We were lucky to catch up with Pioneer Winter recently and have shared our conversation below.

Pioneer, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Are you able to earn a full-time living from your creative work? If so, can you walk us through your journey and how you made it happen?

Yes, but it took a minute.

Fresh out of grad school I juggled three gigs: choreographing anywhere that would have me, adjunct teaching at FIU, and public-health outreach. That mash-up kept the lights on and bought me studio time. Eventually I realized I had to treat Pioneer Winter Collective as its own little world—shows, community workshops, a screendance fest, and my university teaching all feeding each other. Funders loved that ripple effect: the 2022 Creative Capital Award and National Performance Network support cracked open multi-year grants and legitimated the model.

A few checkpoints made the income reliable:

2014: landed an adjunct faculty job that gave me a steady paycheck and I taught up to 8 classes a semester, which allowed me to get health insurance while I kept making art.

2016: turned the Collective into a 501(c)(3), which opened the grant opportunities and let me expand the circle of collaborators I was working with.

2017–present: secured partnerships and national residencies that pay collaborators and cover my research time.

Ongoing – keep diversifying: touring fees, teaching residencies, film licensing, plus a new archiving service that attracts tech-savvy funders.

Could I have sped things up? Who knows. Faster is not always better; resilience often grows in the pauses.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I’m Pioneer Winter, a Miami-raised choreographer who believes dance belongs everywhere and to everyone. I run Pioneer Winter Collective, an intergenerational, physically integrated dance-theater company that turns streets, museums, gardens, and film screens into stages. My path began on my mom’s tap-dancing feet, detoured through public-health work fighting HIV stigma, and landed back in the studio when I realized movement could ask the same social questions my data sets did—only louder.

What we make and why it matters:

Live performance: roaming site-specific works like Grass Stains; mainstage pieces such as Apollo, which premiered to sold-out audiences with an intergenerational ensemble bridging nearly four decades of queer dance lineage on one stage; and the upcoming In the Belly of the Bird/Godmother, a meditation on grief, memory, and a lost parrot voiced through dancers in their 60s.

Workshops and residencies: for recovery groups, universities, and anyone willing to move, using dance to build community, agency, and joy.

Why we do it:

Traditional dance often sidelines older bodies, disabled dancers, and queer narratives. We bring them front-and-center, proving excellence has many forms. Presenters call when they want community engagement that feels real; audiences show up when they crave art that makes them feel seen.

What sets us apart:

Our mission is to expand the definition of dance and ensure all bodies survive, thrive, and are witnessed. Every project is an ecosystem; performance, education, and social practice feed one another, keeping collaborators working year-round and inviting audiences into the creative process. Funders like Creative Capital, the Mellon Foundation, and the National Performance Network back this model because it pairs artistic rigor with social impact.

How the work moves:

I look for “the right movement out of necessity”—the clearest gesture to express the moment, stripped of excess yet still flowing as dance. Less ornament, more truth-in-motion.

Proud moments:

Miami-Dade County proclaimed April 25 “Pioneer Winter Collective Day.”

Apollo premiered to sold out shows, starring an intergenerational quartet of queer dancers.

Over 3,000 students have passed through my FIU classes.

What I want you to know:

Show up to a PWC event ready to feel both invited and challenged. Our pieces ask big questions about power, consent, and care, yet they meet you where you are—whether you’re in a theater seat, a lawn chair, or scrolling on your phone. If we’re doing our job, you’ll leave believing dance has room for your story too.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

A healthy arts ecosystem works like a well-rehearsed ensemble: every funding source is a different dancer contributing rhythm, lift, and balance. Public dollars often lead the phrase—they let artists take risks and keep tickets accessible—but they’re also the first to exit when political winds change. Pioneer Winter Collective felt that abrupt shift this year when both the State of Florida and the National Endowment for the Arts pulled grants that had powered our core programming. County grants and private foundations have stepped in generously, yet their support is usually tied to specific projects and short runs; it rarely covers the steady, everyday work—artist pay, rehearsal space, community workshops—that makes the spotlight moments possible.

To keep the choreography alive, we need a fuller cast. Corporations can underwrite touring or technology, and policymakers can restore (or at least safeguard) public arts budgets. But the most agile partner is often the individual “angel” donor—people with disposable income who believe in the larger social good of the arts and are willing to step up when it matters most. Their unrestricted gifts let us pivot in real time: offering pay-what-you-can classes, providing transportation stipends so dancers who rely on public transit can attend rehearsals, or bringing a performance to a neighborhood that has never seen contemporary dance.

Supporting work like ours is not charity; it’s an investment in civic vitality. When audiences see disabled, queer, and older bodies moving powerfully onstage, they carry that expanded sense of possibility back into their own lives and communities. If we want cities that innovate rather than stagnate, we need artists who can afford to experiment—and the layered support structure that lets the whole ensemble keep dancing.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

The best part, hands down, is witnessing that flash of recognition…when someone in the audience suddenly sees themselves in a body or a story they never expected would mirror their own. In that instant all the late-night rehearsals, grant paperwork, and bruised knees line up and make sense. I love making new movement, but the deeper reward is watching a room shift: a teen who thought dance wasn’t “for them” starts swaying in their seat, or an elder performer realizes their decades of living are an artistic superpower, not a limitation. Those moments remind me that choreography isn’t just steps; it’s permission. Every time a piece cracks open someone’s idea of who can dance (or what dance can be) I feel like the work has done more than entertain; it has moved the edges of possibility a little wider for all of us.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.pioneerwinter.com

- Instagram: @ThePioneerWinter

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pioneerwintercollective

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/55344059/admin/dashboard/

- Twitter: @PioneerWinter

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SnkD8TZiPeE

Image Credits

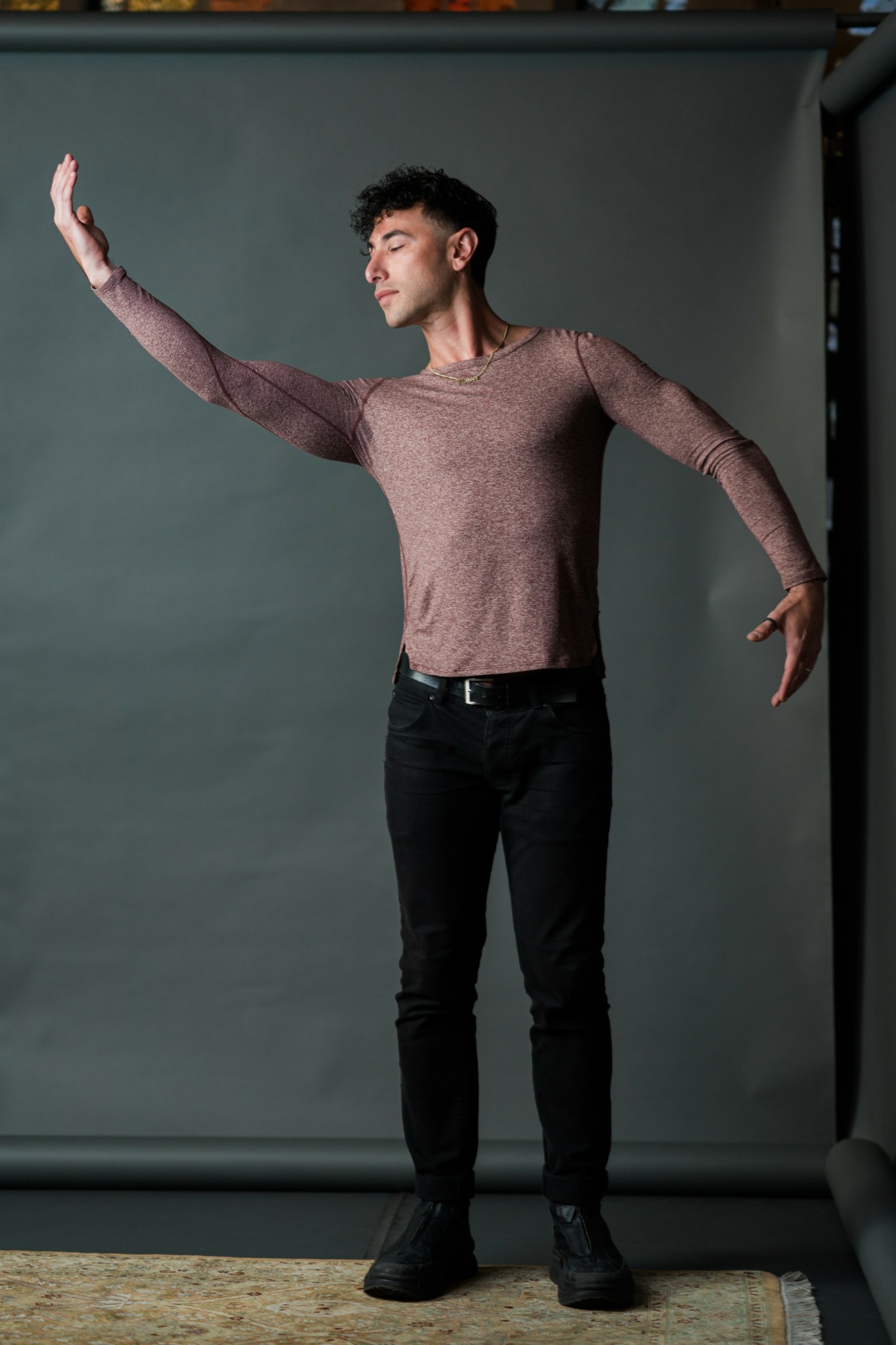

image 1: PWC in “Birds of Paradise” photographed by Passion Ward (2023)

image 2: PWC in “Reprise” photographed by Mitchell Zachs (2019)

image 3: PWC in “Birds of Paradise” photographed by Simon Soong (2024)

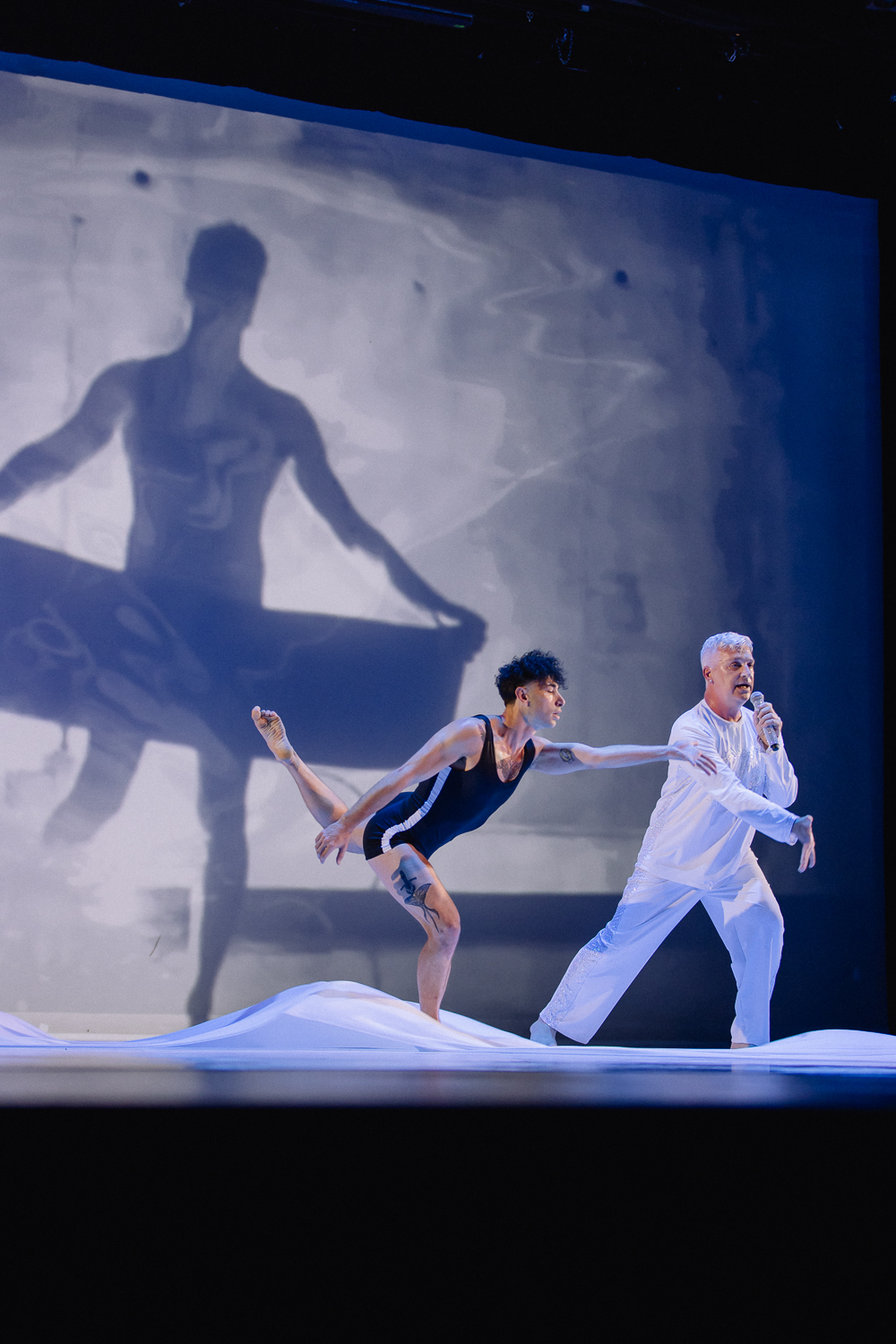

image 4: PWC in “Reprise” photographed by Mitchell Zachs (2018)

image 5: PWC in “Gimp Gait” photographed by Tabatha Mudra (2016)

image 6: PWC in “Forced Entry and Other Love Stories” photographed by Mitchell Zachs (2017)

image 7: PWC after premiere of “Apollo” with a Proclamation from Miami-Dade County mayor, photographed by Passion Ward (2025)

image 8: PWC in “Apollo” photographed by Passion Ward (2025)