We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Joyce Huang a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Joyce thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Do you think your parents have had a meaningful impact on you and your journey?

Many things, the first of which is uprooting our family and flying us all to Canada over ten years ago. And I do mean “uproot” with the negative connotation implied: immigration was a difficult move when you’re relying on two kids, ages ten and eight (my older sister and me respectively), to translate—our parents did not speak English. There were translators for the most obviously formidable tasks, like going through customs and finding housing. But the rest we had to weather through with my sister’s and my meager grasp of English, and what (large) gaps remained in our vocabulary, we patched up with Google Translate. The thing about living in a country that does not speak your language is that it really humbles you, finding that you are no longer the target audience of every ad on the roadside, that this world is no longer built for you and in a shape you understand intuitively. You do not realize how privileged it is to be able to learn, shop, small talk, do every seemingly mundane and simple task in your mother tongue—until you’re really thrown out there, filling out school safety forms with zero idea what half the abbreviations on there stand for, or trying to buy snow tires when you’re from a city that never snows.

Of course, I can’t forget the bilingualism that also came as a definite benefit. Having two languages warring in my head was my anthem and lullaby growing up, and what spurred my interest in language. I saw somewhere that R. F. Kuang (the author of Yellowface and Babel) said that Chinese is a language in four-four meter—a beautiful metaphor, because of Chinese’s tendency to build idioms in four characters and hence four syllables. My parents insisted that I continue to take Chinese lessons, that I’d spend enough time speaking the language so that I’d dream in Mandarin. They taught me to find the rhythm, the heartbeats of Chinese, and my English-speaking environment around me allowed me to learn a whole other set of drumbeats, a whole other song. That was a lot of metaphor, but to put it simply, I would not be able to write what I write without these two languages and their accompanying two sets of culture, literature, and mythology, and I would not have had these if not for my parents’ upbringing.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I’m a full-time student studying Classics at Oxford, and I have to say that mythology–which has a lot to do with what I study–is a big influence on what I write. I’ve had this dream ever since elementary that I’d be a writer, and I’ve been typing up mini stories since grade four or five, but I didn’t start getting into poetry or submitting to magazines until high school. That was when I joined a literary arts journal, went to the Iowa Young Writers’ Studio, subscribed to the Poetry Foundation’s poem of the day, and admittedly quite enjoyed the part of university applications that involved a lot of writing and self-exploration.

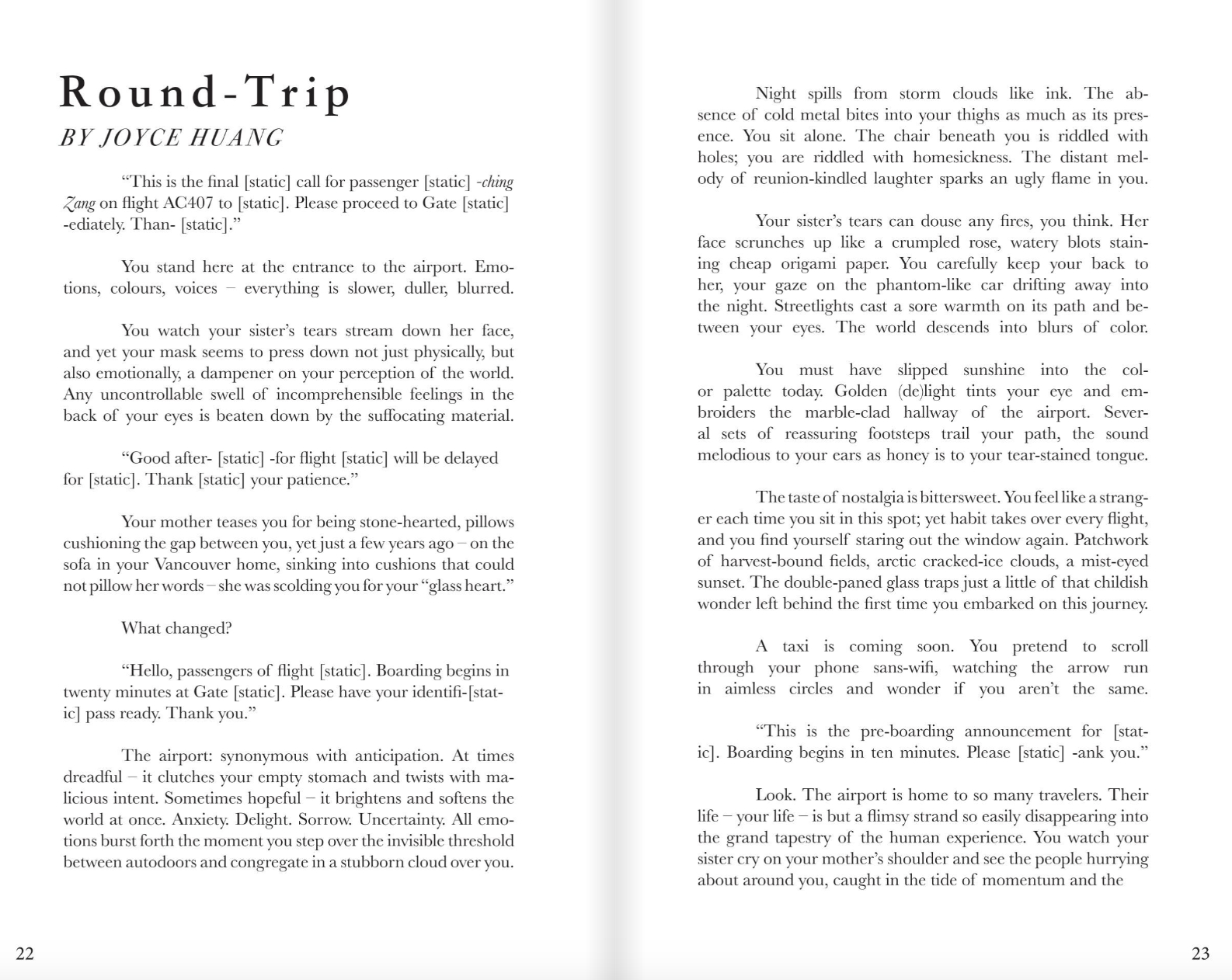

As I mentioned earlier, my interest in writing is very much stimulated by my bilingual environment growing up, and so what I write (creative nonfiction, short stories, poems) often touch on themes related to language, to the experience of immigration, to mythology both Chinese and of course Greek and Roman, and also to feminism. “Period.”, a creative nonfiction piece I wrote and published in The Lumiere Review, was inspired by recent Chinese feminist movements online addressing period-stigma, particularly sexist superstitions that forbid women on their periods from visiting family graves or sitting on tool/camera boxes for films. As you can see, even though I write in English, a lot of my ideas and inspirations, and even my style sometimes draw from my Chinese roots. I learned at a workshop once to always write what only I could have written, and I’ve tried to follow this rule ever since. Although I do also think that what one writes is always informed by who they are and it’s something they cannot escape from, a limit on the one hand but also a kind of signature. As a writer, I also like exploring different mediums and styles: I created a mini digital writing collection and coded a website to display my short stories, in such a way that the digital format might enhance the message or contribute to the impact of my writing.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

“Invisible Women” is a book on statistics and how women have largely been overlooked in collecting and using data—both historically and even now. It’s prompted me to think a lot more on how it is a systemic thing, how everything women do and need are seen as less important and straying from normal, and how this bias is shown in so many different things, from the order snow is plowed to the space put into bathrooms for each gender to how women are more likely to be at risk of unemployment and poverty because of hiring biases. This all sounds so very over-emphasized and like something already well-argued twenty years ago, and yet somehow there are so much more of this slipping under our radar and happening right in sight–what we think is happening is not nearly enough to account for the amount of actual prejudice taking place, and the amount of deaths and suffering that could have been prevented. This book really helped put into reference the abstract sense of prejudice, and put into reality what exact impacts it could have, small and big, on our daily lives–and that is not even accounting for the other kinds of prejudice we know is also very much present in our system. This doesn’t necessarily seem related to creative writing, which is what I do, but really has everything to do with it, because I definitely believe that any form of art is political and sends across a message: art is not art if it does not discomfits the audience and makes them feel something. So this book and what it’s taught me has a recurring influence on how I think and the messages I want to convey in writing.

This second book does not have an English translation: extremely digestible and easy to pick up at any time, it is a collection of letters exchanged between Japanese feminist Chizuko Ueno and artist Eiko Tabusa, whose title approximately translates to “Feminism From Square Zero” or “Feminism From Scratch.” If “Invisible Women” gives you a lot of problems that need to be dealt with and not much you can do, this book tells us–not exactly how to solve them, but some very applicable conceptions of feminism and lots of food for thought, and most importantly what we realistically can do as feminists. Ueno and Tabusa give a very loose–in a way I think necessary–definition of a feminist, and allow that you make mistakes and be unintentionally misogynistic sometimes and make mistakes, and asks that you also be forgiving of others. The title itself doesn’t just indicate how accessible the authors have made feminism in their writing–which they have–but also how feminist thoughts are rarely formally taught in schools and often experience a gap when passing down from one generation to the next, and so often every generation must go through the same process of developing their feminist ideology “from scratch”: they are not standing on the shoulders of their predecessors, because their predecessors were lost to time, lost to being the atypical, neglected second sex. What Ueno and Tabusa ask the feminist reader to do is also something that can realistically be tackled and is kind of built on an alternate interpretation of the slogan “the personal is political”: that one tries to change oneself first, and one’s partner, family, the “personal”. To change how one sees the world, one person, one family at a time. I’ve been trying to do the very same after reading this, to change how I think and to try to bridge the gaps in feminist knowledge, to incorporate their thinking into mine so as to not start my journey from “square zero.”

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I’ve always had this habit of looking to others for approval, because growing up I’ve always been a really well-behaved, straight-A’s kid who never speaks out of turn or had a rebellious phase. So it’s hard not to keep turning to authority figures to fish praise from, and to keep from floundering when I don’t have someone to tell me whether the decision I’m making is the right one. It’s hard to gauge whether I do what I do because I want to, or because I’ve been told to, or because I’ve simply grown used to doing it. This was particularly hard when I was applying to college because that was when I really needed things figured out, but also it’s not necessarily realistic to expect a seventeen-year-old to have her life figured out, to know exactly what she wants her life’s path to be, and whether she’s ready to risk a potentially unstable career that she thinks she’d like, over a more financially rewarding job that sounds a little soul-drying. And she’s not even sure if she knows what’s her major. But the college application season has a way of forcing you to get everything figured out. There were endless arguments and discussions with my parents and university counsellor and best friend on whether I am really applying first and foremost as a Classics major, am I giving up Computer Science entirely, why can’t I apply to that university instead of this, is that topic for my essay really a good choice, etc etc. I managed to convince a lot of people what I want to do, and to be honest sometimes I was trying to convince myself. But I think all those application essay writing was useful after all, because it did make me realize that I truly cannot write what I do not believe in, that it is harder to lie in Times New Roman, 12 point font, double-spaced, than it is in a dinner conversation. Because I cannot fake the way I live through words; I can’t fake my heartbeat. I can’t write about programming or economics, the same way I write about language. The difference is palpable.

So I chose Classics, because if nothing else, my writing’s convinced me that this is what I truly love. I can’t deny that I still do live off of praise and approval, but I think I’ve learned (or unlearned) that it’s hard to lie to yourself, and even harder to live such a lie. That no matter how much I want to do exactly what others want me to, to be given approval for my every move, they can’t pen my life, so I can’t let them pilot. So now whenever I’m in doubt, or need to vent, I pick up a pen and let my writing be my answer.

Contact Info: