Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Sepehr Davallou. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Sepehr, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

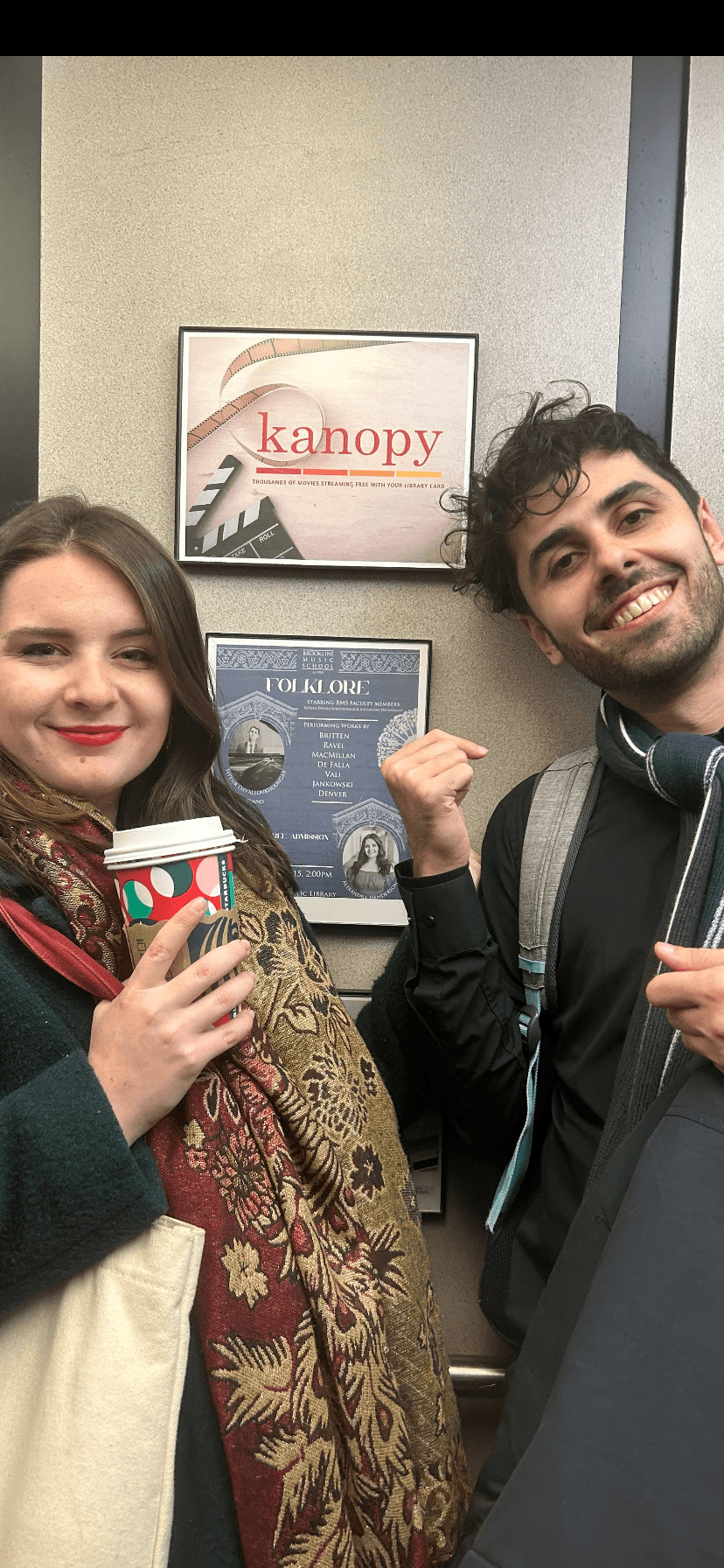

I recently presented and curated an Artsong recital alongside my fantastic soprano duo, Alexandra Henderson, at the Zimmerli Art Museum in New Jersey at the invitation of the Federation of the Artsong. The recital titled “Folklore” was the second iteration of this program that we had envisioned and worked on for many months and it sought to bridge the gap between folk music and the standard repertoire of Artsong usually heard in recitals. It explored Spanish, Greek, French, American, and Persian musical settings of folk music by Ravel, De Falla, Copland, and Reza Vali. We were able to present this program back in December, in Boston’s Brookline Public Library and the process of shaping it for two recitals over five months was very meaningful as it enabled us to study these works very closely. Since the music is based on folk traditions, it has a close relationship to the cultures it comes from and this makes the works less “classical” or “academic” in style and instead requires close study of the originating culture and the languages they are sung in. I discovered how some understanding of Flamenco dance styles was necessary to be able to translate the written notation of De Falla into living music on the piano. Without such understanding, the notes on the page become bland and won’t express the intention correctly. The specific piano technique and touch should be very distinct in each of this repertoire and the correct approach is achieved only after that kind of in-depth study. It was immensely meaningful to have such a palette of cultures and soundworlds packaged cohesively for our audiences. What was profoundly important is that we got to engage with our audiences in both concerts, and while walking them through the journey of the songs and their creation and what they meant to us, we also got to ask them how they felt about going on such a worldly musical journey with us, and to our gratitude, we found that they found the recitals to be very engaging, enjoyable and impactful. I believe the most meaningful experience for a musician is to be able to hear from their audience that they connected with their performance in a genuine way. This is what all of us strive for.

Sepehr, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I am a classical pianist, specializing in a very specific and niche field of this industry: Vocal music and opera. This means I get to work with singers in many settings and on many projects. I play for and/or conduct operas. In this kind of process, I might coach the singers and prepare them for their roles, play as a repetiteur during rehearsals and staging, and play any keyboard instrument that is in the orchestration in the pit such as harpsichord, celesta, and organ. Believe it or not, during Miami Music Festival’s production of Midsummer Night’s Dream by Britten, I have also covered the flute in the pit on a keyboard with a flute effect due to an emergency absence of a flutist! During my coachings, I fix problems such as diction, musicality and musical detail, and go into discussions about interpretation, style, and storytelling.

I also work with singers on Art songs and curating recitals. I work with choruses and lead sectionals while preparing the choruses for performance. These various settings put me in close contact with many genres of music, and many languages which I have had to study, know and perfect over the course of many years.

I got into this corner of classical music while I was working on my Master’s degrees and I played for a lot of singers’ recitals and started playing for operas. When I started working with musicians in the opera world I knew that’s where I am headed next, and that’s where I have been since. For many years, I have learned thousands of songs and arias and familiarized myself with the vast and infinite repertoire of vocal music to be able to succeed as a vocal pianist and coach.

On top of all this, I also am a piano faculty at two well-known music schools in the Boston area, where I teach as many as thirty students a week. During my lessons and coachings with piano students, I have made many discoveries about piano technique, pedagogy, and the immensely intricate role our brain plays while learning music and an instrument.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

For me, the best and most rewarding part of being an artist is the variety and sheer number of projects I get to work on. In a span of a week, I go from playing jazz music to leading or teaching a chorus. Next day I am in opera rehearsals all day, playing as repetiteur in a Baroque opera and playing the harpsichord in the orchestra pit. The day after I am studying poetry and working on some artsong. I might have to play for workshops, masterclasses, recitals and competitions, or coach a singer preparing to sing a role in an opera. There is no boredom in this line of work, and every day is a different story, a different challenge to tackle and rewarding experiences that come from it. I love this, and knowing my personality, I couldn’t imagine myself doing anything else.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

Seeking perfection in the wrong place is one thing that I have had to relearn and rewire my brain. As artists, most of us grow with some degree of perfectionism. I believe that the perfectionist drive is what makes one want to become an artist in the first place. However, where and when you seek it is extremely important. As a classical musician and pianist, it was important for me to learn that the most unrelenting perfect standards, I should impose on myself during practice time. When and after doing so one should allow the performance to happen organically and “allow” the practiced material to come out freely. Usually, our brain has very relaxed standards in the practice room; If a passage doesn’t work 5 times but does the 6th time, the brain says that’s fine, see I got it the 6th time didn’t I!? If we don’t know the text of a song really well, the brain says Eh it’s fine at least I somewhat know the piano part. But then comes the performance time and the brain wants to scramble and impose the highest of standards on ourselves “during” the performance. This needs to be unlearned and then reversed.

I have had to -and still keep reminding myself- relearn this double standard in the opposite way. The highest and strictest of standards in the practice room, and lowering them during the act of performance so the music could come out freely and we can share the music with our audiences.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.sepehrdavallou.com