We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Tommy Wan a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Tommy thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Let’s jump into the story of starting your own firm – what should we know?

Among the karaoke bars, orchid shops, halal butchers, sari stores, dim sum restaurants, taquerías, African groceries, Zen meditation centers, and Persian rug dealers that line Bellaire Boulevard in west Houston is my home community: Alief. I still remember the exact moment I realized Alief needed its own voice for youth leadership. It was summer 2022, and I was sitting in a Houston City Council meeting during my internship at District F, watching as issue after issue affecting my home community got pushed to the end of the agenda, discussed in hurried five-minute segments, or simply deferred to future meetings. Alief was often referred to as the “forgotten district.” District F, where more than 93 languages echo through apartment complexes and community gardens, is home to Vietnamese refugees, Nigerian immigrants, Hispanic families who’d been here for generations, and we had little political power. Our voter turnout was low. Our young people had limited opportunities to engage in civic life. That summer, we launched AliefVotes, working with the youth in the community and with the steadfast support of Council Member Tiffany D. Thomas.

My first office was my childhood bedroom in Alief. My first board meetings happened over FaceTime with high school friends scattered across different colleges. My first major event, a voter registration drive, drew exactly seven students to the parking lot of a grocery store in Alief. I had this romantic vision that if you just created the organization, people would show up. What I learned very quickly is that authentic organizing in immigrant communities requires trust, and trust takes time to build. Relationship building became everything. The breakthrough came when I started showing up consistently at places where Alief young people already gathered. The Alief Community Garden, where multi-cultural families grew lemongrass and Nigerian grandmothers tended collard greens. The yellow shipping container where the WOW Project distributed food every Sunday. High school parking lots after football games. As my father drives our family to dinner on Bellaire Boulevard through Little Saigon and Chinatown, my nose pressed against the barren, reflective windows of our 2010 Mazda Van, I peek outside and take a moment to ponder proudly.

Indeed, Alief is more than my home in Houston. It’s a powerful mosaic of sari stores, taquerías, African groceries, iglesias, dim sum spots, and Islamic masjids lining Bellaire Boulevard. It’s a community defined by cultural prowess, working-class grit, and a sense of solidarity. However, Alief is burdened with the weight of deep-rooted challenges, including environmental injustices, low-propensity voting, infrastructure needs, civic neglect, and the title of the forgotten district in local representation. Civic engagement is the bedrock of our communities. As a majority-minority neighborhood in Southwest Houston, we rely on an informed citizenry, civic participation, critical thinking, and opportunities to empower the next generation of youth leaders. Yet, in the heart of Alief, youth engagement has historically been an afterthought.

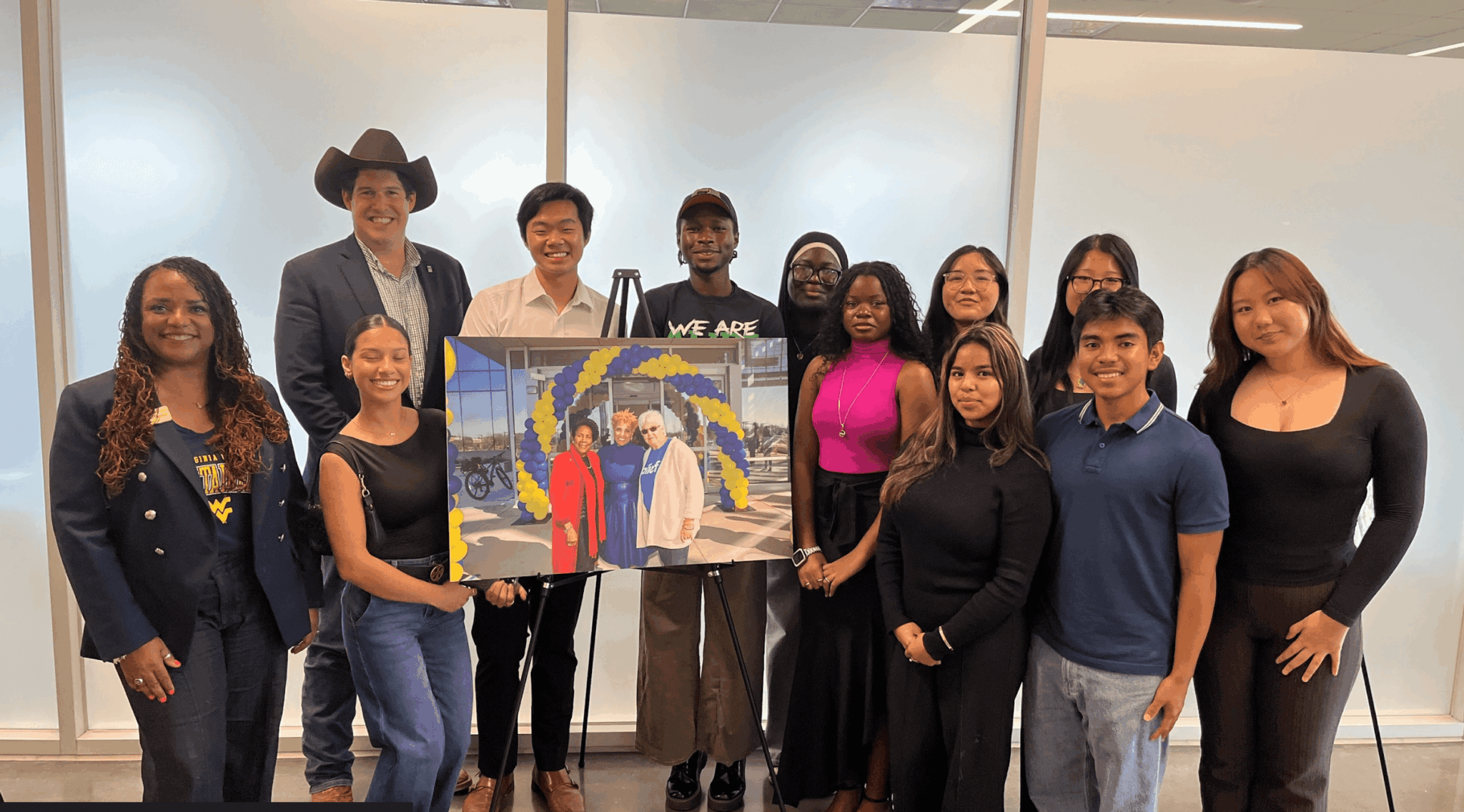

I was born and raised in Alief. Faced with this stark lack of opportunities, we founded AliefVotes in 2022, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to equipping Alief ISD students with the tools of civic engagement. Youth leadership empowers me daily. The late Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm proclaimed that if they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair. The proclivity for community leadership that I see through youth involvement in Alief ISD, in the heart of Southwest Houston, is empowering. From hour-long Zoom check-ins about project ideas to seeing students testify about capital projects in front of the Harris County Commissioners’ Court, my heart is warmed by seeing intergenerational leadership in our collective communities.

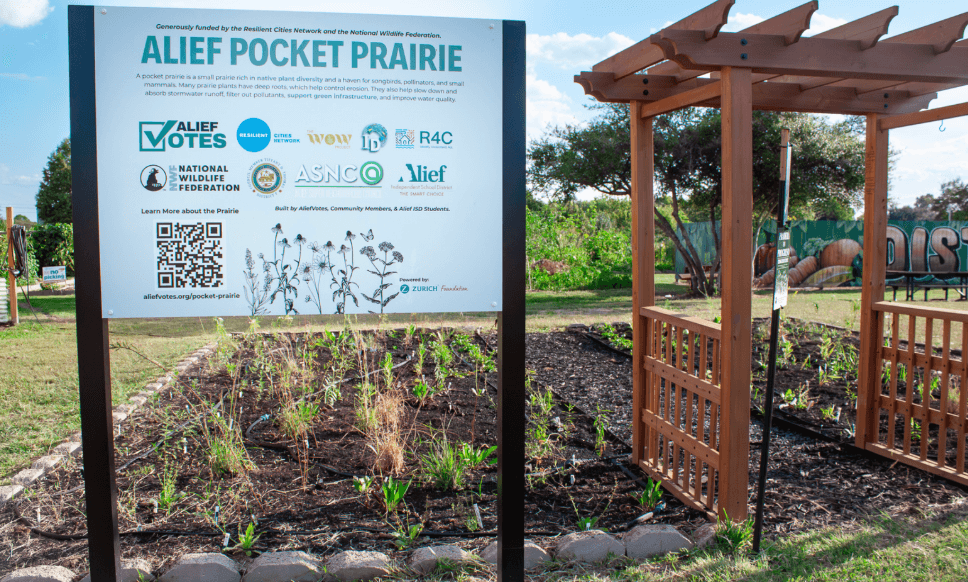

Another pivotal point came when students approached us with concerns about extreme heat and environmental injustices in our neighborhoods, where the lack of green space and concrete created dangerous temperature spikes. Rather than dismiss the idea as too ambitious for a new organization, we spent months teaching grant writing, environmental science, and project management. We held four community meetings in multiple languages, letting residents choose between different green infrastructure options. When pocket prairies won overwhelmingly, we coordinated with master naturalists, irrigation specialists, landscape architects, and dozens of volunteers to create educational installations that now serve as gathering spaces for families. What was prideful was learning to be a real partner to community organizations that had been doing this work for decades. Groups like the Alief Super Neighborhood Council, the Resilient Cities Network, the National Wildlife Federation, and the WOW Project had to trust that young people could deliver on promises.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

Hello! My name is Tommy. I am currently a senior at the University of Texas at Austin studying civil engineering, government, and Plan II Honors with a certificate in public policy. I focus on the intersection of infrastructure systems, urban policy, and community resilience, with research and applied experience in engineering analysis, local government, youth civic engagement, and public engagement. My academic and professional work integrates civil and environmental engineering principles with urban governance and policy frameworks to advance equitable and sustainable infrastructure outcomes. Most importantly, the deep intentional mentorship of youth in Alief ISD is most gratifying.

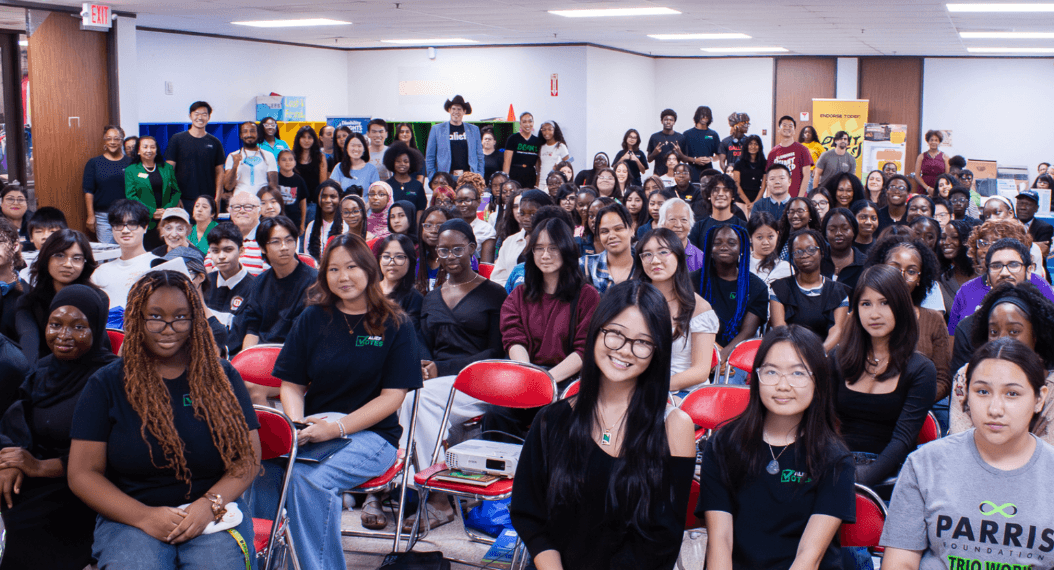

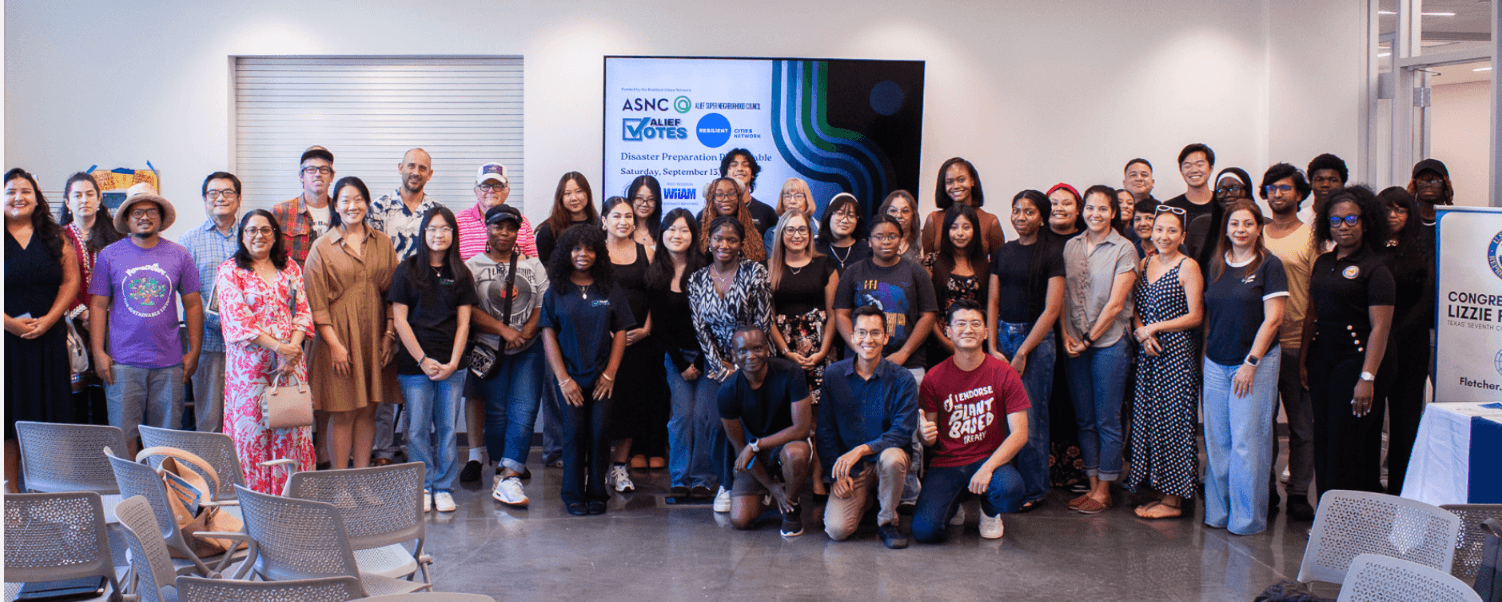

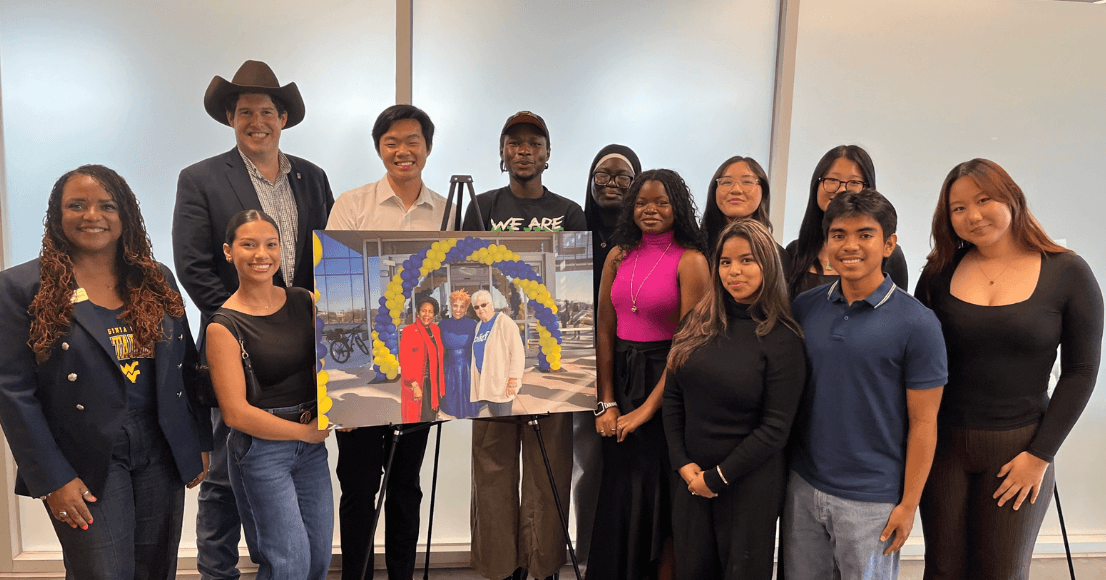

As Founder and Program Director of AliefVotes, I oversee youth civic engagement, environmental resilience, and policy education programs across Southwest Houston. Under my leadership, AliefVotes has raised over $400,000 in grants, secured $390,000 for tree-planting and green infrastructure projects, and engaged 8,549 students and stakeholders from Alief ISD. I manage strategic partnerships with the Resilient Cities Network, the National Wildlife Federation, and the Alief Super Neighborhood Council, coordinating projects on disaster preparedness, urban heat mitigation, and environmental education that collectively mobilize 315,330 volunteer hours.

At UT’s Cockrell School of Engineering, I work as a Research Assistant and Academy of Distinguished Alumni Research Scholar under Dr. Kasey Faust, Dr. Kerry Kinney, and Dr. Michaela LaPatin, where I apply mixed-methods analysis and spatial modeling to study urban heat, air quality risks, and sociotechnical infrastructure interdependencies. I am the first author of a peer-reviewed paper on the vulnerabilities of permafrost-dependent water infrastructure in Western Alaska, published at the 2025 World Environmental and Water Resources Congress. Currently, I’m developing my senior thesis on urban heat and air-quality risk modeling, integrating Dedoose-based qualitative coding with GIS spatial analytics to examine sociotechnical interdependencies across infrastructure, land use, and policy networks. The work examines fence-line resilience, air quality perception, and policies in Beaumont and Port Arthur, Texas, employing mixed-methods approaches that include community focus groups, technical air quality monitoring using Corsi-Rosenthal boxes and silicone wristbands, and GIS spatial analysis.

I currently serve as an Energy Policy Intern at PowerHouse Texas, a nonprofit advancing bipartisan energy innovation and legislative research. My work supports the Energy Policy Advisory Council, where I develop policy briefs on nuclear energy, grid modernization, and water-energy interdependencies. I also assist with statewide Energy Innovation Tour logistics, focusing on solar and energy independence, and contribute to program development and C3 fundraising.

Beyond government and engineering, I am a Future Leaders in Law Fellow at Harvard Law School, a Community-Based Mentor with the Carnegie Young Leaders Program, Federal Policy Associate with Students Engaged in Advancing Texas, a Civic Influencer Fellow, a Bill Archer fellow, a Truman Scholar Finalist, an Environmental Justice Fellow with Mi Familia Vota, and an E Pluribus Unum Youth Fellow focused on environmental equity. On campus, I have served as Forum Editor for The Daily Texan, Treasurer and Competing Attorney for Texas Mock Trial, and Director of Access, Engagement, and Advisory for the Texas Rocket Engineering Lab, managing initiatives to expand equity and participation in aerospace research.

My technical and policy interests include infrastructure resilience, capital improvement planning, community development, water and wastewater rehabilitation, transportation and aviation systems, as well as Texas energy and climate policy. I hold a Private Pilot License from the Federal Aviation Administration and have performed with the National Youth Wind Ensemble in Washington D.C., Houston Symphonic Band, TMEA All-State Band, as Nord Anglia Musician of the Year, and as a Classical and Jazz Instructor at Through The Staff. In my free time, I enjoy running, playing classical and jazz saxophone, composing, flying single-engine planes, competing in mock trials, conducting engineering research, reading nonfiction, and playing pickleball and tennis.

I hope to graduate with a Master’s in Public Policy and a Juris Doctorate after completing my undergraduate studies, continuing this work of ensuring that infrastructure systems serve communities equitably and sustainably.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

In the heart of Alief, Houston’s “little United Nations,” where over 93 languages echo through its streets and gardens, a remarkable transformation began not with politicians or planners, but with students and community leaders who refused to accept that their community’s future was written anywhere except in their own hands. This is the story of how youth leadership, environmental justice, and true collaboration converged in one of America’s most beautifully diverse communities to create not just pocket prairies but a blueprint for climate resilience that honors every voice.

Alief has long been called the “forgotten district,” City Council District F, systematically overlooked despite being home to tens of thousands of immigrants, refugees, and working families. When students learned that Alief, along with Gulfton and Sharpstown, ranked among Houston’s most vulnerable neighborhoods to climate change and extreme heat, we took action.

The story truly begins in early 2024 at the Alief Community Garden, seven acres at the corner of Beechnut and Dairy View that ABC13 news called a “little United Nations.” Here, Vietnamese gardeners tend rows of Thai basil, purple perilla, and lemongrass. Burmese families cultivate bottle gourds in wooden trellises for traditional soups. Nigerian growers nurture varieties of peppers that connect them to ancestral lands. Pakistani gardeners coax onions and winter melons for curry. Congolese women, barefoot in the soil, tend cabbage and sweet potatoes.

When AliefVotes students sat in community meetings listening to these neighbors share stories of flooding, unbearable summer heat, and lack of green space, they recognized something profound: their community already knew how to be resilient. They just needed support to build the infrastructure that matched their vision. The students, many of them children of immigrants themselves, fluent in the languages and cultural nuances of their neighbors, became the bridge between community wisdom and institutional resources.

Through four meticulously planned, student-led community meetings at the Alief Neighborhood Center in late 2024 and early 2025, young people, in collaboration with the Resilient Cities Network and the National Wildlife Federation, facilitated conversations that honored Alief’s magnificent diversity. Student leaders Ninet Flores Miranda and Mia Nguyen stood before their neighbors on February 6, 2025, presenting climate resilience options in accessible language, with interpretation services ensuring every voice could be heard. They explained tree planting, bioswales, rain gardens, and pocket prairies not as technical jargon, but as solutions rooted in community needs. In this process, we would like to thank Jordana Vasquez and Kavyaa Rizal from the Resilient Cities Network, Kate Unger, and Marya Fowler of the National Wildlife Federation, and Dr. Alan Steinberg and the late Ms. Barbara Quattro from the Alief Super Neighborhood Council.

On March 18, 2025, at the final community meeting, residents voted. It wasn’t a simple show of hands. It was democracy in its most valid form. Elders who remembered the 600,000-acre Katy Prairie before urbanization shrank it to 200,000 acres cast votes alongside teenagers born in Houston but dreaming of a greener future. When pocket prairies won overwhelmingly, students didn’t just implement a decision. We took action, and it worked.

What followed was a masterclass in youth-led organizing. Students reached out to the National Wildlife Federation, where Kate Unger (Resilience in Schools Coordinator) and Marya Fowler (Director of Education and Outreach) saw something special in these young leaders. Rather than treating them as participants, Kate and Marya became true partners, spending countless hours teaching students everything from prairie ecology to project management.

Through fifteen intensive planning meetings from January through September 2025, students learned that successful environmental projects require both passion and precision. Kate taught them seed dispersal techniques, such as salting instead of dumping, and emphasized the importance of mimicking buffalo feet when tamping soil. Marya walked them through irrigation planning and plant selection for Houston’s brutal climate. When students struggled with technical concepts, Kate and Marya trusted these young people to rise to the complexity, and rise they did.

Simultaneously, students were courting the Resilient Cities Network. In their first meeting on July 24, 2024, Program Director Tommy Wan and Executive Director Abby Triño sat with Jordana Vasquez (Senior Manager for Climate Resilience), Kaavya Rizal (Program Coordinator), Nathaniel Echeverria (Finance Lead), Allison Ahern (Resilience Finance Team), and Katrin Bruebach (Director of Programs). R4C didn’t impose solutions but instead asked students what Alief needed and how they could support the vision. Over eighteen months of partnership, Kaavya Rizal became the students’ champion within R4C, navigating bureaucracy to ensure funding flowed when communities needed it most. Jordana Vasquez worked tirelessly to align R4C’s national priorities with Alief’s hyperlocal realities. When a second pocket prairie opportunity emerged organically, they didn’t balk at the scope change. They found additional funding because they trusted student leadership.

On April 19, 2025, the journey became tangible. Students walked the Alief Community Garden with the support and blessing of Jay and Vanessa Lipscomb from the WOW Project, who had been serving Alief’s food-insecure families for years at the historic yellow shipping container. Standing next to the yellow shipping container known as the Maldonado Space, where the WOW Project distributed food every Sunday, they envisioned transformation. Casey Sheek, the Community Garden Manager, joined them, and what could have been a simple site visit became the beginning of a deep partnership.

By May 18, students were on their hands and knees with spray paint and construction flags, mapping irrigation lines alongside Program Director Tommy Wan and volunteer Julian Nguyen. Working from initial sketches and renderings created by student artist Cassidy Wong, an architectural student at UT Austin, they plotted every pathway, every plant bed, every square foot of the 500-750 square foot installation.

June 7, 2025, brought humility and growth. The first build day didn’t go as planned. The rented sod machine from U-Haul proved unwieldy. Student leaders Lander Gonzalez, Nyelle Blount, Hai-Van Hoang, and Julian Nguyen, barely meeting the age minimum for truck rental, struggled with equipment designed for professional landscapers. But they didn’t quit. They learned. They asked for help. And help came.

Two weeks later, on June 21, 2025, magic happened. Community contractors Joseph and Joshua Birl, father and son who had watched Alief change over decades, arrived not as hired help but as invested neighbors. Suddenly, expertise met passion. The archway rose against the Houston sky. Enriched topsoil from Living Earth filled the beds. Edging went in. A weed barrier was laid. Mulch, gravel, and bricks transformed raw earth into a designed space.

But the fundamental transformation was happening in the people. Sawsan Busari and David Beckham Unaegbu from Elsik High School worked shoulder-to-shoulder with Isabelle Arusiuka, Emaan Syed, and Lander Gonzalez from Alief Early College. Bang and Minh Nguyen from the Plant Based Treaty brought their environmental advocacy and community connections. Dr. Alan Steinberg from the West Houston Association, a pillar of the business community, worked alongside Isaac Perez and Joe Garcia, grassroots community organizers. Heather Bisesti from Rice University’s School of Engineering brought academic expertise but learned just as much from the community. Eduardo Sanchez connected the work to broader justice movements through his roles with the ACLU and State Representative Ann Johnson’s office.

And presiding over it all, in spirit, was Barbara Quattro, Chair Emerita of the Alief Super Neighborhood Council, whose decades of advocacy for Alief had prepared the ground for this moment. The prairie would be dedicated to her legacy.

Throughout summer 2025, both prairies took shape with remarkable speed and community ownership. Intelligent irrigation systems were designed and installed by experts like those from Archie’s Gardening, local master naturalists who saw in these students the future of environmental stewardship. On July 19, another major build day brought Karen Loper from the International Management District to work alongside students. They installed benches designed for durability and beauty, along with educational signage created through collaboration with Houston Audubon and other conservation partners.

September 13 marked a profound milestone. The WOW Project, which had approved the original site, hosted its community outing and night market at the prairie. Families gathered on the benches. Children ran through the pathways. Elders touched the native grasses. The space was already serving as the “third place” it was meant to be, a gathering ground beyond home and work where community happens organically, where Vietnamese grandmothers share benches with Nigerian mothers, where Pakistani teens play near Congolese children.

The crescendo came on September 27, 2025. Over 50 volunteers, representing the full, beautiful spectrum of Alief’s diversity, gathered for the major planting day. Kyle Frese from Decentralized Farming LLC led workshops on growing food sustainably. Kate Unger shared National Wildlife Federation expertise about prairie ecosystems. Urban Harvest, Growing Green Thumbs, and Alabama Community Gardens brought decades of combined knowledge about native plants and community gardening.

And then they planted. 240 native Texas plants went into the ground that day: Gulf Coast Muhly grasses that would sway silver in the breeze, Texas Coneflowers in bold yellows, Aquatic Milkweed to host monarch butterflies on their epic migrations, Indian Blanket wildflowers in brilliant oranges and reds that would carpet the prairie each spring, Seaside Goldenrod, Gulf Coast Penstemon, Lyreleaf Sage. Each species was chosen not just for beauty but for ecological function.

Parents lifted children to pat down soil around plants that would outlive them all. Teenagers took photos with dirt-covered hands, posting about prairie ecology to Instagram and TikTok, making environmental justice cool. Elders sat on the new benches, watching the future literally take root in soil their community had prepared.

Perhaps the most remarkable chapter of community-driven innovation began in June 2025 at a Brays Village East Homeowners Association meeting. Board Chair Alfonso Peña and Board Member Paul Dunnand were discussing a persistent problem with their HOA members: maintenance crews kept mowing through a neglected area near the clubhouse, causing erosion, wasting resources, and creating an eyesore. The community had tried various solutions, but nothing stuck. When AliefVotes was invited to present at the meeting, residents immediately saw the connection. The same pocket prairie model that was transforming the Alief Community Garden could solve the neighborhood’s problem while adding beauty and environmental benefits.

The HOA community embraced the idea enthusiastically. Within days, Alfonso Peña and Paul Dunnand had convened additional community discussions, gathering input from residents about placement, design preferences, and maintenance responsibilities. The proposal connected directly back to those four community meetings from early 2025, where Alief residents had voted for pocket prairies as their preferred climate resilience solution. The Brays Village East community realized they could be part of this broader movement while addressing their specific neighborhood challenge.

When the Resilient Cities Network heard about this organic community opportunity, they responded with the flexibility that defined their partnership approach. Through their collaboration with Orbia, they found an additional $10,000 in funding to support this second prairie. Kaavya Rizal and Jordana Vasquez worked quickly to adjust grant timelines and budgets, understanding that authentic community organizing often means responding to opportunities as they arise rather than forcing predetermined plans onto neighborhoods.

By October 4, 2025, when the second prairie at Brays Village East held its build day, the community ownership was evident in every detail. They were signing their names on the archway, literally inscribing themselves into their neighborhood’s infrastructure. Families who had initially been skeptical about losing lawn space were now the prairie’s most prominent champions, explaining to new neighbors how the native plants would reduce their HOA’s maintenance costs while preventing erosion. The prairie wasn’t something done for them or to them. It was something they built together, with youth leadership showing them what was possible and the community making it their own.

The partnership ecosystem that made this possible reads like a directory of everyone who matters in Houston community development. Beyond the core partners already named, the network expanded to include Alief ISD Superintendent Dr. Anthony Mays and Director of Maintenance Glenn Jarrett, who saw educational opportunities in every plant. Council Member Tiffany D. Thomas and Chief of Staff Lambda Green connected city resources and political will. Leonel Resendiz, educator at Kerr/Taylor High School, integrated prairie ecology into his curriculum.

The list continues with student leaders who gave countless hours: Fernanda Santana, Perry Sharp, and Yemi Reuben, who each brought unique skills and perspectives. Volunteers like Madeline, Cindy, and Erica, whose names may not make headlines but whose hands built every pathway. Organizations like Houston Audubon Society, Coastal Prairie Conservancy, Native Plant Society of Texas, Trees for Houston, Target Hunger, Link Houston, and Houston Wilderness each contributed expertise, resources, or networks.

Suppliers became partners too. Living Earth provided soil and materials. Houston Sign Company and Signarama created educational signage. The Houston Tool Bank made equipment accessible.

In July 2025, the work received national recognition. Abby Triño and Tommy Wan traveled to Chicago for the Resilient Cities Network’s Local Roots for Resilience Conference, where they stood alongside YouthBuild Boston and other innovative community resilience projects. They weren’t presenting as students seeking validation. They were sharing expertise, offering lessons learned, proving to a national audience that the most innovative climate solutions emerge from communities themselves, especially when young people lead with authentic power. The presentation covered not just technical achievements but also the more profound truth: climate resilience cannot be separated from social justice, green infrastructure means nothing without community ownership, and youth leadership isn’t a nice addition but the essential ingredient for transformation.

What do you think helped you build your reputation within your market?

Relational organizing and the power of networks, especially in schools and youth communities, became the foundation of everything we built. Our reputation grew organically through showing up consistently where young people already gathered and proving that we were there to build with them.

The network effects were exponential. One student would invite their younger sibling to a voter registration drive. That sibling would bring friends from a different high school. Those friends would connect us with their parents who served on HOAs or worked for local businesses. Each authentic relationship created ripple effects that traditional outreach could never achieve.

What distinguished our approach was treating young people as the experts on their own lives and communities. In immigrant communities like Alief, students are often the bridges between their families and institutional systems. They’re the ones translating at doctor’s appointments, helping parents navigate school bureaucracies, explaining voter registration to their grandparents. When we centered their leadership and provided them with resources, they carried our work into spaces we could never access as outsiders.

The schools became our laboratories for democracy. When students testified about capital projects in front of the Harris County Commissioners’ court, when they facilitated community meetings in multiple languages, when they managed complex partnerships with national organizations, they were proving to their teachers, their principals, and their families that young people can lead transformational change. That credibility transferred back to AliefVotes and created a reputation for youth development that attracted new partnerships and funding opportunities.

Networks matter, but authentic networks require genuine investment in people’s success beyond your immediate organizational needs. The students who built pocket prairies with us are now studying at universities across the country, carrying lessons about community organizing into new contexts. They’re our best ambassadors because they know we invested in their growth, not just their labor.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://aliefvotes.org

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aliefvotes/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100088601864118

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/aliefvotes/

- Twitter: https://x.com/AliefVotes