We were lucky to catch up with Sayako Hiroi recently and have shared our conversation below.

Sayako, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Do you wish you had started sooner?

If I could go back in time, I would not have wanted to start my creative career any sooner or later than I did. My path was not linear. I studied ethics in Tokyo, then spent four years working in sales and marketing at a manufacturing company. At the time, I often wondered if I was drifting away from what truly mattered to me. But those years taught me something essential: the discipline of listening, the patience of waiting, and the contradictions within human choice.

When the pandemic forced me to pause, I finally turned toward the voice I had long buried beneath the demands for productivity and efficiency, a voice I had silenced since childhood. It was painting. Moving to the United States to pursue an MFA was no longer a career decision but a choice to face myself rather than society. Had I begun earlier, I might have lacked the life experience necessary to sustain this urgency. Had I waited longer, I might have lost the momentum to act.

So I began exactly when I needed to. Not because the timing was perfect, but because imperfection, the delay, the detour, and the rupture were the very conditions that made my practice possible.

Sayako, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

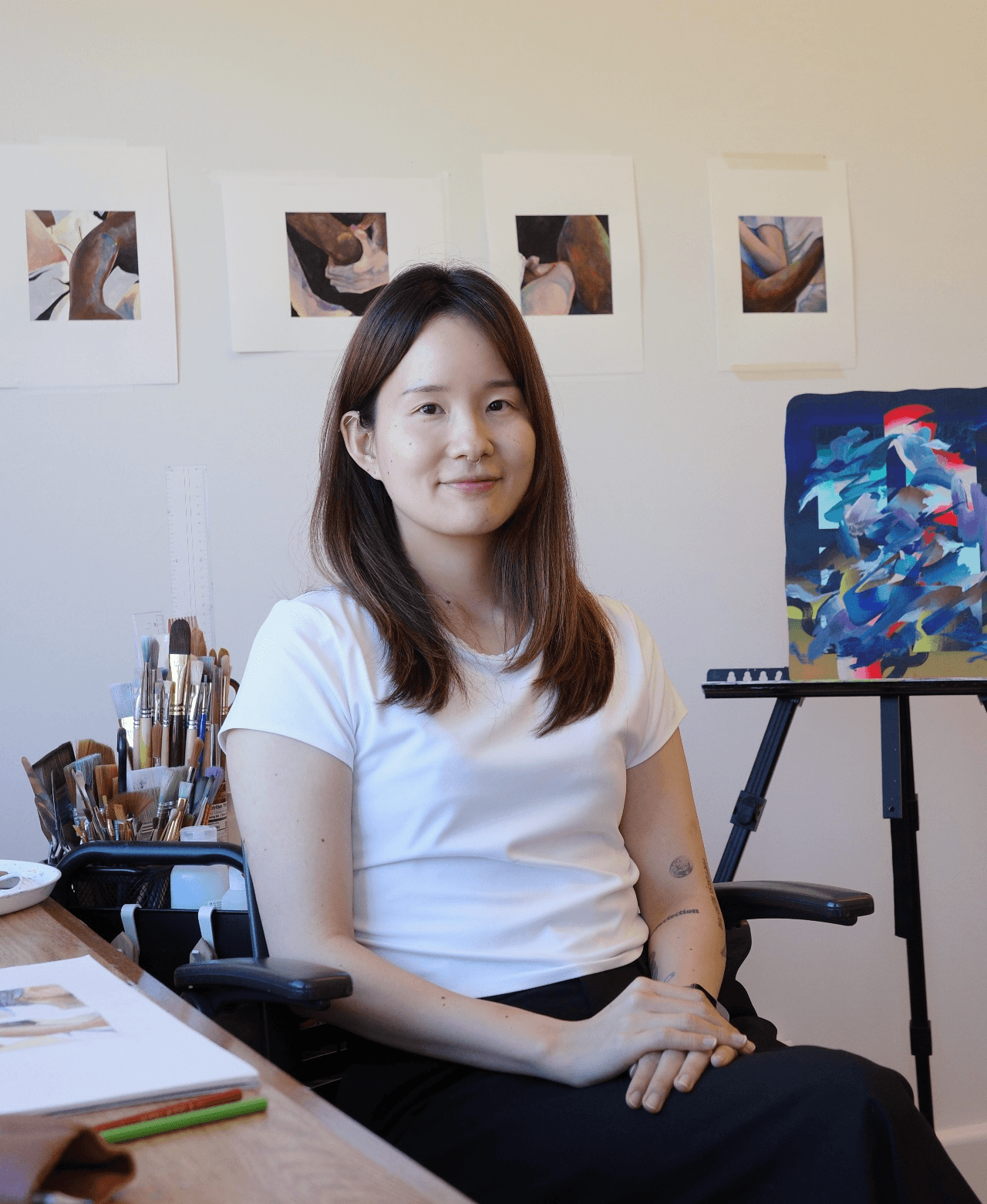

I am a painter and a kintsugi artist, originally from Tokyo and now based in Boston. My path was not straightforward. I studied ethics at university and worked for several years in sales and marketing before returning to what I had loved since childhood: painting and traditional craft. Those experiences shaped how I continue to inform my practice today. They gave me a sensitivity to human relationships and to the way systems shape our inner and outer worlds.

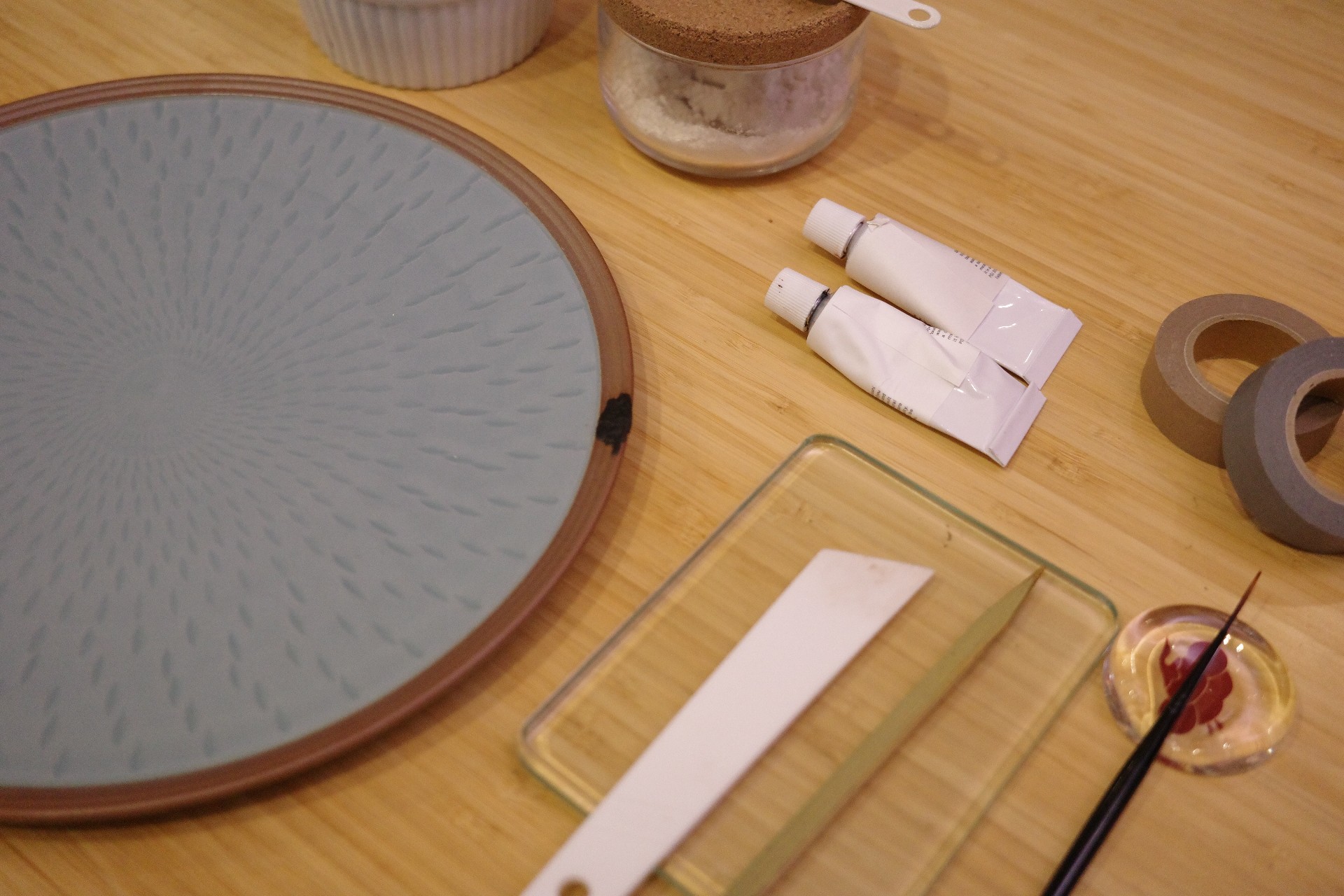

In my kintsugi practice, I repair broken ceramics using traditional Japanese lacquer and gold. What I offer is more than restoration. Clients come to me with cherished objects that carry memory, loss, or attachment. By repairing them, I help preserve both function and story. What sets me apart is not only technical skill but the way I frame kintsugi as an act of care, an ethical response to breakage rather than a simple repair.

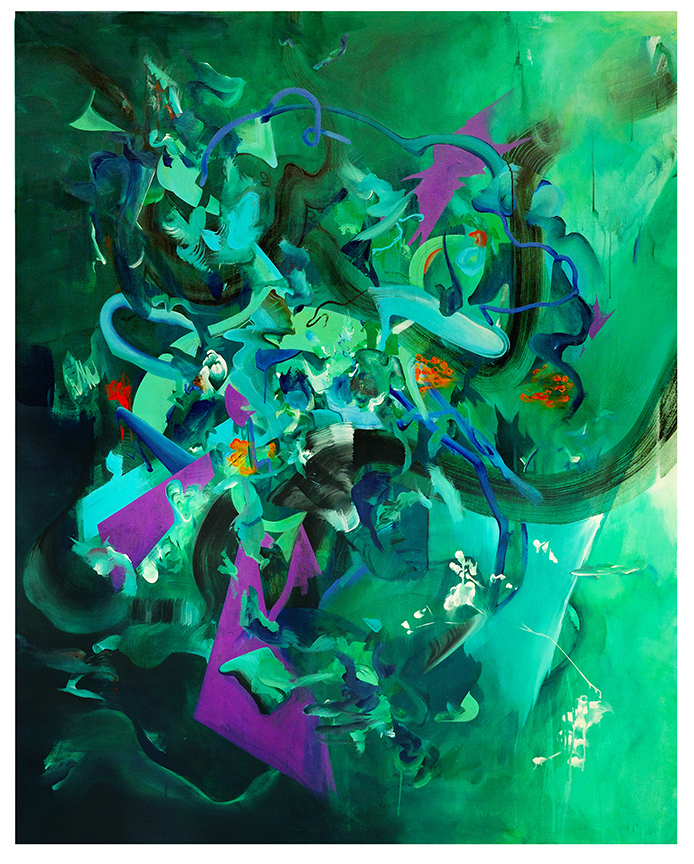

In my painting practice, I work from the history of bijin-ga (Japanese woodblock prints of beautiful women) and reimagine them in dialogue with women whose voices were silenced in history. I chose an abstract language in these works because I did not want to rely on the visual power of Japan that ukiyo-e prints have long represented. Through abstraction, I wanted to move away from the surface-level fascination with oriental beauty and instead unravel those images to paint what lies beneath: silence and the unseen.

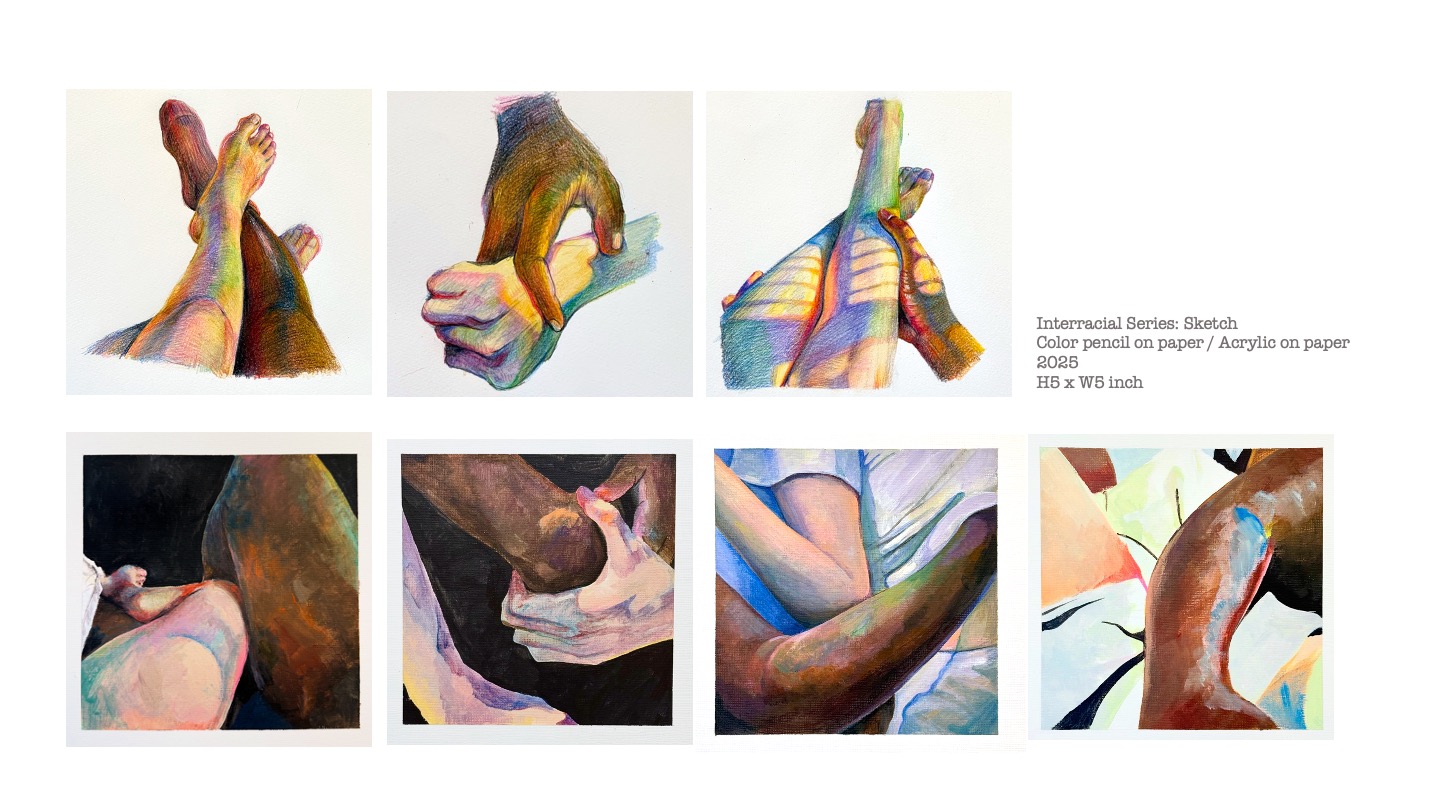

My most recent series takes a different direction. Here I paint interracial relationships, drawing from my own experience as a Japanese woman in America. In this series, I aim not to depict strangeness or difference as spectacle, but to portray the tenderness and universality that exist within all forms of human connection such as love, safety, and belonging. I also look closely at the difficulty and beauty of intimacy that transcends difference.

What I am most proud of is that my work refuses to separate the personal from the ethical. Whether I am repairing a bowl or painting on canvas, my practice begins with listening, listening to what has been broken, erased, or overlooked, and responding with presence rather than possession. For anyone encountering my work or practice for the first time, I want them to know this: I do not see art as decoration or luxury, but as an ongoing dialogue with care, history, and unseen traces.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

When people speak of resilience, they often imagine strength as endurance, the ability to stand firm against pressure. For me, resilience has always been quieter. It was the decision to leave a stable career in Tokyo during the pandemic, to cross the ocean without certainty, and to begin again.

Those years of transition were not glamorous. I worked in unfamiliar languages, doubted myself deeply, and felt invisible at times. Yet resilience was not the absence of fragility, but the willingness to live with it, to let it transform into another form of strength. Every hesitant brushstroke carries the memory of rupture. What I have learned is that resilience is not the opposite of fragility; it is the capacity to stay with what feels uncertain and allow it to evolve into something enduring.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

What many people outside the arts may struggle to understand is that a creative life is not built on clear answers or fixed goals. The world often asks us to choose: success or failure, beauty or ugliness, conservative or liberal. Yet my practice lives in the space between such binaries. Meaning emerges not from certainty but from staying within the in-between.

Another common misunderstanding is the role of care. Many assume care is private or sentimental, but to me, it is the courage to remain with what has been forgotten or silenced, and to resist erasure through presence. Whether in painting or kintsugi, care is not a gesture of softness. It is a steady form of attention to what remains unseen.

If there is one insight I would offer, it is this: art is not the opposite of life, nor its embellishment. It is one way of remaining present within its fractures.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.sayakohiroi.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/sayakohiroi

- Other: Substack: https://sayakohiroi.substack.com/