Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Paul Abdella. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers and tell them a bit about what you do, your brand or organization and what makes it interesting/special/unique or anything else you would like them to know about you/your story/your brand and what you are working on/etc.

I’m Paul Abdella — a martial artist, teacher, and artist. Those three threads have been woven through my life since childhood. I began martial arts as a kid, drawn first to the athletic and competitive side, and later to self-defense and practical reality-based systems. Eventually, the search for depth led me to the Chinese internal arts, and to T’ai-Chi Ch’uan (Tai Chi) — the art that became my lifelong path.

Today I serve as the Chief Instructor and Executive Director of Twin Cities T’ai Chi in Saint Paul, Minnesota. I teach the Yang Family style of Tai Chi, passed down to me through my teacher T.T. Liang (Liang Tung-tsai), who was born in 1900 at the end of the Qing dynasty and lived to102. Through his direct connection to the early masters, I’m able to teach a complete traditional Yang-style system, including the Solo Form, two-person Pushing Hands, classical weapons, Qigong, and meditation.

After more than 40 years of study and practice, I created the Tai Chi Symmetries Form, a two-person version of the Solo Form that explores all its martial applications in a relaxed, flowing way. I’m currently editing a new online course on the Tai Chi Solo Form, which will soon be available to the public — the first in a series of offerings designed to make authentic, lineage-based Tai Chi accessible to a wider audience.

What do you think is misunderstood about your business?

I think many people see Tai Chi as simply a slow, graceful exercise. Tai Chi has far more depth and breadth than people realize–it’s a complete system with four interconnected aspects.

The first is health. Tai Chi teaches us how to move efficiently and in a way that keeps the body structurally aligned and grounded. That connection to the ground builds better balance, leg and core strength, and flexibility. The slow, flowing movements also encourage deeper breathing, which activates and regulates the parasympathetic—or “rest and relax”—part of the nervous system.

It’s one of the reasons people feel calmer and more centered after a class.

The second aspect is mind-intent. To practice Tai Chi is to train the mind as much as the body. It requires focused attention — integrating concentration, memory, and the awareness both of our internal sensations and our position of the body in space.

The third aspect arises when a relaxed body, slow deep breathing, and a quiet mind come together. This integration leads to a state of moving meditation, where brainwave activity slows and the practitioner experiences reduced stress, clarity, and a calm, peaceful state of mind.

The fourth aspect comes from Tai Chi’s roots as a martial art. It’s based on the principle of yin and yang — two complementary forces that can’t exist without each other. In practice, the yin side involves yielding, neutralizing, and redirecting an opponent’s force, while the yang side releases energy, called jin, to counterattack and overcome brute force.

Tai Chi practitioners have understood these principles for centuries, and science is now confirming them. Each year, more than a hundred clinical studies validate Tai Chi’s wide-ranging benefits — from improved balance, strength, and flexibility to enhanced cognition, mood, and immune response, and even reductions in chronic pain and disease.

The beauty of Tai Chi is that it keeps deepening. With a good teacher and steady practice, its benefits continue to unfold — quietly, profoundly, and for a lifetime.

What was your earliest memory of feeling powerful?

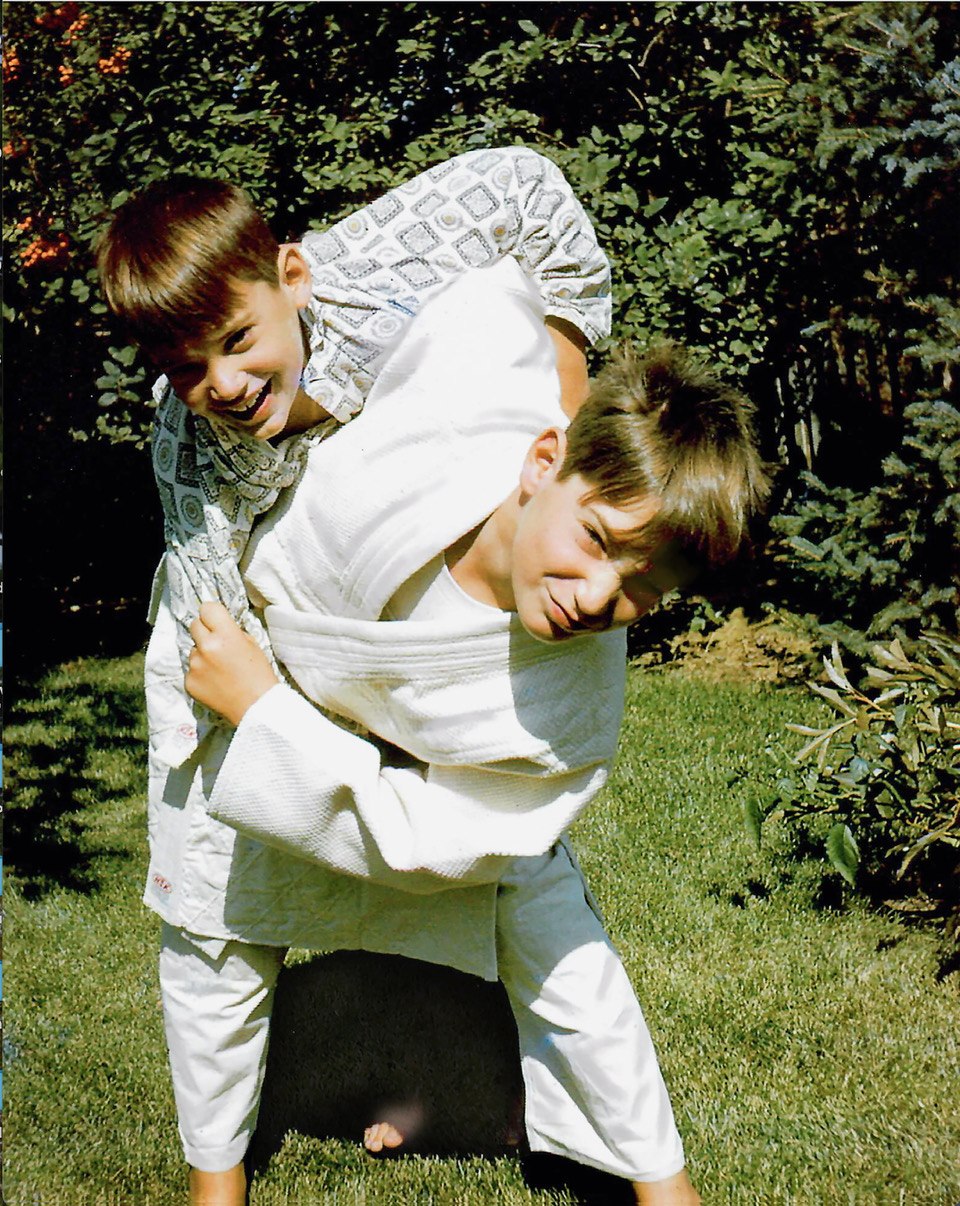

When I was a young boy, I asked my father if I could take boxing lessons. He didn’t answer at first, but later he said I could sign up for a judo class that was starting in a few weeks. Although I really wanted to learn to box, the idea of knowing how to throw people around like I saw on TV and in the movies made me quickly forget about boxing.

The judo school offered a six-week introductory course — a trial period to see if you liked the practice and could handle the training. If you made it through, you could join the main club. I convinced my best friend to sign up with me, and my dad drove us to our first class and dropped us off at the door.

The class began with a lot of calisthenics to warm up. They were difficult, and many of the exercises were things I had never done before—pulling yourself face down across the mat using only your forearms, duck-walking up and down stairs with your hands clasped behind your head, and a kind of push-up that moved forward and backward as well as up and down, which they called judo push-ups. There was also abdominal work—a lot of it. It was a three-hour class, and we spent about the first hour doing calisthenics. I was already exhausted, but curiosity about what came next kept me going.

Then we began learning roll falls—tumbling forward, backward, and sideways—to prepare us to fall safely when thrown. The instructor called this Ukemi, a Japanese word that meant “to receive with the body.” Physically, it taught me how to fall, roll, and be thrown without injury. Psychologically, it cultivated acceptance, adaptability, and the idea of meeting force with yielding rather than resistance. My ten-year-old self thought it was a lot more fun than calisthenics. Over time, Ukemi became a kind of philosophy for me—a way of cultivating receptivity, humility, and a sense of flow while navigating life’s challenges.

By the end of those six weeks, I was all in. My friend had dropped out, but I joined the judo club. A few months later, once I’d learned the basics — how to fall, how to throw, how to grapple — we were told to pair off and compete. I was matched with someone a bit bigger than me. When the match started, I relaxed and moved the way we’d been taught, trying to find my moment. I came close to throwing him a couple of times, but the real turning point came when he tried to throw me.

I felt his intention through the contact of our hands and arms — that tiny, almost imperceptible shift that comes just before someone commits to movement. Without thinking, I adjusted, and his throw never happened. It was as if I’d read his thought through touch.

That moment stayed with me. Through those early months of judo, I learned that power wasn’t about force or domination — it was about awareness, focus, and adaptability. I discovered that if I kept my attention steady and my body relaxed, I could meet challenges — both on and off the mat — with the same receptive strength. Years later, I would realize that this early lesson in Ukemi and sensitivity to intention was the foundation for everything I came to study and teach in Tai Chi.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

There have been four times when our Tai Chi school nearly closed. The first was after the financial crash of 2008. The second came when light rail construction began along the busy corridor where our school is located. For months, the road was torn up and access was blocked — businesses all around us shut down, but we managed to survive.

The third time was when our former chief instructor left abruptly, taking much of the board and membership with him. It splintered the school and nearly ended it. It took months of steady effort to rebuild and restore membership and a sense of community.

And then came the pandemic of 2020. When our governor ordered businesses like ours to close, I turned to whatever tools I had. I made instructional videos, posted them online, held classes in a nearby park, and eventually began teaching on Zoom — something I’d never done before. Slowly, we rebuilt again.

Any one of these might have been reason enough to give up. But by then, I had decades of Tai Chi practice behind me. The physical training helped me stay grounded and relaxed, while the philosophy gave me perspective.

Tai Chi is rooted in the Dao — the natural, underlying order of the universe — where change is constant and inevitable. The nature of yin and yang is cyclical: when one force reaches its peak, it naturally transforms into its opposite. The height of success holds the seeds of decline, just as every low point carries the potential for renewal. No state is permanent.

In stillness, clarity arises — a vision of what to do next emerges, and the right people are drawn to help you do it. That may sound counterintuitive, and it’s not always easy, but it is the way — Tai Chi’s way — of effortless action.

In the end, the true reward of a dedicated Tai Chi practice is the ability to move well and enjoy good health throughout life. One of the classical writings asks, “What is the purpose of this discipline?” and answers, “To lengthen one’s life, extend one’s years, and give one an ageless springtime.”

I have seven grandchildren. The three youngest of my four granddaughters all study dance, and when we’re together, they love to show me their latest moves. Before long, I join in — and they’re amazed that at 69, Papa Paul can still pull off a perfect cartwheel, and on a good day, drop into a front split.

My teacher, T.T. Liang, used to say, “Life begins at 70.” He would often add, “Still, you can’t stop the sun from traveling east to west.” True enough. But sometimes the most beautiful light happens late in the day.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.tctaichi.org/

- Email: [email protected]

Image Credits

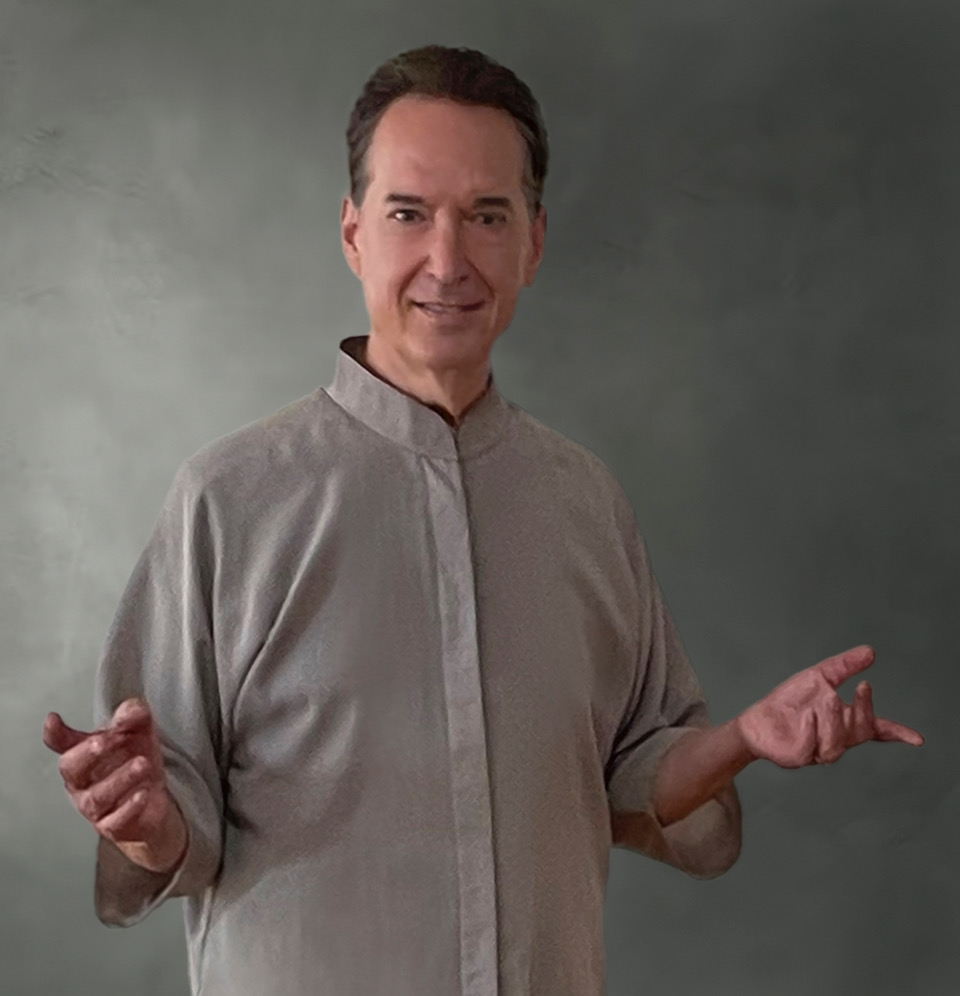

Personal Photo

Photo #1.

Standing Portrait

Photographer: Tom Reich

Additional Photos

Photo #1 A Tai Chi Class

Photographer: Stephan Kistler

Photo #2 Paul performs the Tai Chi movement–Squatting Single Whip

Photographer: Stephan Kistler

Photo #3 Paul and Instructors perform the Tai Chi Cane Form

Photographer: Stephan Kistler

Photo #4 Paul and Instructor Kim Husband perform the Tai Chi Symmetries Form

Photographer: Stephan Kistler

Photo #5 Travels in China 2016

Photographer: Sylvia Sim

Photo #6 10-year old Paul in his Judo Gi with brother Joel in his pajama Gi

Photographer: Paul’s father Edward

Photo #7 Paul and Grandmaster T.T. Liang practice Tai Chi Sword with Tassel 1984

Photo #8 Paul and his dancing granddaughters

Photographer: Mary Wynne

Suggest a Story: CanvasRebel is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know here.