We were lucky to catch up with Lin Hu recently and have shared our conversation below.

Lin , looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. We’d love to hear the story of how you went from this being just an idea to making it into something real.

When I consider how a project moves from idea to execution in architecture, I see a multi-layered process that is very different from, say, product design or art. Architecture engages not only with aesthetics and forms but also with human-centred experience, materiality, site context, zoning and code compliance, community resilience, and many other layers.

When a client assigns us a project, the site – its location, physical conditions, and context – comes along with it. From the outset, this reveals constraints and opportunities. At this stage we meet with the client and establish clear project goals. For example: a commercial-oriented, pedestrian-friendly neighbourhood development. We gather data from the site itself and from engineers: utilities, existing infrastructure, services that may be missing, surrounding urban fabric, zoning and code constraints, etc. This process helps us understand what forms are possible, what kinds of interventions make sense, and the background “big picture” of the city or community the project will join.

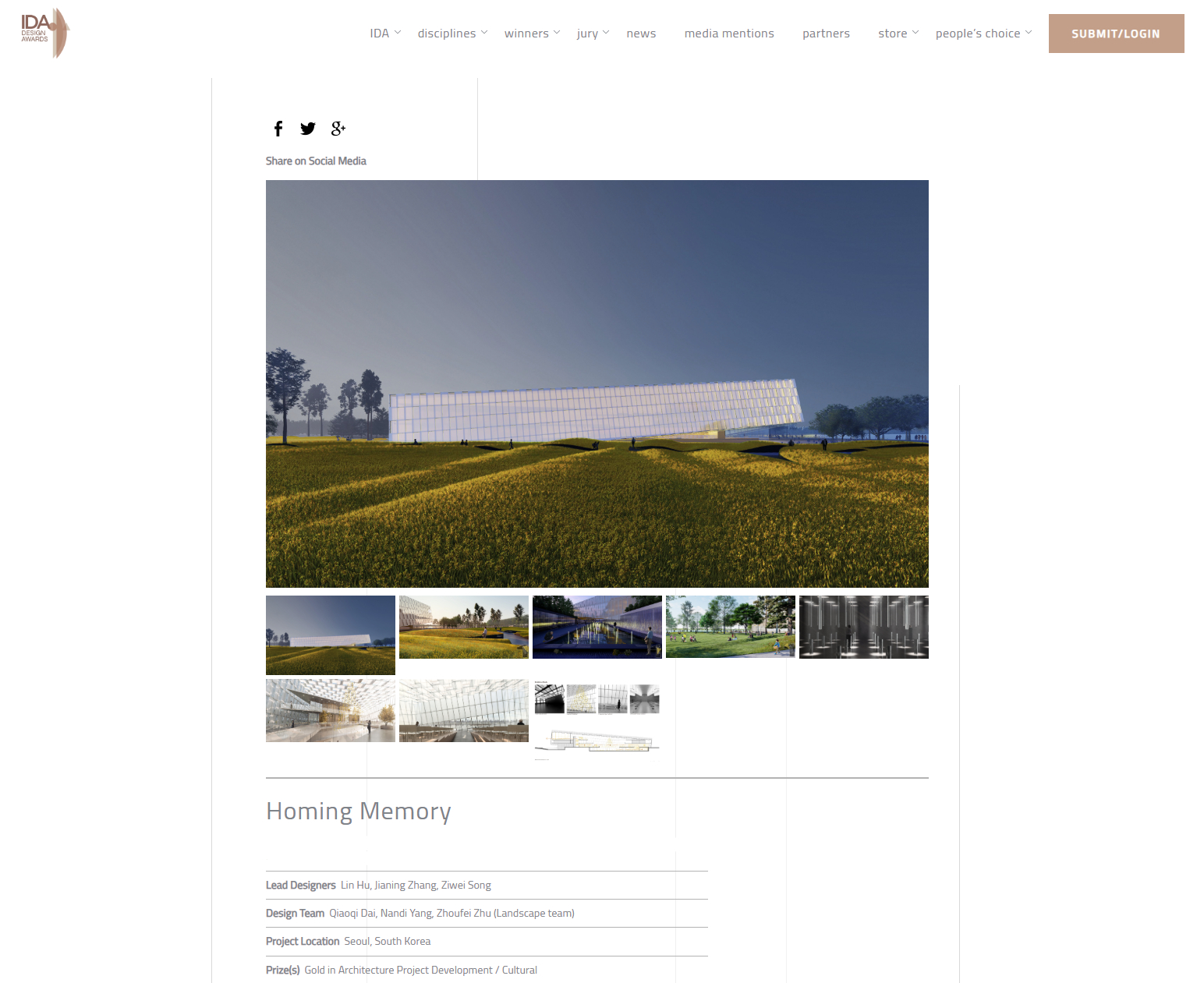

With that groundwork in place, we propose a design concept that is rooted in the site’s realities and the client’s goals. Because the architectural process is so bound to context, many of the best design ideas emerge from the site itself. For example: in my memorial-museum project in Seoul, South Korea (commemorating victims of the 416 ferry tragedy), the massing concept mimicked the sinking ferry, allowing visitors to feel a connection to the event. The building was oriented toward the lake to take advantage of the waterfront view and integrate meaningfully with the site.

Once the concept and program are established, the next crucial step is to validate feasibility, especially financially. Unlike many product designers who may first envision a bold idea then design toward revenue afterward, in architecture the client usually brings a fixed construction budget from the start. If the cost to realise the idea is too high, we must revisit the program, adjust building size or quality of materials, or refine the concept in order to stay within budget. This ensures the project remains viable and responsible. Architectural projects, especially large scale ones, are often a 10-year horizon from initial study through construction. It’s essential to pull together the right team across experience levels, for instance, senior architects, mid-level designers, younger staff, to guard against budget overrun and ensure continuity. We align the team around the shared goal to avoid duplicated work or misaligned efforts, and we monitor time spent versus schedule to maintain progress and efficiency.

Finally, once the full package (drawings, specifications, permit approvals) is ready, we move into construction administration. This is where we ensure the built work aligns with the design intent: materials, finishes, detailing and quality control all matter. This stage realises the original concept in the real, physical world and involves constant coordination with contractors, engineers, and the client.

In essence, moving from idea to execution in architecture means engaging deeply with context, goals, budget, team and construction, not just chasing a bold idea, but realizing it within real-world conditions.

Lin , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I am an architectural designer in bay area. My career path was inspired early on by my mother, who is an electrical engineer, but in her projects she was designing beautifully creative transformer systems, which introduced me to the idea that engineering and design could be expressive. As a child I always had a strong interest in art and built works; my school drawings often envisioned future buildings and repeatedly earned awards. During my undergraduate studies I grew particularly drawn to sustainable design and resilient community strategies through architectural concepts that bridge the gap between individuals and society. After completing my Master’s in Architecture at University of California, Berkeley, I decided to devote myself fully to the architectural industry, combining my longstanding passion with my commitment to meaningful, socially-aware built environments.

Accredited as a LEED AP, I have led projects that champion resilience, efficiency, and inspiration in the built environment. My work spans diverse sectors – including multifamily housing, civic and workplace design, educational facilities, and transit-oriented developments.

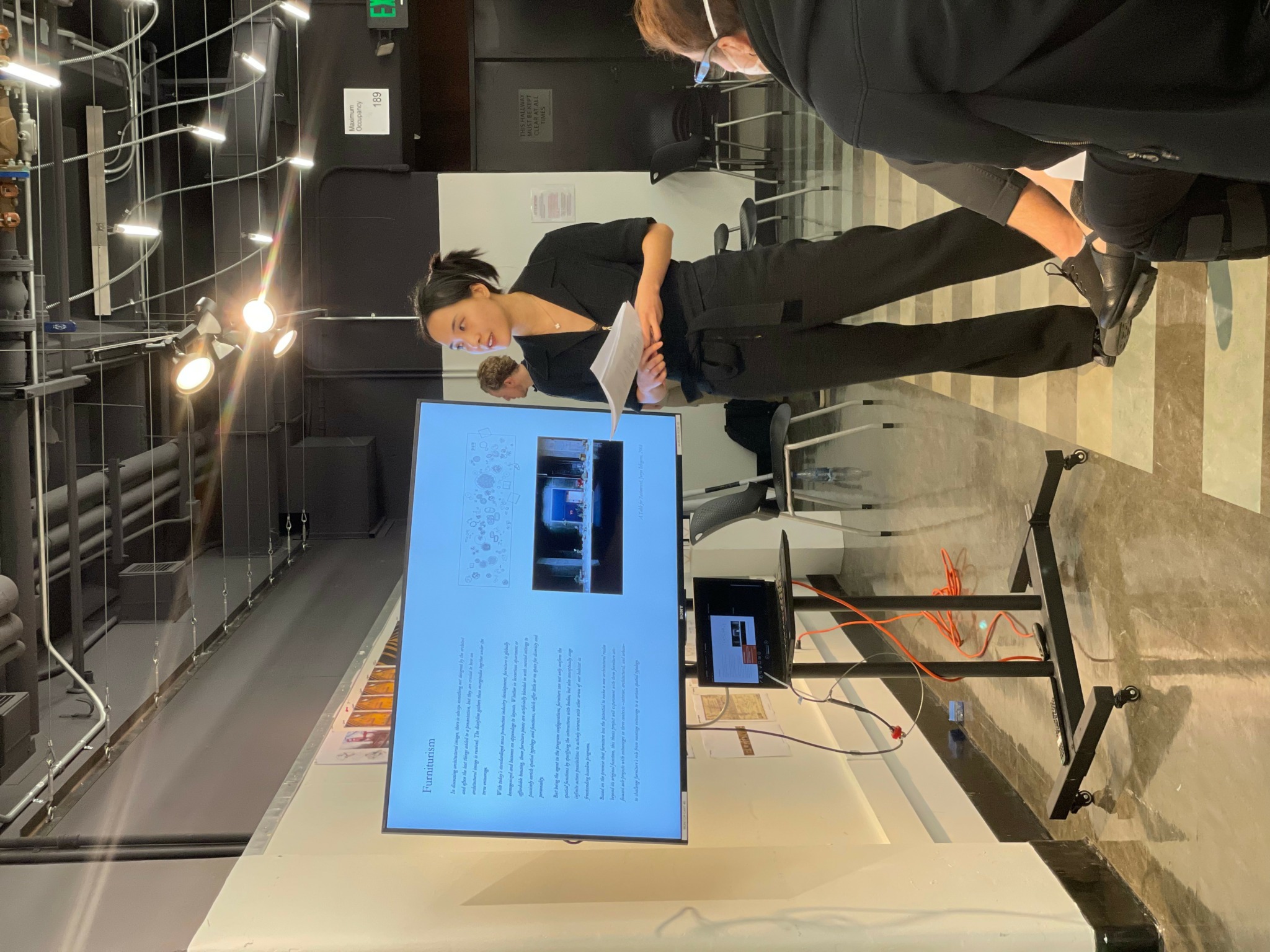

My design leadership has been recognized internationally, earning distinctions such as the IDA Gold in Architecture, DNA Paris “Emerging Architect of the Year”, and Red Dot 2023 Winner. My projects have been featured in leading design platforms including UnbuiltArch and Gooood, and I also contribute to architectural discourse as a design critic at the California College of the Arts.

At the heart of my work lies a deep passion for exploring how architecture can evolve with society. I am driven by the challenge of translating sophisticated design philosophy into practical, human-centered spaces-creating environments that not only respond to today’s needs but also anticipate the transformations of tomorrow. My fascination with architectural typology and cultural continuity guides me to rethink spatial systems, embrace emerging technologies, and connect history with innovation.

Looking back, are there any resources you wish you knew about earlier in your creative journey?

I used to think creative design in architecture was mainly about designing the building itself, its form, material, and structure. But I often overlooked the importance of entourage and context. Reading Michael Young’s Aesthetics, Digital Images and Architecture really opened my eyes to this idea.

This book challenges how I think about visual expression in architecture, showing that images, renderings, and representations are not just tools to present a design – they actively shape how people perceive and experience space. It explores the idea that the images we create, whether through drawings, renderings, or digital media, are not merely representations of design – they are powerful tools that shape perception, influence interpretation, and even guide how people engage with space.

What struck me most is how Young emphasizes the subtle yet profound role of context and entourage – the elements surrounding a building or space that might seem secondary, but actually contribute significantly to the overall experience. This perspective encouraged me to see beyond the obvious components of a design and to consider how everything in the environment – landscape, neighboring structures, light, and even temporary installations – can interact with and amplify architectural ideas. It reminded me that design is rarely isolated; it exists within a network of visual, cultural, and social influences that can be leveraged thoughtfully to enrich the experience of a place.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

For me, the most rewarding part of being an architectural designer is seeing my work contribute to the community, helping to create neighborhoods that are more sustainable, resilient and vibrant. When a project I’ve worked on helps people live healthier, walk more, gather more, and feel more at home – that’s deeply fulfilling. It’s especially satisfying when we overcome constraints (budget, site, regulatory) and still deliver something that positively affects how people live, how a place is used, and how it evolves over time.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: takii.hu