousand feet spurred thoughts on the human perception of time and space in relation to mountains and forests. From these experiences, phrases like “a mountain is only a slow wave” by photographer Judith Stenneken reverberated in my mind, inspiring my desire to paint.

Adam, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

First and foremost, I am a landscape painter who evokes agency of ecological subject matter. The term “agency” is complex, but from my perspective, it represents how all things big and small act on their own accord and interact with other agents. By acknowledging agency of non-human organisms, my paintings aid sustainability perspectives by encouraging empathy towards nature and offering a sympathetic response to the complex natural system relationships around us.

As an artist, I have been selling commissioned works since I was eighteen and now at thirty-three my artwork has evolved as well as my desire to teach. I am heavily influenced by the mountains and nature growing up in Boulder, Colorado. From a young age, my parents and grandparents taught me about landscape’s complex relationships among ecosystems, geology, and human interaction, working as a naturalist, city planner, and physicist/meteorologist. During my undergraduate years, I studied marketing and fine art at a liberal arts college and played Division II soccer. I then worked in the outdoor industry for roughly a decade and continued painting on the side. In 2021, I decided to recenter my focus and pursue a career in the arts full time. In 2024, I graduated with my MFA from Colorado State University. My work has been shown in a variety of academic and professional settings, most recently at the Gregory Allicar Museum and the UN Climate Conference in Dubai for my tree portraits. Currently, I am an independent professional artist living in Vermont and am an aspiring professor.

As mentioned earlier, a significant contributor to my practice has been ultra trail running. I use trail running as an essential part of my process to explore movement across, over, and through various landscapes. From the trail’s surface to weather, elevation gain, flora, fauna, and more – many physical senses influence the result of my paintings. These physical sensations are heightened to a more extreme degree after running ultra-distance trail races, including the Leadville 100-mile race through the high mountains of Colorado. As many runners I know have also experienced, running 100 miles alters one’s perception of time and space, abstracting landscapes in an almost time dilation effect and changing one’s perceived relationship with the physical world. Sometimes these running experiences translate to a pause, as seen in my tree portraits, inspired from my running in the dark with only a headlamp to illuminate the trunks of trees.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

Artists can be supported in a variety of ways, whether attending galley openings, museum exhibitions, or purchasing of art. Beyond the surface, society can support artists by being open and willing to digest new concepts and ideas in the art conversation. Some works resemble an iceberg where the aesthetics and meaning are far below surface. It’s helpful to support a healthy creative ecosystem where spectators offer curiosity and problem solving when they might not understand a work of art initially. Recognizing the context of artworks is important to understanding new philosophies and aesthetics in the world.

Additionally, fostering a supportive atmosphere for developing artists is essential. Whether municipal opportunities, private grants, or artist residency options, it is crucial to provide resources for aspiring artists. This not only includes financial support for material and equipment and studio spaces for creating works, but also community opportunities to discuss and critique a diverse body of work in welcoming atmospheres.

Lastly, I personally believe in the value of multidisciplinary collaborations to enable the cross pollination of ideas and perspectives. Whether with academic, municipal, or private settings, offering artists the ability to collaborate and extend ones reach in their discipline is important. For my art practice, collaborating with the sciences allows me to exchange ideas and perspectives in order to create influential works and learn more about my subject.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

The goal for my work is to deliver paintings that accentuates nature’s agency among uniquely complex ecological networks to aid environmental sustainability and social equity. In many of my paintings, I try to express the energy and movement that is present in landscapes and with organisms that are often depicted as static. From an art history context, the formulaic representations of old western landscape paintings adopt the perspective known as the “colonial gaze” through imagery offering expanses of soon-to-be cultivated land inhabited by indigenous Americans, who were later systematically and tragically removed from their homelands. To encourage belonging among diverse peoples and support sustainability, I attempt to make paintings that adopt a decolonial perspective and offer non-anthropocentric viewpoints, supporting healthy relationships between humans and natural ecosystems.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.adamhinkelman.com

- Instagram: @adamhinkelman

Image Credits

NA