We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Val Yang. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Val below.

Val, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

One of the biggest risks I’ve taken was claiming myself as an artist.

Even though I trained in the arts for years, it still felt impossible to say out loud that I wanted to make art on my own terms—telling my stories instead of other people’s, working for myself instead of being safely employed. My parents are both hardworking people from a small town in China, where stability and modesty are prized. Growing up, even eating out at a restaurant or buying a new shirt felt like an indulgence. So when someone like me says, “I want to be an artist,” it can sound like a luxury, even a sign of delusion. The fear of seeming irresponsible or entitled kept me from fully stepping into that identity for a long time.

But when I was accepted into my first artist residency—a bioart program at SVA—I knew I had to make a leap. On the very same day the residency began, I was let go from my full-time design job. I didn’t even have time to process the job loss because I was too excited to dive in. For the first time, my days were filled with making, experimenting, and simply following my curiosity. It was terrifying. But I also felt more alive than I had in years.

At the end of that month, sharing my work with fellow residents and critics, I felt truly seen as an artist. That experience shifted everything. I’m now working on fermentation and dining-based art experiences that bring people together to talk about food, memory, and culture. My life is less rigid now, but it’s fuller—of risk, yes, but also of purpose. And I am here for it.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

My name is Val Yang, and I’m an artist and designer working across disciplines—ranging from bioart and creative technology to interaction and visual design. My creative practice is rooted in storytelling through materials, systems, and sensory experiences. I grew up in a small town in China, later trained as a designer in the U.S., and now navigate both worlds in my work. I often think of myself as a translator—between cultures, technologies, disciplines, and species.

What drives my creative work is a sense of responsibility to the stories that often go untold—the ones passed down in kitchens, held quietly in the body, or dismissed as unscientific or irrelevant. I’m particularly focused on exploring how knowledge is preserved and transferred—not just through language or code, but through recipes, rituals, and care-based labor.

Much of my recent work investigates microbial life and fermentation as both material and metaphor. I see microbes as collaborators. They ferment, decompose, and transform. They remind me that decay can be fertile and that invisibility doesn’t mean insignificance. These concepts help me reflect on cultural memory, migration, and the slow, quiet forms of power carried by women and marginalized communities.

I’m inspired by bioart, indigenous science, feminist theory, and interface design—and by my own lived contradictions: someone trained in Western design systems but raised with Eastern sensibilities; someone who values precision but seeks wildness. I’m drawn to the semi-feral—things that exist between domestication and wildness, structure and intuition.

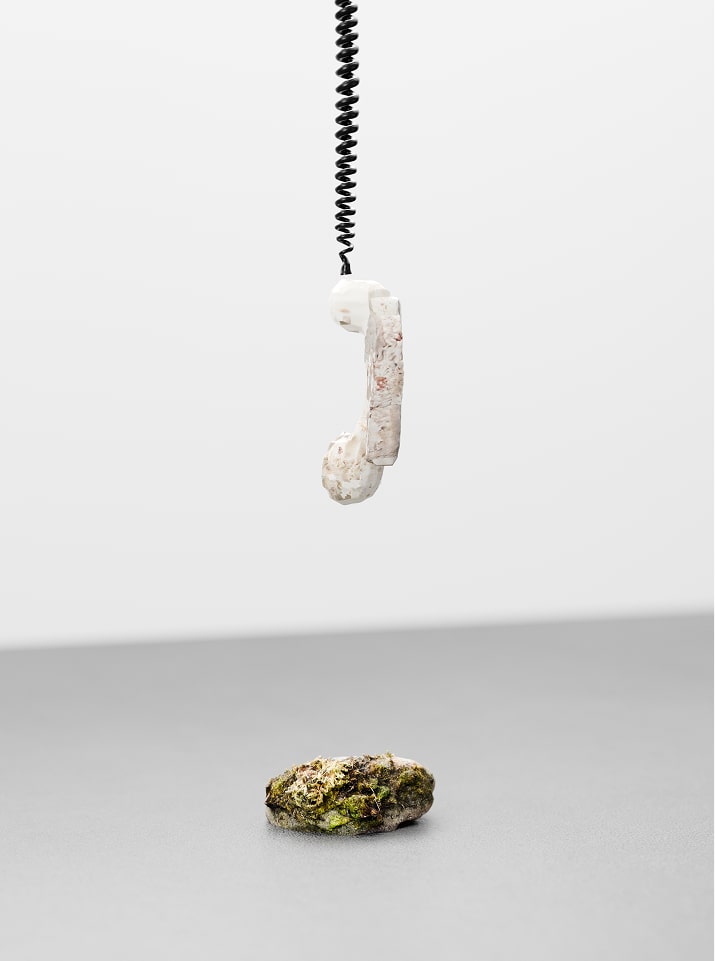

My creative practice is anchored by a body of works that explore microbial life, care-based labor, and cross-species communication. Each piece begins with a question—often about memory, ancestry, or the systems that shape our understanding of knowledge and worth. I use sculpture, performance, sound, fermentation, and AI to construct spaces that feel both intimate and speculative.

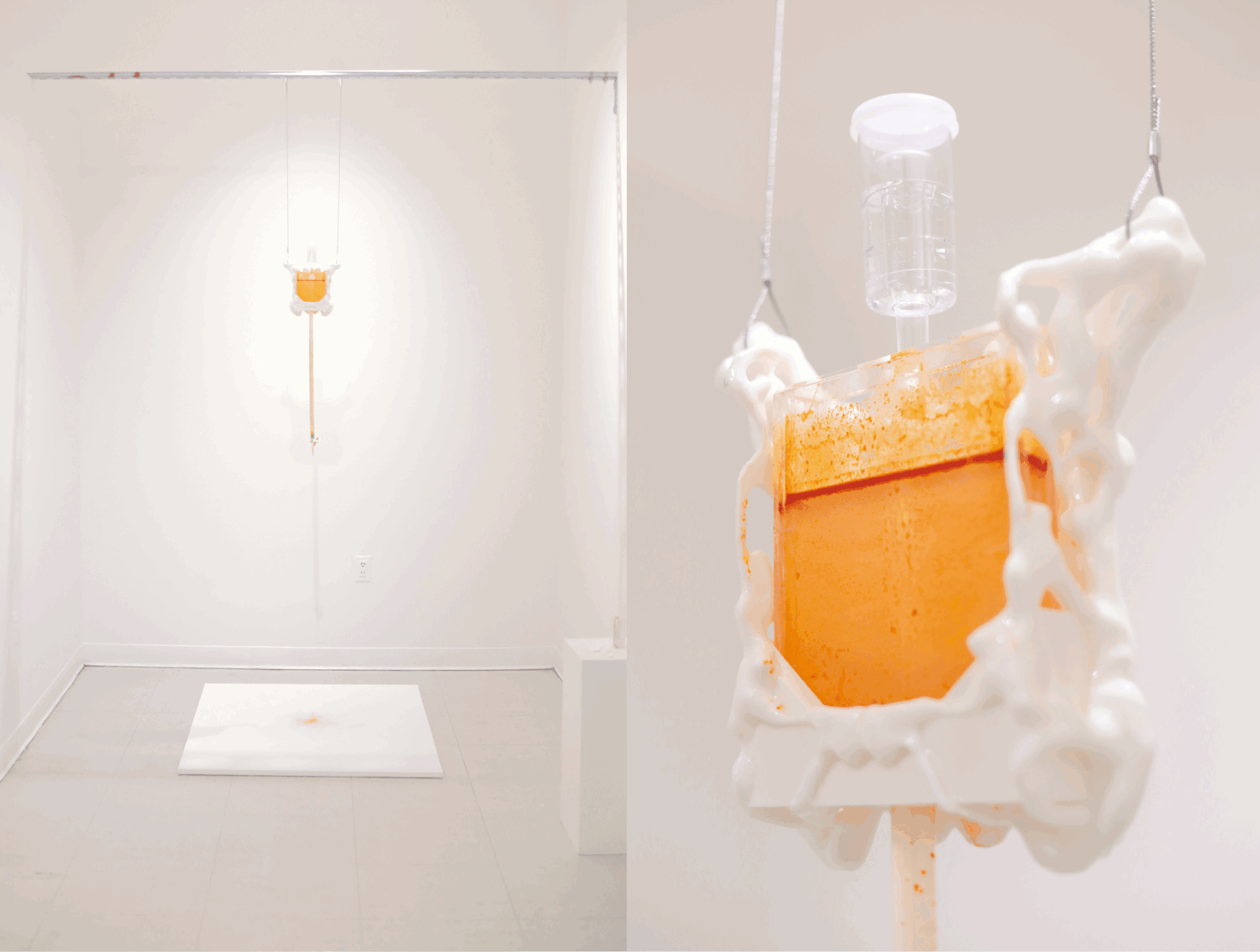

Semi-Feral is a multipart series that began with fermentation. Drawing on the traditions of suantang (酸汤), a sour soup made with cherry tomatoes and sticky rice, this project reclaims fermentation as a form of resistance, transformation, and intergenerational knowledge transfer. The sculptures in Semi-Feral act as both vessels and living systems—embodying a push against the domestication of identity and creativity.

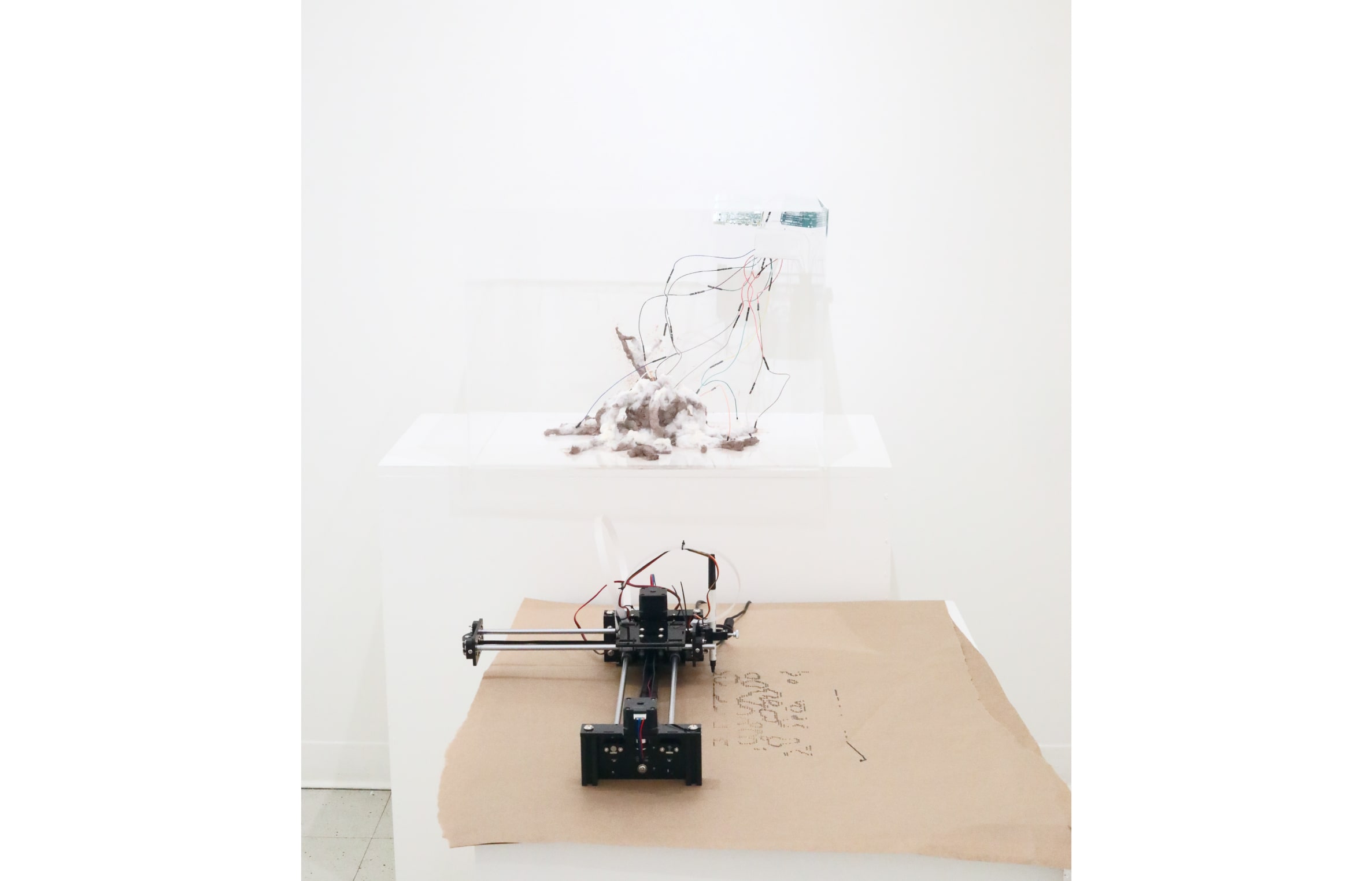

In 1,000 Threads and 10,000 Strands, I translate bio-signals and microbial data into performative systems that respond to human presence. This project investigates the possibilities of mutual intelligibility across species and intelligences. I ask: What does it mean to communicate with something you can’t see or fully understand? The result is a series of responsive sculptures and sound-based interactions rooted in trust, ambiguity, and collaboration.

Fleshbook is a living archive of layered kombucha “leather” pages, bound and rebound over time as the material evolves. It speaks to the body, memory, and cyclical transformation—a book that grows, heals, and sometimes decomposes.

Mycophone is an earlier sound-based project where mushroom signals are sonified through sensors, allowing fungi to “speak” through sound. This work emerged from my curiosity about the quiet intelligence of mycelium and how we might attune ourselves to its rhythms.

Together, these works form a constellation of themes I return to often: the porousness of boundaries, the agency of nonhuman collaborators, and the political power of slowness, softness, and care. At the heart of my practice is the belief that making is a form of listening. I want my work to create moments of connection—between people, disciplines, and ways of knowing—that feel generous, intimate, and transformative.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

One thing I think non-creatives often don’t see is how much invisible research, context, and cross-disciplinary learning feeds into creative work—especially in a practice like mine. I didn’t arrive at my ideas by following a single path. I study microbiology, interface design, fermentation, data, feminist theory, indigenous science—because all of those worlds inform how I create. My work might look like a sculpture, a recipe, or a sensory experience, but beneath it are layers of scientific processes, cultural history, and personal memory.

Sometimes people look at the final output and ask, “What is it?” And I get that—it can be a lot to look at at first. But creativity, for me, is beyond decoration or entertainment. It’s about building new ways of thinking and feeling. It requires time, slowness, and sometimes context you might not immediately have. I think people are used to consuming content quickly—but creative work often dance with that speed. It asks you to sit with it, ask questions, maybe even feel confused for a moment. That’s part of the process.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

I think one of the biggest issues is that art still isn’t made accessible enough—for artists or for the public. Too often, it’s treated as something elite, locked behind institutions, or only for people with certain types of education, money, or connections. But creativity is part of being human. Everyone deserves access to the space, time, and resources to explore and express that.

To support a thriving creative ecosystem, we need to make sure artists—especially those from underrepresented backgrounds—can actually afford to keep making work. That means more public funding, more low-barrier grants, affordable studios, and platforms that don’t just favor who’s already visible. Not everything needs to be polished or market-ready to have value. Process, experimentation, failure—those all deserve support too.

We also need to rethink who art is for. It shouldn’t only live in galleries or behind paywalls. It should be in schools, on the streets, in community kitchens and science labs. We should be encouraging more overlap between art and everyday life—not asking artists to isolate themselves into silos or produce work that fits neatly into institutional expectations.

Supporting artists means trusting them, and believing that creative work isn’t a luxury—it’s a necessity. It’s how we make sense of the world, ask questions, and imagine something better.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://valyang.xyz

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/oxueyo/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/val-yang-19a9051b4

Image Credits

Image Credits: Val Xueyi Yang