Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Andra Watkins. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Andra, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

Every written piece should be labeled “Taking a Risk.” Even when a piece is not autobiographical, our stories reveal hidden bits of the creator.

I have a NYT bestselling memoir, but for much of my life I was afraid to write the truth of my upbringing. I was reared in a Christian nationalist, Moral Majority church and school. From my 20s to my early 40s, I rarely talked about it. I didn’t write about it because it was easier to try to forget, to pretend I was normal, to fit in. I didn’t want to relive that part of my life through writing.

When my state passed an almost total abortion ban, I decided I could no longer be silent. I poured my grief and rage into a Newsweek essay entitled, “I’m Childless Because of a Far-Right South Carolina Church.” I used my writing to educate my fellow Americans about how my upbringing shapes our political landscape today.

I was afraid of trolls; yes, I have been trolled. I feared vicious gaslighting from both family and members of my former congregation; they did not disappoint.

But sharing my story also helped young people navigating this new world of abortion bans. One red-state college student took my article to her mother and said, “This is me right now.” She started therapy. Another group of students were able to recognize unhealthy obsessive compulsive behaviors around birth control and seek help. Still others reached out to tell me they were proactively implementing longer-lasting, more permanent forms of birth control.

I risked telling this very personal story. My reward lies in the many readers it helped.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I always wanted to write, but I fell into writing by accident. The year I turned 40, the economy crashed. I went from a six figure consulting income to $10,000 in 2009. I didn’t know how to revive my consulting business. Instead, I started writing online.

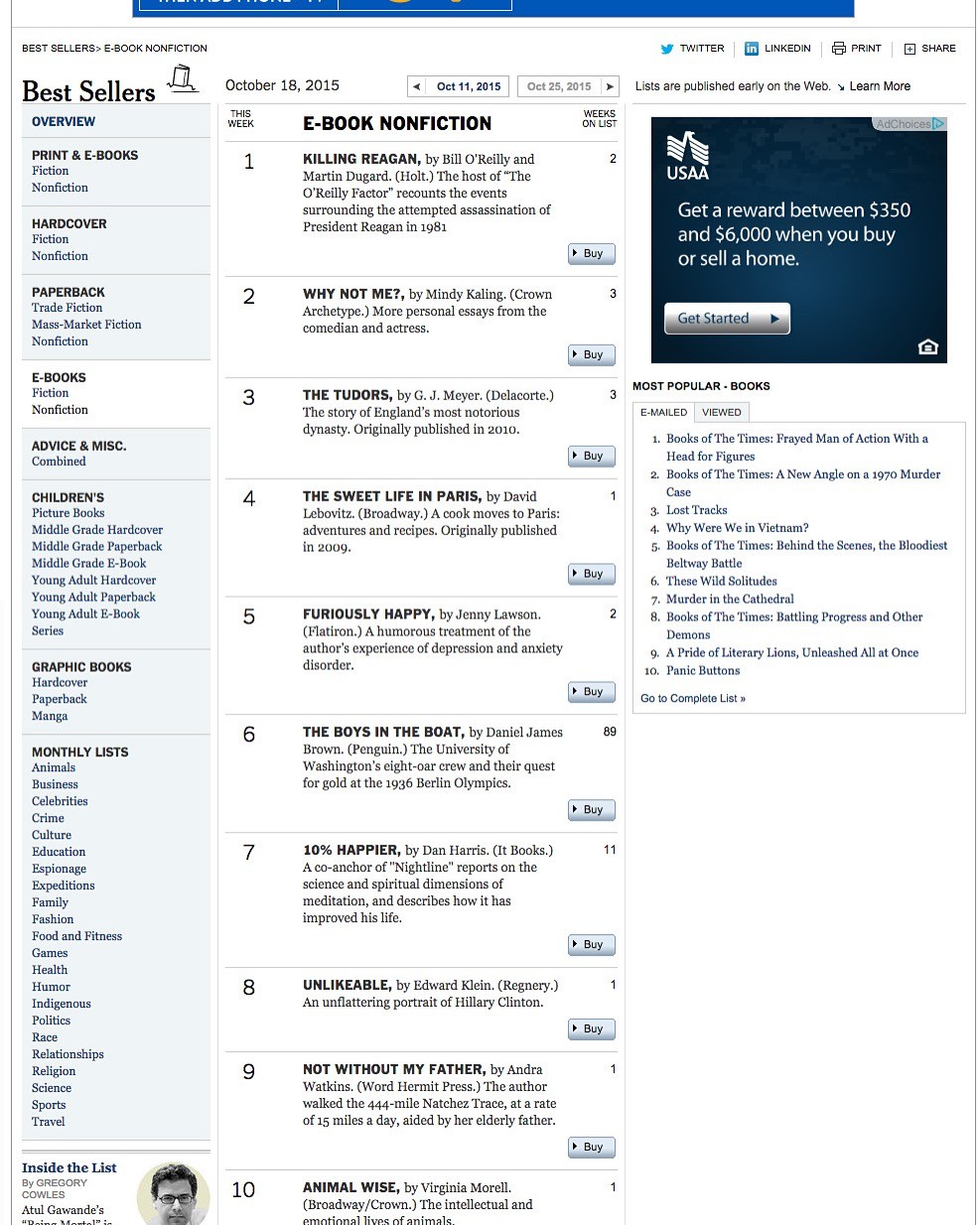

My online writing led to three paranormal historical novels and one New York Times bestselling memoir: Not Without My Father One Woman’s 444-Mile Walk of the Natchez Trace. But books were just the beginning.

I have spoken to groups on three continents. I have been a panelist at major writing conferences including the Southern Festival of Books and Pikes Peak Writers Conference. Major libraries have invited me to speak to their patrons. I have been published at major outlets including Newsweek and Salon.

And my accomplishments have been internationally acclaimed with writer-in-residence invitations in Iceland, Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland and Wales.

I wrote my novels because I wanted the escape they provided, and I hoped other readers would appreciate them for their differences. But I wrote my memoir to help people connect. I often say this in my speeches, but my memoir isn’t a story about me. That’s boring. My memoir is powerful because it convinces readers to turn my story into their stories, to make memories with people who matter before it’s too late.

On a more personal level, I’m married to the love of my life. I divide my time between Charleston, South Carolina and San Sebastián, Spain.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can provide some insight – you never know who might benefit from the enlightenment.

America hates creatives. I never really understood this until I became a creative myself. My family ridiculed me. Friends insulted me. Acquaintances belittled my accomplishments. While I have insulated myself from this noise, I spent close to a decade hurt and bewildered by the reactions of people who claimed to care about me.

Capitalism does not reward “creating for the sake of creating,” but that’s how all creating happens. I fill journals with words I will never publish to find a few ideas for essays and stories. Or I go live with other creatives for two months to try new writing techniques, something my family calls “flitting around Europe.” I take long walks when I can because they break up mental cement. I’m a font of ideas, though I’m much more selective about where I share those ideas today.

Creative work is work. It deserves proper compensation. When a reader buys a secondhand book, I make nothing. When someone downloads a pirated version of my work, it is theft. It is impossible for big publishers to police the internet for all the ways authors are robbed; imagine how helpless smaller authors like me feel.

The best thing a non-creative can do to support creatives is to pay actual money for their works. Encourage others to pay actual money for worthy works. Stop viewing creative pursuits as fanciful wastes of time and actually help creatives make a living.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

In 2016, I was officially diagnosed with toxoplasmosis gondii, a parasitic disease that impacts all major organs. It manifested in my retina, causing partial blindness. I joke that I’m lucky to be partially blind. An activation in the brain could cause seizures and dementia; in any other organ, an activation means death.

Unlike with cancer, parasites can only be detected when they destroy enough tissue. In my case, I saw a tiny black spot in one eye. That black spot grew to impact a quarter of my vision over the course of multiple rounds of chemotherapy.

Parasites don’t die; they merely lie in wait. It’s both true and trite to say we could die at any moment, but I see that reality every time I blink.

My doctors mistakenly gave me steroids with chemo, and they changed my whole personality. I woke up one morning at the age of 47 or 48, and I didn’t know who I was. Every tool I had ever relied upon to cope with being alive was broken or absent. It was like aliens came in overnight and replaced my essence with garbage. I talked gibberish and made no sense; I wrote piles of utter trash; for the first time, I pondered suicide. Me, a person who always prided herself on getting up no matter how many times life knocked her down.

I also learned how much my writing relied upon me. My brain was scrambled. I couldn’t write or coherently promote my work. My calendar looked like hieroglyphics. I could read something ten times and not understand what it meant. I hit the NYT bestseller list in 2015, and everything died in 2016 because I was too sick to promote it.

The years 2017 – 2019 were the darkest of my life. I sat in my house alone, grieving the death of a loved one, and I realized nobody was going to make sense of my new brain but me. I stopped hoping someone would finally understand what was happening to me, or would hold me and tell me it would be okay, and I decided to make the best of whatever life remained.

I embraced my value. And in the process, I found people who value me. My words flooded the page. I still struggle with my new reality, but I have better tools to cope. Because making memories in this moment is more important than bemoaning what I lost.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://andrawatkins.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/andrawatkins/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrawatkins

- Other: Substack: https://substack.com/@andrawatkins