We were lucky to catch up with Beki Song recently and have shared our conversation below.

Beki , looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

Most of the projects I’ve worked on so far have been solo exhibitions that came from a deeply personal place.

In those shows, I explored emotions like love, fear, obsession, and vulnerability through sculptural beings I call wild babies. These figures exist somewhere between humanity and monstrosity—they reveal the complexity of love and the uneasy beauty hidden in emotional fragility. Each project I worked on helped me understand myself a little more and grow, not only as an artist but as a person.

But over time, I began to feel the urge to move beyond my own inner world—to connect with ideas and communities larger than myself. That’s why the projects I’m currently working on have become especially meaningful to me.

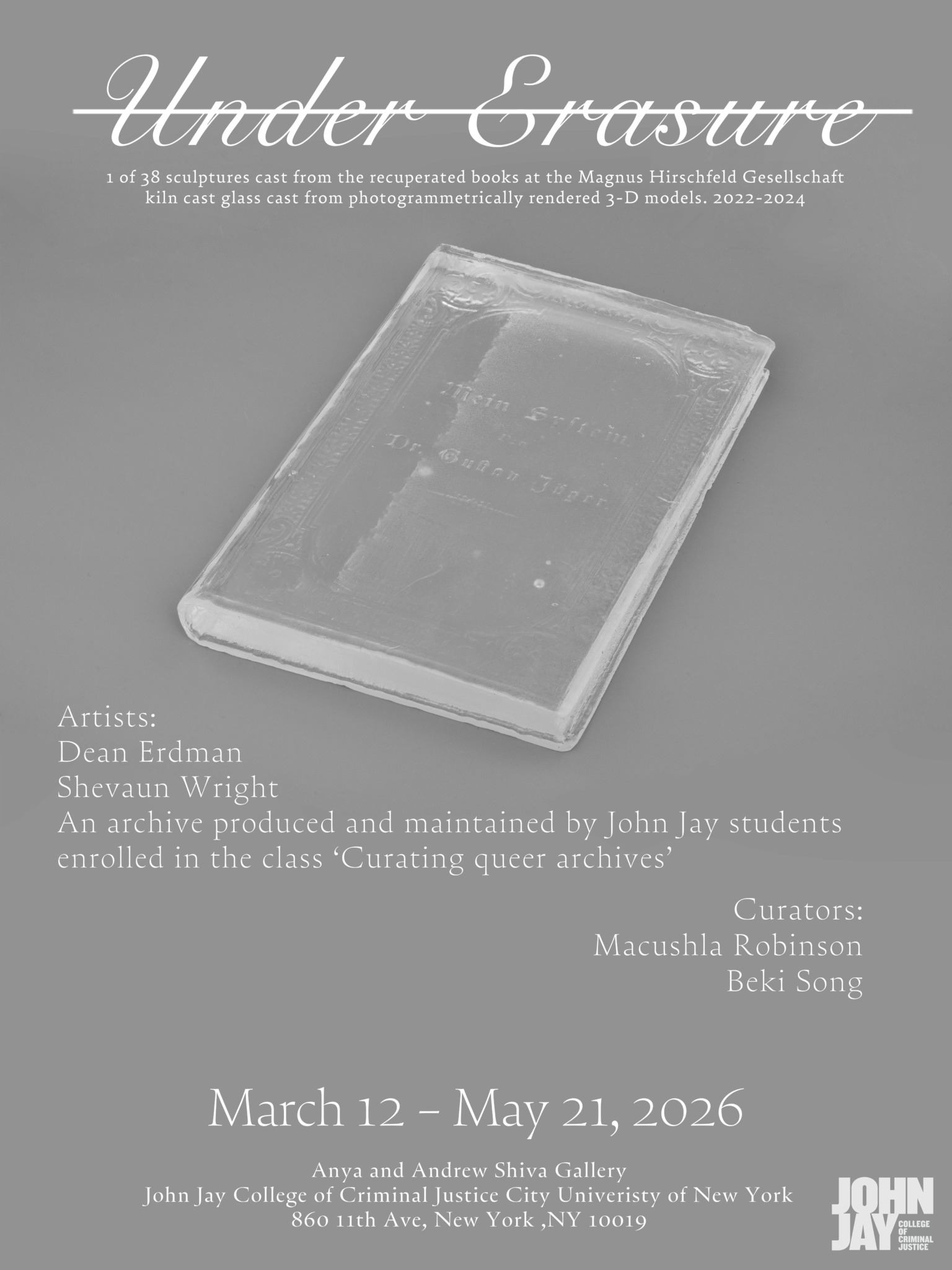

The first is Under Erasure, an exhibition I’m co-curating with Macushla Robinson at the Anya and Andrew Shiva Gallery, which will run from March 12 to May 21, 2026. The show centers on queer archives—histories and memories that have been erased, censored, or forgotten—and explores the quiet acts of care and recovery that keep them alive. Working on this project has allowed me to translate the themes I’ve long explored in sculpture—vulnerability, love, and repair—into a curatorial form that engages with collective memory and resistance.

At the same time, I’m also preparing another project under the curatorship of Achia Anzi, which explores the history of Jewish religion, the Talmud, and its influence on Korea. This exhibition examines how spiritual and philosophical ideas travel, evolve, and reappear across cultures—something I find deeply resonant as an artist working between East and West.

Through these projects, I’ve realized that curating, like art-making, can also be an act of empathy and reflection. It’s about creating spaces where tenderness becomes a form of strength, and where stories—both personal and political—can coexist. Moving forward, I plan to continue developing projects that bridge my sculptural practice and curatorial work, expanding from the emotional to the social, and continuing to build spaces of quiet repair and remembrance.

Beki , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

My name is Beki Song, and I’m a Korean artist based in New York.

I create sculptural beings I call wild babies, creatures that exist somewhere between humanity and monstrosity. They embody the complexity of love and the fragile emotions we often try to hide, such as longing, fear, dependency, and tenderness.

My practice began as a deeply personal attempt to understand emotions that felt too overwhelming to express in words. Over time, I realized that what started as an inward search was also a way to connect with others. People often told me that my sculptures felt strangely familiar, as if they were encountering a reflection of themselves. That helped me understand that art can be both intimate and shared. Through my own vulnerability, others could recognize their own.

I work primarily with clay, plaster, synthetic hair, and paint, using tactile processes that mirror the messiness and rawness of human feeling. My installations often resemble psychological landscapes, inviting viewers to enter rather than simply observe.

What sets my work apart is its emotional sincerity. I’m not interested in polished perfection; I want my sculptures to feel alive and to breathe imperfection and emotion. My art lives at the intersection of beauty and discomfort, where tenderness becomes a quiet form of strength.

Beyond sculpture, I have been expanding into curatorial practice, developing exhibitions that explore memory, repair, and the politics of absence. Whether through my own work or collaborative projects, I am drawn to creating spaces where empathy and reflection can take shape. For me, being sensitive in a world that often demands hardness is a radical act.

Ultimately, I hope my work encourages people to look inward with compassion. Vulnerability is not weakness; it is the beginning of understanding and healing.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

Art may not always look grand in the beginning, but I believe it is a lifelong journey of learning and growth. Every artist starts small. What matters is not early fame or recognition, but the persistence to keep creating, even when no one is watching.

Being an artist means building something slowly, step by step. Each project, each attempt, and each small improvement becomes a foundation for the next. I know that what I’m doing now might seem modest, but art has its own rhythm. With time, with resilience, and with the right people around me, I believe it can grow into something meaningful and lasting.

What has truly sustained me is not financial help, but the emotional support of people who genuinely care. They believe in me when I begin to doubt myself, listen when I feel lost, and give honest advice when I need perspective. Because of them, I’ve learned that I don’t have to carry everything alone.

Art can be a lonely path, but real resilience isn’t about never falling. It’s about continuing with an open heart, trusting in the process, and allowing yourself to be lifted again by the people who stand by you. That quiet faith—the combination of perseverance, learning, and human connection—is what keeps me moving forward as an artist. And that, I believe, is how small beginnings eventually grow into something larger than anyone can predict.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

I think the best way society can support artists is by understanding that creativity takes time, care, and patience. Art doesn’t always produce immediate results or visible success, but it grows quietly through experimentation, failure, and persistence. What artists need most is not constant pressure to succeed, but the freedom to keep trying, learning, and evolving.

Financial resources are, of course, important—but emotional, educational, and institutional support are just as essential. Mentorship programs, accessible workspaces, and fair opportunities for emerging artists can make an enormous difference. So can communities that genuinely value creative labor, not just its marketable outcome.

Artists also need to feel seen and respected as people, not just producers of culture. Many of us work in solitude, facing uncertainty every day. A thriving creative ecosystem is one that allows space for vulnerability and experimentation, where artists are encouraged to take risks without fear of being forgotten.

In the end, supporting art means believing in its long-term impact—investing not only in what is already visible, but also in what is still becoming. When society values process as much as product, it creates room for genuine growth, and that’s when creativity truly thrives.