We were lucky to catch up with Abby Webster recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Abby, thanks for joining us today. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

Performing my songs is one of the only times I feel truly seen. I think that’s what keeps me coming back. In those moments, all the fragmented parts of me converge into one powerful force.

I don’t feel powerful most of the time. In day-to-day life, I often feel splintered, like parts of my soul have been buried or shut away. It’s hard to access and accurately express them to others. It’s a struggle being a person in society, and it’s not because I’m a mysterious badass. I’m neurodivergent, socially anxious, and incapable of fakery unless I’m pretty much silent. I’m constantly monitoring my facial expressions and body language, trying to appear the way I think I should. When I don’t know how to act, which is most of the time, I paste on a neutral smile and suffocate the discomfort until it’s time to go home. Sometimes I wonder why I’m always exhausted, and then I remember why.

As a kid, I loved to dance, sing, and perform. I was always putting on shows for anyone who’d give me the time of day. My parents got divorced when I was a couple months old. My household was relatively loving, but distant. I had a mom and a stepdad who were consumed by their work as physicians. As a result, I spent most of my time alone in my room, obsessively listening to basically every ’90s album ever made. Songs became containers for my vivid daydreams, each artist guiding me into their world until it became my own. They were me, and I was them. It felt like the songs were pieces of a cosmic puzzle—if I could fit them all together, I’d understand the meaning of existence.

I spent most of my childhood in a small suburb of San Antonio. Back then, it had a rural charm, though it’s since been swallowed by development. I remember the fusion of tejano and country roots music, the rolling hills, cedar and mesquite trees, and wildflowers—all of it laced with a kind of dangerous beauty: cacti, scorpions, fire ants, rattlesnakes. The juxtaposition of muted pastels and sharp edges still informs who I am today.

When I was 13 we moved to Springfield, Missouri, which was quite the culture shock. It’s not as if the place doesn’t have some redeeming qualities, but at the time it felt like the whitest, emptiest, strip-mall town on the planet. Not long after we landed there, I started getting badly bullied by my peers. At the time, I was expressive, bold, and sensitive—all things that made me an easy target. The disdainful looks, the whispers, the eye rolls—each felt like a blow to the heart. Ashamed, I started to stuff down who I truly was. I didn’t have the language to adequately express what I was going through to my parents, and when I tried, I felt dismissed. It wasn’t a big deal. It was life.

That’s when I started drinking and doing drugs. I couldn’t be myself sober without feeling ostracized, but hiding was unbearable too. Partying with other people who felt the same offered a type of safety—a place where my buried self could emerge. I didn’t have to hold it all together anymore.

I was always writing songs and singing, but I never committed to an instrument. I took piano lessons, had a drum set, dabbled with my brother’s guitar. But being mostly alone in my youth combined with my ADHD made it hard to stick with anything.

Finally, I wrote and recorded a song on GarageBand when I was 18. When I went to visit my dad in Minnesota, I played the song for him. His reaction stung when he said “Sweetheart, this isn’t you.” When I insisted that it was, he said “Honey, I know what you sound like, and this isn’t you.”

That moment crystallized the lifelong ache I knew so well: the feeling of being misunderstood.

I don’t know what lie I could have told in the past that would make him believe I’d fake something like that. His response made me feel like I couldn’t possibly be good enough to create something beautiful. It was a strange, horrible feeling to be known so little by my own father—to be mistaken for someone who would fabricate a song, and for him to claim he knew my own voice better than I did. When clearly, he didn’t.

I have a good relationship with my dad now, but that moment still permeates my life in a lot of ways. Even now, when people are surprised by my capabilities as a songwriter, it pisses me off. I know they mean well. It might even just be that they’re impressed. But it brings back memories of being unseen all my life—of all the people who were sure they knew me, but never really did.

Playing music with my band—and being around other musicians—is the only time I feel fully witnessed. Committing to music was a turning point; it was only then that some of my toxic patterns and unhealthy habits began to fall away. It was a long road to get there, but worth it. In a way, I have feeling misunderstood to thank for my art. While my songs are inspired by nature and the depth of human relationships, they’re also fueled by a deep desire to show who I truly am.

Like those daydreams I had as a child, I imagine the listener merging with that truth—I am them, and they are me. Real connection is more intricate and nuanced than fleeting social interactions. We all want to be seen. Love can only flourish when we remember this about each other.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I was always a writer, but didn’t get into songwriting until my late teens/ early 20’s. I started with the piano because it was the instrument I was around the most growing up. At the age of 27, I taught myself to play guitar, which is now my main instrument. I was always musical, but more interested in dating a musician than actually being one. I just didn’t feel capable. It was as if I was trying to have the experience of being a musician by living vicariously through friends and boyfriends. It wasn’t until I went through a particularly painful heartbreak/ break up in my late 20’s that I started to get serious about music. I tried a ton of different jobs before then, but my performance at those was always mediocre, at best. I felt like such a failure, especially coming from a family full of extremely high achievers.

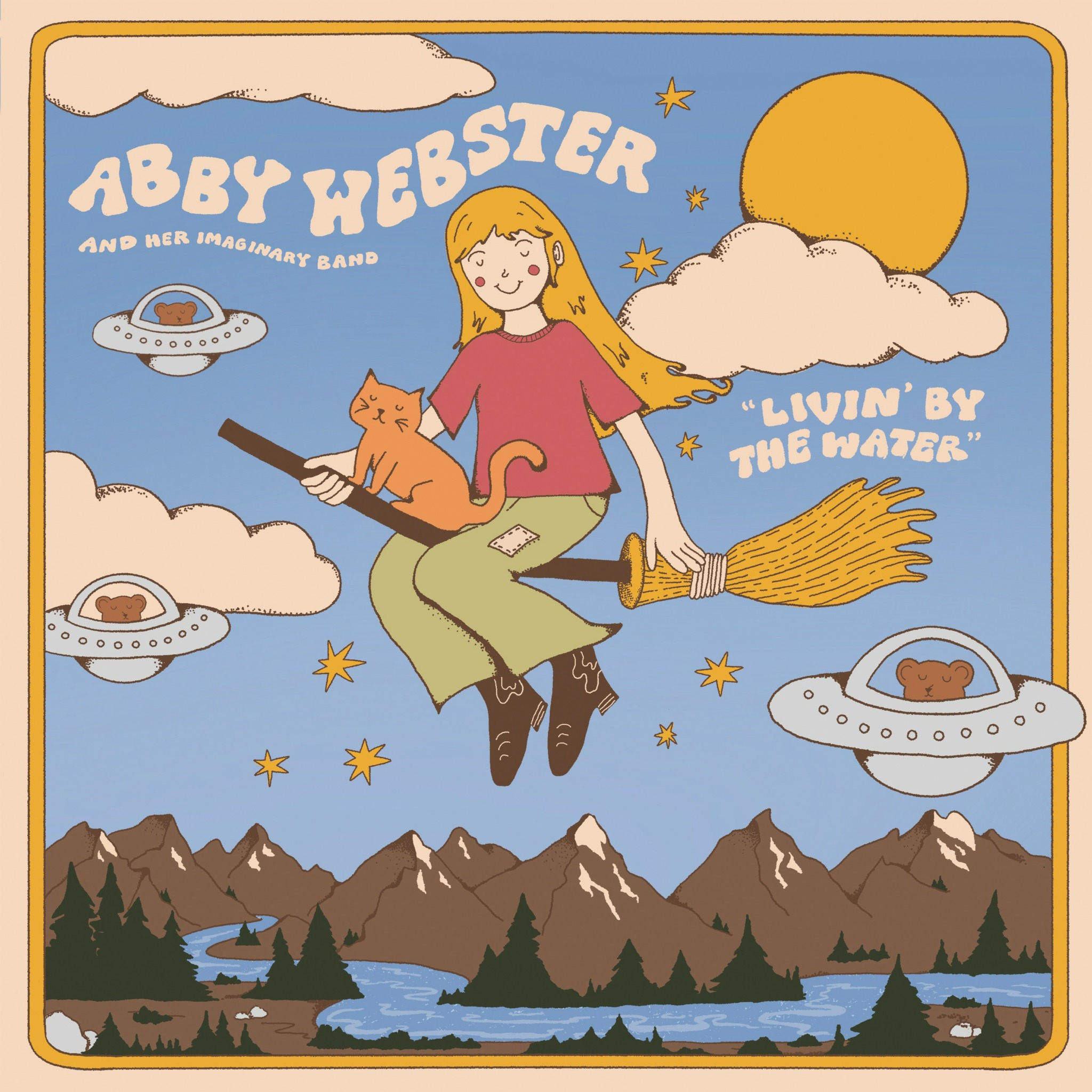

Like my previous response suggests, I think my music allows others to feel seen in some way. When writing is specific and honest, it has that effect on people. The thing I’m most proud of at this time in my life is my band and all the people who surround us. We are all chosen family and so lucky to get to grow and experience the beauty of music together. My first album, “Livin’ by the Water,” was an enormous accomplishment for me as someone who struggled to finish literally everything my entire life. I couldn’t have done it without all the people who believed in me and helped me make it happen.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I’m constantly unlearning beliefs about myself and others, that never stops for me. I think that’s where my art flourishes. Our judgements and beliefs shape our reality. Every song is, in some way, a process of unlearning and transmuting.

Some examples of limiting beliefs I’ve had to unlearn are: I have to be drunk to perform. My music isn’t worthy of money. I’ll never be good at guitar. I’m too old to be on this career path. The list goes on.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

It’s impossible to choose the job of “singer-songwriter” or “musician” without a tremendous amount of resilience.

One time I was at a bar in Colorado Springs and I started talking to the man sitting next to me. He asked me what I did and I told him. He essentially said that it was impossible to make a living as a musician, that I wasn’t going to be “the next Katy Perry” (his exact words), and that I should be realistic and find something that actually offers a service to others. Shocking as this interaction may seem, it’s actually quite typical. It took me a long time to just “own it” when I tell people what I do, because most people don’t view it as a real job and dismiss it as “a hobby.”

Most professional musicians do it because there is something they can’t explain propelling them forward. It feels like there’s absolutely nothing else they can wholeheartedly do except music. It’s a bonkers career. It leaves you never knowing how much money you’ll make. Your schedule is all over the place, leaving you circadian rhythm a hot mess. You face constant judgement and rejection from all directions. But you just have to keep going, sometimes playing for empty rooms or having people talk over your whole set. It’s truly the most vulnerable profession I can think of and I wouldn’t wish it on my worst enemy. But there’s no other path for me, and I accept that now.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.abbywebster.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abbywebsterrr/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@abbywebsterrr

- Other: https://open.spotify.com/artist/0HhLNo5pI32wCYNKqpXuCD?si=6peZ-3LsSpS4LYAXJQL3yA&nd=1&dlsi=c3496f08b25c4187

Image Credits

Grace Mesenko

Gregory Webster

Bo Stephenson

Gillian Wormwood

Bob Wall