We were lucky to catch up with Peter Young recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Peter, thanks for joining us today. One deeply underappreciated facet of entrepreneurship is the kind of crazy stuff we have to deal with as business owners. Sometimes it’s crazy positive sometimes it’s crazy negative, but crazy experiences unite entrepreneurs regardless of industry. Can you share a crazy story with our readers?

Two stories to highlight that the biggest entrepreneurial successes come from taking the biggest risks…

Before launching my software business, I was selling used books on Amazon. I was 35 with no resume, no skills, no degree, no family money, and no backup plan. I was on the fast track to suffering the fate of most of my peers (who I did not envy): working a non-profit desk job, driving for Door Dash, or some other sustenance-level work that stole most of their waking hours and left with only a paycheck in return.

II had been studying various “make money online” gurus for the past year, in desperate pursuit of the elusive seven-figure, one-person business, This was just before the internet was saturated with “make money” gurus. Making money online still had a subversive, underground feel.

On Halloween night my girlfriend and I cut through the lobby of the most expensive hotel in Boulder, Colorado, two blocks from my apartment. The lobby was roped off and a sign read “Closed for private event.” A large Halloween party was in full swing. Just as we were leaving to go around, one of those “make money on the internet” gurus I was following walks by. I didn’t know what this party was, but I knew we had to crash it.

We ducked around the velvet ropes, and once inside I spotted other familiar faces, including the CEO of Whole Foods.

We learned this party was the opening reception for an invite-only, $3,500 event called “Success Summit.” Among the speakers were various internet entrepreneurs, ostensibly teaching their secrets. Spending $3,500 was out of the question. Not attending this conference was also out of the question.

The next morning I was back at the hotel. When conference check-in person got distracted, swiped a pass and ran home. I quickly mocked it up on Indesign, printed it, then went to FedEx Office for a lanyard. Finally, I returned to the hotel, replaced the pass on the check-in table, and spent the next two days taking notes at the conference.

The last speaker pitched the “Software as a Service” (SaaS) model, describing it as “the ultimate freedom business.” The idea was to identify a pain for a specific business, hire a developer to build a software solution for that pain, then sell it to businesses a subscription basis. The monthly recurring revenue of a “SaaS” business allowed one person to scale to seven figures and beyond, with modest startup capital, and without learning to code.

I was sold. I went home, signed up for the speaker’s SaaS coourse, and went on to turn that into almost $10 million in sales.

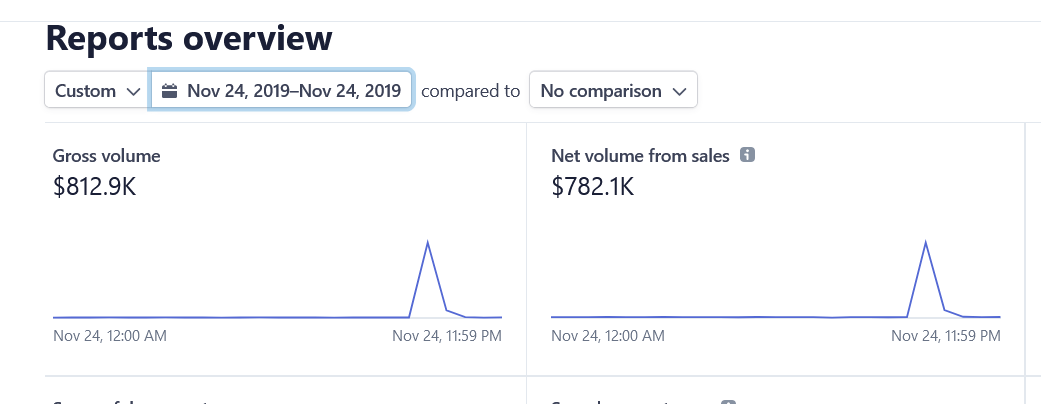

Story #2: Several years into the business, I was doing about $100,000 a month in revenue. I had an idea that I had no confidence would work, but I decided to try purely “for the plot.”

For several years I had saved every credible feature suggestion from every user in a spreadsheet. I gave the list to my developer and told him to build out an alternate, upgraded version of the software, with all these features added.

Then I announced this new upgraded version, available only one time, on a live webinar, and limited to 300 spots. I set a price of $3,500.

Up to this point, the most any customer had spent with me was $125 a month. I had no expectation more than 10 of my most die-hard power users would pay $3,500.

On the webinar, I sold almost 250 spots, making over $800,000 in one hour.

Peter, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

Everything that happened (business and beyond) is downstream of my decision at age 18 to never get a job, ever.

I called this my “militant unemployment experiment.”

In the early days, this took the form of developing small hacks that made money obsolete. I first found an abandoned house in a wealthy neighborhood on Mercer Island, Washington and lived there rent-free for two years (I would learn this home was owned by the Department of Transportation and unoccupied while caught up in legal limbo). With the biggest life-expense covered, I was able to live somewhat decadently by living off the excess of the wealthy suburbs east of Seattle—from grazing food at corporate parties I wasn’t invited to, to dumpster diving at Trader Joes.

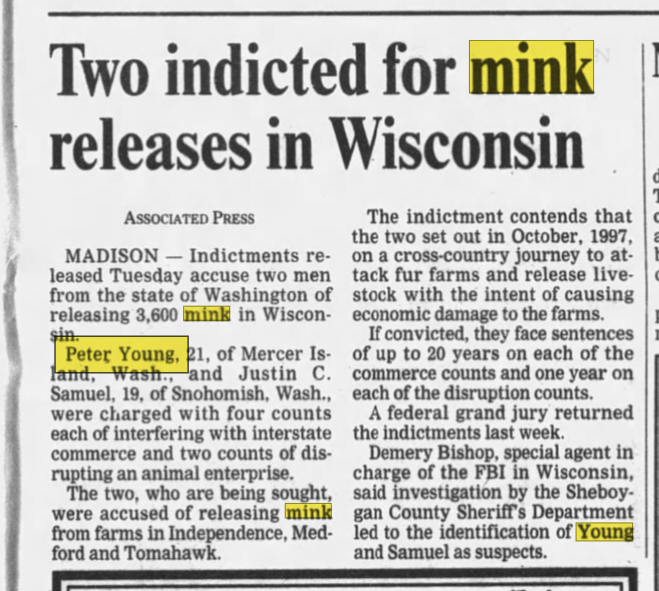

The stakes got higher at age 20 when I became the first person charged with “Animal Enterprise Terrorism” for my role in releasing thousands of mink from fur farms. Facing a maximum of 82 years in prison, I became a fugitive. I was on the run for nearly eight years.

This fugitive era would be a training ground for the entrepreneur era, which came later. Much of being a fugitive outlaw has business applications. From understanding influence and communication, to managing risk, to the bootstrapping mindset—all of this was forged during my time as a fugitive.

In prison, I preppd for a post-prison life where I would be forced to “play by the rules.” A hip hop artist a few cells down who went by “Luxury Jones” insisted that I read a book: Awaken The Giant Within by Anthony Robbins. The author was precisely the kind of “rich white guy” archetype that the world I came from rejected wholesale. But after persistence from Luxury Jones (that bordered on bullying), I read the book. The premise—that the quality of your life is the quality of your decisions and your communication (vs. nebulous external forces like “capitalism”)—was pure sacrilege in the punk rock subculture of my origins. But it explained why so many people I knew were so miserable and floundered beyond their 20s. It marked a small shift in belief that would later serve me well.

Post-prison, I read all the “starter pack” entrepreneur books like The Four Hour Work Week, flailing for a way to manage not having to sell myself to a boss (which I was good at), while also not going back to prison (not good at). Multiple obligatory failures and embarrassments followed, from a print on demand vegan t-shirt business to drop shipping soy milk makers.

It wasn’t until I began selling used books on Amazon in my early 30s that I attained a little business traction. After finally achieving a “middle class income,” I learned middle class was worse than poverty. When I was poor, I had nothing to lose, no overhead, and total time freedom. With my “successful business,” I had little free time, limited ability to travel, huge “responsibilities,” and meager profit left over for the sacrifice.

I decided that only the poor and wealthy are truly free. Having spent my entire life in the first category, I set out to achieve the second.

Around this time, I snuck into a $3,500 business conference and watched a speaker explain a business model called “Software as a Service” (SaaS). It was a challenging business, he explained, but if successful, many solo entrepreneurs were scaling to seven-figures in revenue (and beyond) without learning to code. And many were selling those businesses for millions and retiring young.

I was 35, with no prospects of not ending up a destitute 50 year old with roommates driving for Uber. After a breakup call in which my girlfriend essentially called me a loser, I went all-in on SaaS. I was technically inept, had no mentors, very little money saved from my Amazon bookselling business, and only one course to guide me.

Six months into brainstorming product ideas, I hired a developer. The tool I settled on was a solution to a small problem for a very small business niche. He delivered the final product in about six weeks.

In the first hour it was live, I had 100 subscribers sign up at $97 a month. It was a nearly $30,000 a month business on day one.

The business held flat at $30k to $40k/month for two years. From there, it climbed to $50k/month. Then $60k/month. Soon I had a $1million a year business.

It peaked at $120k/month recurring revenue. With a couple promotions and product launches a year, revenue was $2m+ for two years.

Six years after launch, I sold the business for multiple seven-figures and “retired.”

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

My big pivot happened at 33, when I looked around and realized no one I knew was aging well. This kicked off my transition from “punk rock activist” to “punk rock activist who doesn’t have to worry about money again.”

I came from a world that was part punk rock, part activist, part general leftist. None of it I disavow. But all of it created some uniquely miserable people. Everyone around me was in a death spiral by their early 30s. And I was the only one who saw it.

At this time I was living rent-free in an abandoned house with six roommates. The house had all utilities and no clear ownership, so punk rock kids had been living there in the open for years. I spent my days on various well-intentioned but ineffectual activist pursuits, did a lot of “hanging out,” and had zero vision of the future. .

At some point I looked around at the people around me and thought, “everyone’s life is in a nose dive, and we are all running out of time.”

You can better understand what I was up against in planning my escape by understanding the two main groups I saw around me.

One, the “followed their passions” people. They believed they were “living the dream,” while being largely blind to how poorly their lives had turned out. Working desk jobs at non-profits, touring in punk bands, or struggling as “freelance photographers.” All of it was “doing what you love,” but without a viable model to monetize, they ended up trapped and resenting the “passion” that was supposed to liberate them.

Two, the “systemic oppression” people. They had no illusions about their life working out. And they were absolved of any responsibility for it, seeing themselves as victims of “capitalism” or some perceived disadvantage outside their control. Failure masked as virtue.

I was 33, surrounded by all this failure, dressed up in the pretense of valor and righteousness. And I remember having a lightbulb moment: If I were to construct a set of beliefs to keep an entire segment of the population as permanent obedient wage slaves, it would look exactly like the beliefs of the world I came from—”the game is rigged,” no one can succeed under “capitalism,” there is no such thing as a self-made millionaire, etc etc. This mindset wasn’t just in conflict with freedom and autonomy—it was directly oppositional.

This was the indoctrination I was up against. A world of poor habits disguised as virtues. A subculture that engineers its own failure.

Approaching middle-age, I knew I had to make a half court shot at the buzzer to escape the fate of everyone I knew—or end up working until I died.

My pivot started with a massive belief-detoxification. Fundamentally, this was accepting that everything that happened to me was my fault. No one was going to save me. And to save myself would require huge risks. In the world I came from, all of these thoughts were subcultural thoughtcrimes.

Then I got very clear about what I wanted the next 10+ years to look like. I mapped it out down to the pixel. On a high level, this was escaping the resource acquisition treadmill entirely. Making enough quickly to never have to think about money again.

I started out reading like crazy. I stopped listening to people who weren’t where I wanted to be. Started building businesses and taking massive risks.

I was able to do everything in my ten year plan (and more) in well under ten years. Today I have time freedom, financial freedom, and don’t do anything I don’t want to.

Catching up with people from my past who never escaped is often interesting. The “punk to unhappy Trader Joes manager” pipeline has few survivors. I know many people now in their 40s who have sacrificed the second half of their life just to “keep it real.” They kept the approval of their peers, but sacrificed their entire life for it.

Some lessons I’d over to anyone from a similar background, looking to escape:

*Don’t take advice from anyone around you if you wouldn’t trade lives with them

*Related: offending people you would never trade lives with is a positive indicator (you’re on the right track—keep offending)

*What worked in the first half of your adult life, may victimize you in the second half (what got you to where you are, won’t get you to where you’re going)

*Your comfort zone is where dreams go do die (selling soap on Etsy is not an exit plan)

*To see what happens if you don’t pivot, look at your peers five to ten years older—that will be you (you will not be the exception)

*Embrace doing cringe things (none of it will matter when you win)

Can you open up about how you funded your business?

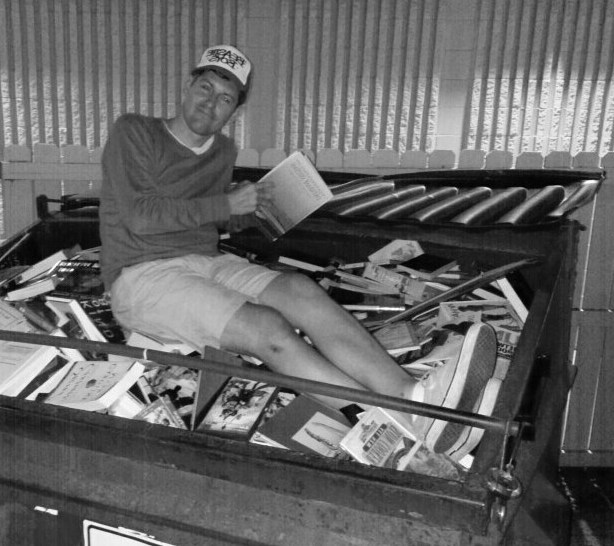

I bootstrapped my first software business in large part from reselling trash from dumpsters.

At the time, I was reselling used books on Amazon. It was the first business I started that generated consistent income (after several business failures). The bookselling model went like this: Install an app on your phone that tells you what books are worth. Go out anywhere there are used books (thrift stores, library sales, estate sales, etc). Scan the books. Pick the ones worth money (the percentage of profitable books was under 1%). List them for sale on Amazon. Repeat.

It was a crude but effective business that fairly quickly grew to six figures in sales. As someone who had been destitute my entire adult life, this was life changing money.

However, early on I understood the concept of leverage, and that real life changing money would only come from a business that was scalable. With books, every time I sold a book, I had to go out and replace it. Very difficult to scale. Within a year of selling books full time, I understood that books were only a placeholder.

Soon after I discovered the “software as a service” (SaaS) business model, and began rabidly saving my used book profits to launch a software business.

My single most lucrative source of used books was the dumpster of a library near my house. Every week they discarded thousands of books donated to them for their annual library book sale. The book sorter volunteers skimmed the most popular books from the donations (which were rarely worth money) and threw the most valuable books away. Every night I visited the dumpster and extracted every book of value. I didn’t track my revenue by source, but my profit from this library was easily into the four-figures a month.

That was the startup capital I used to launch my first software product, which I grew into a seven-figure business.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://peteryoung.me/

- Facebook: https://facebook.com/peter.young.forever

- Twitter: https://x.com/peterdyoung