Today we’d like to introduce you to Nathan Cole

Nathan, we appreciate you taking the time to share your story with us today. Where does your story begin?

As a child, I was fascinated with wildlife. I would watch them in nature, draw them, and read everything I could about them. I even read a two-volume encyclopedia of mammals out of my own interest. So I knew from a very young age I wanted to be a wildlife park ranger or an environmental artist.

When it came time to go to post-secondary school, I chose the fine art route with the goal of becoming an artist as a career. College and university are incredible in that you learn critical thinking, tackle huge projects, study a wide variety of subjects about the world, and have a chance to find out who you are as a person and what brings you happiness. However, one drawback is it doesn’t always prepare a path for you to apply these ideas and accomplishments for existing in a capitalistic society.

When I came out of art school, I lacked knowledge or connections on how to jump right into being a full-time artist. Soon enough, your basic needs as a human come into play and you have to find work. Unfortunately, work in this society is almost designed to leave you so tired that all you can do is maintain yourself and the people around you, rather than seek more. As time passes, the knowledge and connections of the art world become even more sparse and the dream can fade in and out a little.

Strangely enough, it was a massive battle with my mental health that finally gave me the time and space to reconsider my options (covered more in a previous interview – https://boldjourney.com/news/meet-nathan-cole/). I had to take a medical leave from my work due to depression and anxiety, and while that is not an ideal time to consider my future, it made me slowly realize I couldn’t continue to live the same way without endangering myself further. After trying and failing once to return to work, I made the hard choice to pursue my dream. I knew I had a bit of savings to work with, but without more income coming in, I had to do a lot of creating and learning, fast. This was tricky as I was still battling anxiety and depression, I would only have a decent couple of hours a day where I had the focus and energy to do something ‘productive’.

So, lacking mentors or colleagues in the art business, I had to teach myself what I could and learn from other available sources bit by bit. So I studied the application process, created a consistent body of work, assembled a CV, and composed info about my art and myself. I attended workshops, watched seminars, joined professional groups, and learned from my successes and failures. I got used to rejection (as that will happen no matter what), but started enjoying new and unique successes as my CV expanded with them. I learned about artist residencies and attended my first one in Costa Rica, which was an immensely engaging and creative time for me (I talk more about the residencies here – https://boldjourney.com/news/meet-nathan-cole/).

Now in my fifth year as a professional artist, the challenges are ongoing, but so are the new and exciting opportunities and successes. I am working to share my experience in the administrative side of art by mentoring other emerging artists. Perhaps, one day, I could even run a centre dedicated to that purpose. I have returned to oil painting, a medium I focused on in school, which has re-opened new possibilities of expression. I have begun experimenting with wood carving and other sculptural mediums as a beginning step into the public art field. This is with the goal in mind of eventually creating medium to large three-dimensional pieces that could sit at the entrance to a museum or decorate a public park. With this new freedom in material expression, the concepts and ideas behind my work have also expanded, tackling new environmental subjects such as the effect of military sonar on marine mammals or the nutrient cycle of whales.

Can you talk to us a bit about the challenges and lessons you’ve learned along the way. Looking back would you say it’s been easy or smooth in retrospect?

The biggest obstacle to building my art career, or working on anything for that matter, has been my mental health. I usually only have a few decent hours in a day where I can be productive to some extent, which can be frustrating and slow. When you add in the unpredictable nature of the art journey, things can get even trickier. There is progression, then regression. You must be used to rejection, yet maintain a positive outlook so you don’t show desperation or cynicism in front of potential supporters, as that doesn’t make you approachable. In many jobs, even on off days where you don’t have a productive day, (in many cases) you know you will still get paid. There is no such security blanket with art, no matter what you do that week, there is a chance you won’t make any money. Much of the work is done in prep or applying to things, without knowing if you will be paid. On top of that, many applications require you to pay or you have to invest in your work before even showing it.

As with all careers, certain things can be out of your control. For me, I had been pursuing art professionally for a year, building solid momentum in my art practice when the COVID pandemic hit. This business impact was echoed across the cultural, tourist, hospitality and other industries, often combined with the rising cost of living in cities. Much of the support systems and opportunities in the art world require you to not only attend events in the city but also be an official resident. I returned from India on my second artist residency just a week before the first shutdown happened. That meant that opportunities to sell my art and learn dried up, residencies, exhibitions, workshops and more either shut down or went online (which isn’t a good venue for everyone) and overall public spending changed or slowed.

Finally, being an artist requires you to switch between aspects of your brain and personality consistently, some of which may be far better developed than others. On any given day, you have to be a creative producer of work, a writer and editor for applications, a marketer of your pieces and yourself, a manager of financial budgets and cost/benefit analysis of opportunities, a networker for collaborations and letters of recommendation, and finally a highly self-motivated individual, as much of the work is done by yourself in isolation.

Some may wonder why I would want to be an artist if the lifestyle can be so precarious. Or maybe others would wonder if myself or others aren’t good enough to succeed, or even think maybe artists aren’t a necessary or ‘real’ profession. But I feel compelled to create, to put something out there that brings thoughts, feelings, or beauty to the world. I have seen people find success in the cultural fields, and I know I could get there as well, it just takes ideas, practice, an arts infrastructure, and maybe a fair bit of luck. I know that despite these obstacles and setbacks, this is the most fulfilling work I have done in my life. The feeling you get after creating a piece that surprises even yourself is magnificent. The opportunity to see people’s faces light up and fill with curiousity when they view your work for the first time. To captivate people with stories of travel adventures and encounters with fascinating animals. All of this fills me with purpose, motivation, and joy, and if you read the first part of my story, those three things are exactly what I (and likely many others) need right now.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar what can you tell them about what you do?

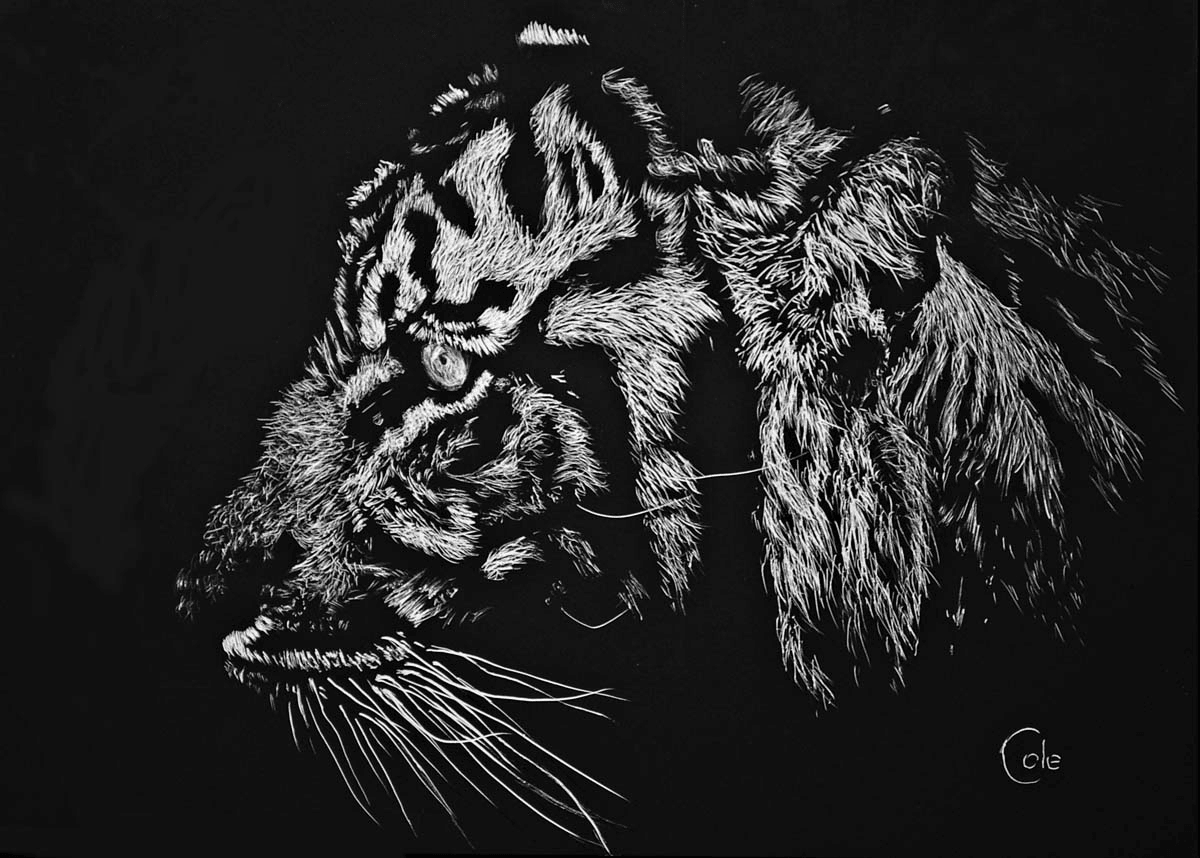

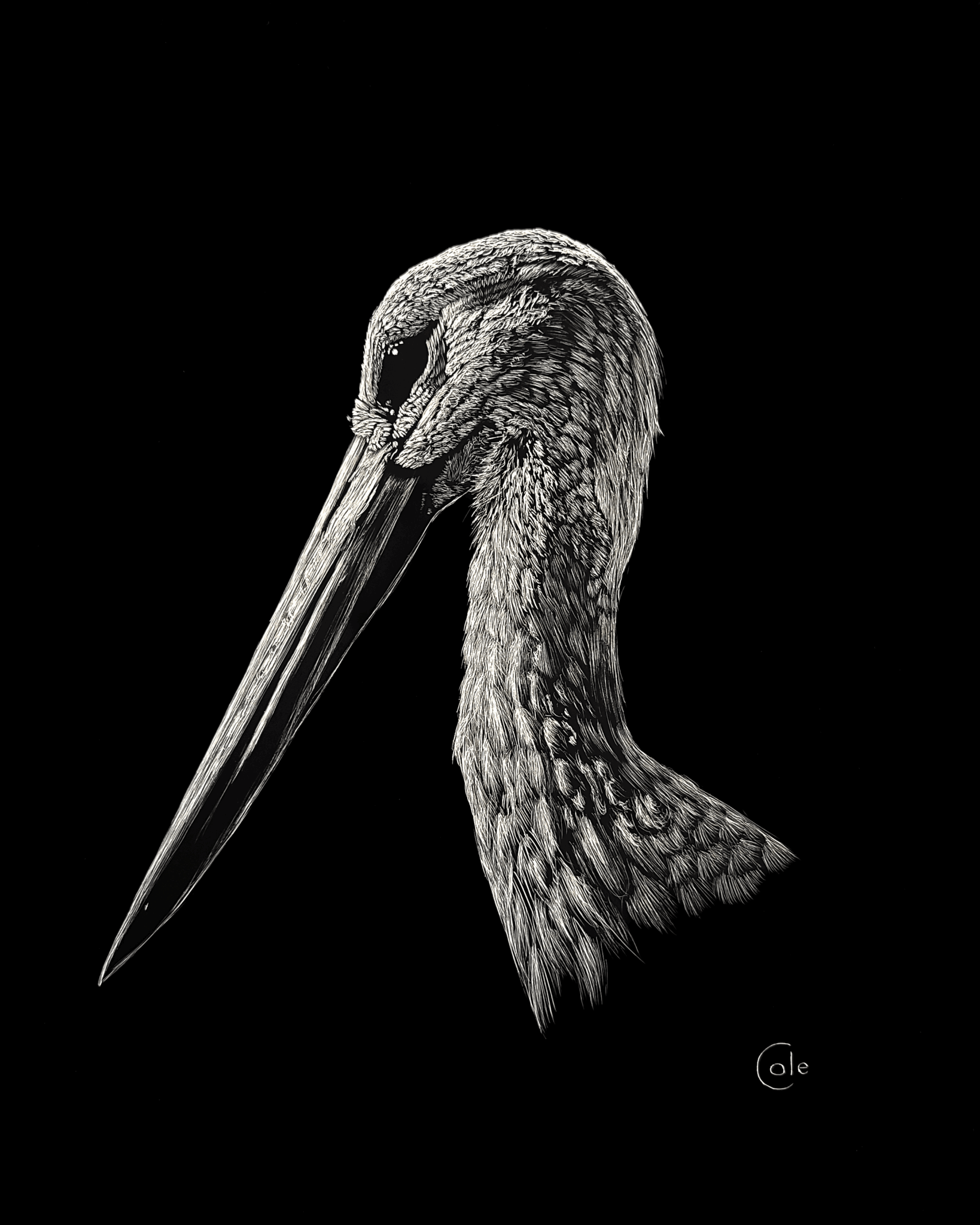

My primary medium as a professional artist has been scratchboard. As it is a lesser known medium, scratchboard is a masonite board covered in a white clay middle layer and covered black with ink. The images are created by using a metal quill to scratch away the black so that the white appears underneath. Texture, depth, and shadow are created by varying the pressure on the quill, the angle it is used, and repetition on the same spot. It is a painstaking process that can be difficult to plan out ahead of time. So each image is built out slowly from a focal point, keeping the proportion in my head the whole time. Each work, depending on textures, size, and complexity, can take from twenty to fifty hours, spread out over a period of time as each session takes all of my focus and energy.

I am also a wildlife photographer, which started as an effort to source my own reference images for my scratchboard, but has evolved into my own citizen science/naturalist project. As mentioned above, I have also returned to oil painting, and begun experimenting with sculptural materials such as wood carving.

When I create artwork, I do so with an eye on how nature, and the wildlife and ecosystems that are part of it, are currently perceived. How did the historical culture of an area play a role in these public viewpoints? Did the culture create myths, misconceptions, desirability, or fear? Were they viewed as a resource to be exploited, a pest to be persecuted, a curiosity to be collected, an inconsequential nothing to be ignored, or a danger to be exterminated? I keep this awareness in mind when I create, knowing that the stories we tell can have a far-ranging effect on the livelihood of a species.

Another consideration when creating is whether it is possible to use art to rebuild natural connections mentally and physically. Can our experiences with culture motivate us to connect isolated bits of natural areas in the physical world, and in turn bring us closer to a new understanding and relationship with nature? In a large-scale infrastructure sense, can we create a connected network of green spaces and ecosystems to each other to ease natural migration and movement patterns for species? Can we find ways to remove dangerous impediments to species movement so we can witness these healthy ecosystems around us? To view natural and healthy patterns rather than a series of roadkill or fatal window strikes or the myriad of other ways that animals can fall victim to our creations? This would create a physically healthier environment for us to live in, and a more positive mental space for us to inhabit. By exploring the pathways through these green spaces, perhaps we could incorporate some of what we feel and learn into ourselves. Studies have shown that being in nature can provide a sense of peacefulness, balance, and joy which provides mental opposition to the consumption, grind, and internal strife of the capitalistic world. As we rewild the spaces around us, we would, in a sense, be rewilding our minds.

To convey all of this above through each piece of art is an impossible task, so I take it one idea or species at a time, working to create an experience for the viewer where these thoughts or discussions could take place. When possible, such as during an artist talk at an opening, I do my best to share my perspectives and experiences in nature. Yet, it is also up to the viewer how they interpret and react to the pieces in front of them. After all, each person arrives with their own lens in how they view the world, and only with this awareness of the myriad of perspectives can we work towards a respectful and cooperative relationship with nature.

In terms of your work and the industry, what are some of the changes you are expecting to see over the next five to ten years?

The continued expansion of AI technologies into creative and cultural fields will be an adjustment for everyone involved. For instance, how will awards and grants react to AI art in their applications? Are experts needed to consult organizations on things to watch out for or how to set standards or guidelines for submission practices? I believe we are likely to see both a backlash to digital technologies with a wave of tactile art with natural components, and a section of the industry embracing it. Beyond the practical component of the use of AI in cultural fields, there are also the creative, financial, and environmental costs. In a world that is under a deceptive information onslaught, the need for critical thinking is at an all-time high. Over time, writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians and other cultural producers have helped us interpret and make sense of the world we are in, but in the current financial landscape, it is harder than ever for them to have the necessary security to create. AI relies on current creative works by real people to pull from to generate its product, what happens when there is less and less new and relevant work and it is just pulling from itself? If you thought waves of movie sequels were bad, or that new music all sounds the same – just wait until AI starts cannibalizing itself for content.

Finally, maintaining and running AI programs isn’t without costs, financially or environmentally. Scanning the internet and generating this content that is an amalgamation of bits and pieces takes massive processing power, which in turn has gigantic energy requirements. They have to create huge expensive properties of computers, which they call server farms, to process all this data. These not only suck in vast amounts of electricity, but they generate a nightmare of physical and mental symptoms for nearby populations due to constant sound and vibrations. These need for server farms and their massive side effects are a commonality they share with all Blockchain technologies, such as Bitcoin and NFTs.

So what are the options? The government would be better served to establish a cultural basic income in your city, state, country, etc., it would be cheaper than subsidizing these tech giants, raise the quality of life, and be healthier for the people and the planet. People could also reprioritize local handmade and lasting original cultural creations in their lives, rather than relying on the ephemeral nature of the dopamine-inducing quick consumption and discard pattern championed by capitalism. Finally, seek out and vote for governments that prioritize funding science and culture. For every dollar you feel was wasted on some nature experiment or sculptural piece you don’t like, know that way more was spent on creating real change and positively affecting lives. It is hard to see it on a grand scale, but like AI cannibalizing itself, it is hard to build a business or expand an economy with no new ideas, innovation, or joy, for that matter. Unlike the disproven trickle-down economy of capitalism, funding small-scale projects in culture and creative works by people does build into something greater than itself, having a positive lasting impact on the society we live in.

Pricing:

- White Stork of Andalucia – $950 CAD

- Red-tailed Hawk of High Park – $1850 CAD

- The Night Guardian – $650 CAD

- Widowmaker of the Savanna – $900 CAD

- The crucial nutrient cycle of whales – $85 CAD

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.artworkarchive.com/profile/nathan-cole

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/artist_ranger/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ColeTop10art

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/nathancole10/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/ColeTop10

- Other: https://www.twitch.tv/artistranger