We were lucky to catch up with Jay Thomas, Ed.D. recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Jay thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

I spent thirty years in education, the last twenty of which were as a professor of education at Aurora University outside of Chicago. My areas of research and teaching were in learning theory, motivation, and research methods. I had published several textbooks, many book chapters, and numerous articles related to my teaching and research, but toward the end of my career, I decided to begin writing about things that interested me outside the classroom, in particular the ways in which learning and teaching and motivation in the development of athletes and artists.

I grew up in and around professional sports, primarily baseball and tennis, and I had a good understanding of what it required to reach the highest levels of performance in those areas. But what about athletes who pursued other interest and avocations following their playing careers? This question led me to an article in which I interviewed three professional baseball players who became distinguished artists following their playing careers.

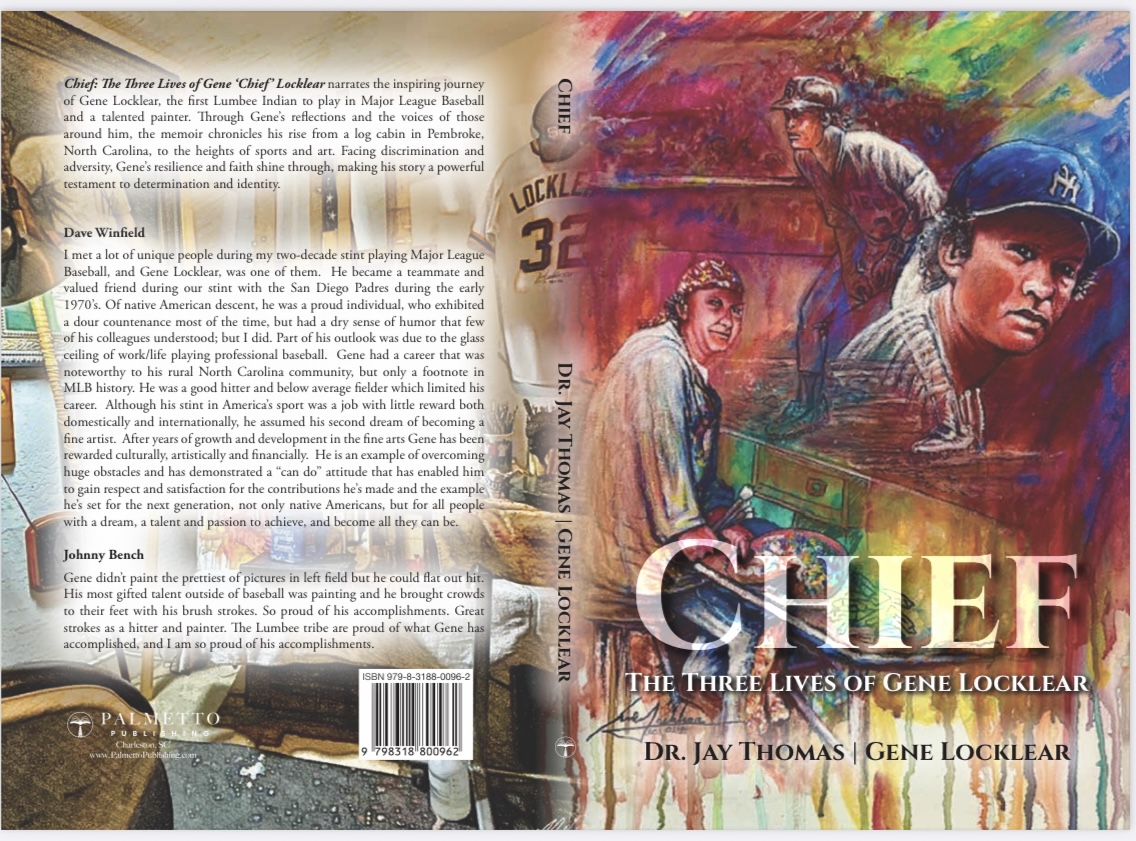

One of the artists I captured in the article, Gene Locklear, spent five years in Major League Baseball. Following his playing career, Gene became a very distinguished artist of Native American life, rural America, and professional sports. His paintings have hung in the White House, the Pentagon, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

My wife Gina and I became close friends with Gene and his wife Susan, and on a trip to Arizona with my family, I cautiously approached him about writing his life story. I had never written a biography before, and I could not have imagined the richness of Gene’s life when I undertook this professional risk. It became nearly a four-year, unpaid project with no assurance that it would be published or that it would in the end make any money.

The book, titled Chief: The Three Lives of Gene Locklear, will be published in the fall of 2025. I could not have imagined the number of friendships, relationships, and professional opportunities that this book would create for me. I guess I can call myself a professor, a biographer, and now a businessman.

Jay, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

The short answer, I suppose, is that I wanted to grow up to be either a college professor or a baseball player. Genetics kept me from a big league career, but I turned my teaching and research into pursuits that allowed me to work closely with people whose skills took them to the highest levels.

My dissertation chair, Dr. Jennifer Schmidt, had been a college athlete who studied motivation and resilience. Her research on motivation, which included the concept of flow, led me to ask questions about talent development, expertise, and resilience.

It turned out to be a very fortunate confluence of experiences. In my background research on Gene Locklear, I met quite a few former athletes who talked quite candidly about becoming a professional painter, writer, or sculptor. Along the way, I reconnected with former pitcher John D’Acquisto, who had a lengthy big league career and who has since become a distinguished artist.

John taught me quite a bit about the development of artistic skill and technique, and along the way, we began discussing just what is necessary for elite performance in sports and art. We began dabbling in the biomechanics and psychology of pitching.

This “playing in the sandbox” led John and me to a momentous decision. We created a 14-dimensional model of the ideal pitching motion. This model borrowed from John’s perspective drawing and our knowledge of pitching.

This model is now the centerpiece of our new company Kinetic Force Analysis, which melds art, body, and psychology.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

I used to tell my friends that I could wallpaper my house with rejection letters — academic jobs, articles, books, book chapters. Any rejection stings a little bit, even after thirty years in teaching and writing. But over time, you realize that your writing might not be a good fit for a certain publication or that your project might not align with the current market. Or, sometimes, the person who reviewed your work might have skipped their morning coffee. I remember one of my early submissions came back with this comment: “You call this a research proposal!?”

I’ve learned that rejections are both constructive and motivating. Very often, I received comments that began, “We like your work, but you might consider developing this section of your research a bit further.” I never let a rejection sit on my desk for more than a week. I take the recommendations from the rejection letter, make some adjustments, and send it off again. Any rejection letter informs my future submissions.

Can you tell us the story behind how you met your business partner?

How I met my business partner. . . the answer is that it unfolded in a strange and fortunate way. In the early 1980s, I worked at Wrigley Field in Chicago as a batboy and clubhouse attendant (in other words, I washed lots of dirty uniforms and polished shoes.) John D’Acquisto was a pitcher for the San Diego Padres and was the first player I met on my first day on the job.

Forty years later, when I started my research on Gene, I reached out to John, who knows Gene as a player and an artist. Our discussions were pretty far flung, from art to baseball to history to physics to biomechanics, and we became very close friends. John had taken a class at Harvard on computer programming, and we began applying his doctorate in biomechanical engineering with mine in educational psychology to create profiles of individual players that could point to potential injuries, particularly among pitchers. We began comparing our reports to what was actually happening on the field, and we found that our reports were reliable and accurate.

We founded our company, Kinetic Force Analysis, on the premise of preventing injuries, particularly among younger pitchers, who are at a particular developmental risk. I think this new endeavor allows me to keep teaching, which is what I am at heart.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.drjaythomas.com

- Linkedin: Jay Thomas, Ed.D.

Image Credits

Photo credits Jay Thomas