We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Don Sawyer a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Don, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

I’ve never been risk averse. From protesting the Vietnam War at the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention (and being arrested and jailed) to taking a teaching job in a small outport community in rural Newfoundland sight unseen to travelling and working in West Africa. taking risks has been part of my character — and has enriched my life and my writing. One of my guiding tenets is summed up by Canadian cultural anthropologist Wade Davis: “There is a difference between discomfort and danger.”

I grew up in Michigan and came to Canada in the 1960s to attend the University of British Columbia, where I more or less flunked out of my PhD program in Modern Chinese History. This turned out to be a blessing as it opened up a world of opportunity and experiences I had never contemplated, starting with a two-year stent (1970-72) in a remote outport community in rural Newfoundland. (In those days Newfoundland faced a grave shortage of teachers and were so desperate they hired me, never having taken an education course, to teach in the high school and my wife in the elementary school.) These were two magical years as I learned from my students how to teach (highly recommended) and the town about community, self-sufficiency and resourcefulness.

And I got my first book out of it: Tomorrow Is School and I am Sick to the Heart Thinking about It. (Described as “the moving tale of two novice teachers who find themselves in a place like no other, facing challenges many teachers can only imagine,” the title was taken from a note left by one of our students, who took to coming up to visit many evenings.) It turned out I was also a pretty creative teacher, spinning ideas from the raw materials of the physical and social environment where I taught and seeing how the kids responded.

During that time I wrote letters (yeah, real hand-written letters) to friends describing our adventures. When we left to return to grad school, a poet friend convinced me that all those letters I had sent him could be the basis of a book. Really? A book? But I knew I had a story I wanted to tell, a story that needed to be told to honour the students who had taught me how to teach. It might be worth a try.

By that time my wife and I had finished our university programs and had taught for two years in a small indigenous community in the Fraser Canyon of British Columbia. This too was a transformative experience, but I left to be with my father, who was dying of cancer. During this period I had most of the days to myself. The experiences in Newfoundland were still fresh and strong, demanding to be written and shared. So I wrote a book. And it became a Canadian best-seller. And I was amazed. And then it was used in teacher training programs, and I realized my creativity could not only entertain, but also have an impact and contribute to change for the better. The rest of my career was shaped by those experiences in Newfoundland – I became an educator and an author.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

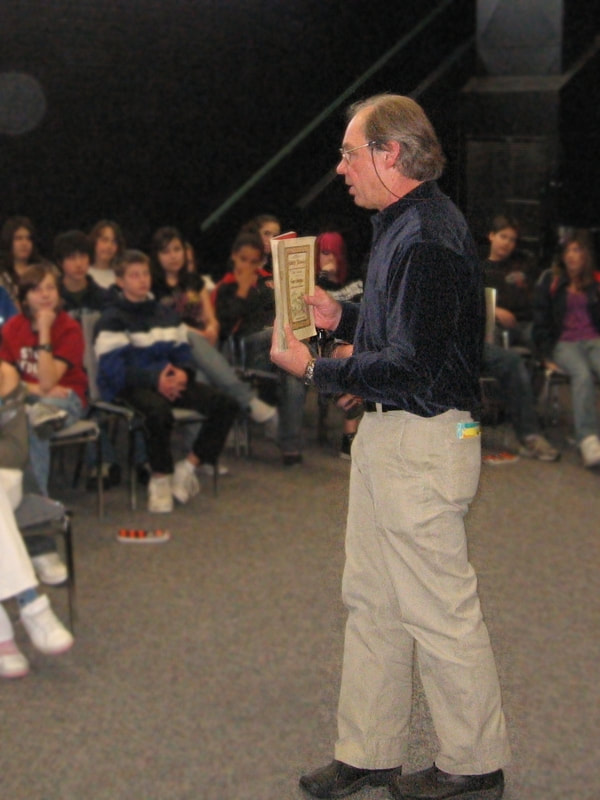

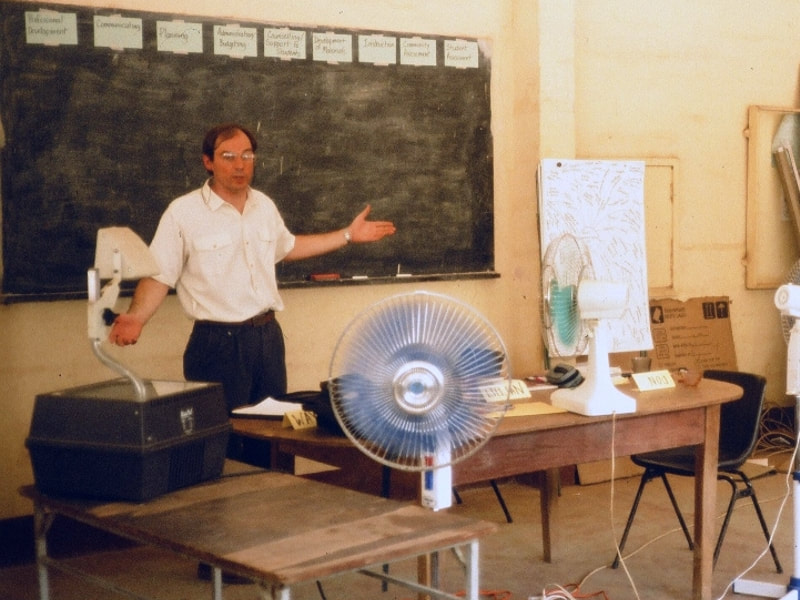

An educator and writer, I grew up in Michigan and came to Canada in the 1960s, where, as mentioned, I more or less flunked out of my PhD program at the University of British Columbia. What luck. Partly out of sheer desperation, I turned to opportunities I had never considered. And what great experiences they have provided. From teaching in a small Newfoundland outport to training community workers in West Africa to teaching adults on a First Nations reserve in British Columbia to designing a climate change action course for Jamaican youth, I have worked with youth and adults from many cultural backgrounds and in a variety of locales.

Inevitably, these experiences have made their way into my writing. I have authored over 12 books, including two Canadian bestsellers: the YA novel Where the Rivers Meet (Pemmican) and the adult non-fiction Tomorrow Is School and I Am Sick to the Heart Thinking about It (Douglas and McIntyre). The first book in my Miss Flint series for children, The Meanest Teacher in the World (Thistledown), was translated into German by Carlsen and Ravensburger. My articles and op-eds have appeared in many journals and most of Canada’s major dailies

Before moving to Ontario, I lived and worked in Salmon Arm, BC for more than thirty years. There I taught adult education, served as the Chair of the Okanagan University College (OUC) Adult Basic Education Department, and Director Curriculum Director for the Native Adult Education Resource Centre. My published work has ranged from children’s chapter books to adult non-fiction. I have written two successful YA novels and a series of novellas for adults with limited reading skills.

I have also written hundreds of pages of curriculum. Writing is a remarkably transferable skill, and as writers we can apply our skills and knowledge to an astonishing array of situations. In my case I worked with an extraordinary team of African and Canadian educators and community development workers in both Ghana and The Gambia to create one of the most effective training programs for grassroots community in Africa. I edited and wrote a guide for teachers of English to Canadian indigenous adults. In Jamaica I was the primary writer on an innovative curriculum for the training of youth as climate change agents. I have written teacher’s guides for use with a dozen books, including five of my own.

Writing has been my avocation and vocation. My published writing has been an essential outlet for my creativity and a way of sharing stories that matter to me. My professional writing has helped me earn an income while impacting teaching and training from British Columbia to West Africa. A writer friend of mine says this is what he wants engraved on his tombstone: “Well, at least he got a book out of it.” I am much the same way – I write what I’m passionate about and that has arisen from my experiences

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

When my first book, Tomorrow Is School, was published in 1979, I was delighted to see the book finally come out and looking forward to the rapturous praise it would certainly receive. Jan and I were in a hotel in Vancouver that delivered the Vancouver Sun to our door each morning. This particular morning I sat down in an upholstered chair with a cup of coffee and idly leafed through the paper – until I saw the cover of my book in the book reviews. (Yes, in those days paper actually had sections dedicated to book reviews.) My heart rate soared – the book had just come out and this was its first published review. How exciting! And then as I scanned the headline, which read something like “Boring Teacher Memoir Sucks Big Time” (not those words exactly, but you get the idea), my heart dropped into the pit of my stomach like a stone.

As I read the review, I felt physically ill. I was completely unprepared. It had never occurred to me that somebody – and especially a reviewer for a major paper – might not like the book and then proceed to detail their loathing very publicly and in great detail.

After I had recovered enough to get my heart under control (and manage not to cry), I called my publisher. He had seen the review and knew I was shattered. He listened to me for a few moments and then said a couple of things that have stayed with me ever since.

“I know how upsetting this is,” Scotty said. “Having a book published is about as close to having a baby as a man can come. There is a long gestation, and then you gently nurture it along for another year of two, and then it’s done. It tottles out the door out into the world and takes on a life of its own. You love it dearly, but you cannot protect it from mean comments or bullies.”

But what about the review? Was there more to come? Was everybody going to hate the book?

“Listen,” my publisher said, “let me give you some advice. Don’t pay any attention to reviews. If possible, don’t even read them, including the good ones. Because if you take the good ones seriously, then you have to do the same with the bad ones. Ignore them all.”

I am happy to report that the book went on to become a Canadian best-seller and was used widely in teacher training programs across Canada. And I never had another negative review. But that experience and Scott’s words toughened me up so I could work in an industry where rejection and criticism are simply part of the routine.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

Passion. Not so much passion for writing itself – though that helps – but passion for the characters I am portraying or the story I am telling. Most of my writing comes from an issue or experience I feel strongly about. My determination to share my outrage, joy, admiration, sense of social injustice – these are what power my writing and demand that it be done well.

After teaching in a predominantly Native high school in BC, I took away a slow-burning anger at the crushing impacts of colonialism I saw everywhere – in the school and in the community – on the young Native kids I was teaching. I wanted to show how the mismatch between the home and community of the students and the rigid, irrelevant, hierarchical structure of the school devastated kids already struggling with identity and whose families were often shattered by violence and substance abuse.

And so I wrote my first YA novel Where the Rivers Meet based on my experiences, and it was propelled by that anger. In the book, the ability to fight back came from the students’ traditional teachings and elders. The central character led a strike at the school. They were mad as hell and they didn’t take it anymore.

The story fairly blazed with rage, because that is what fueled me as I wrote the book. When I submitted the manuscript to a publisher (who had published a previous book of mine with great success), the editor wrote back and said the young woman main character was “too sophisticated in her analysis” and the actions of the students “not believable.”

The publisher didn’t get it. But my passion to explore the injustices I experienced and their impacts on young Native adults wouldn’t let me give up. I submitted it to a small First-Nations-owned press, and they took it immediately.

The book was an immediate success, not just with critics, but more importantly with Native students across Canada. It was reprinted six time in 10 years. Students using the book in their classroom or reading it on their own sent me letters about how they related to the story. (One reader commented “This is the only book I’ve ever started and actually finished.”) That character who was too angry, too sophisticated? Apparently not. “A lot of the book reminded me of when I was going to school, the racism. But the only thing different from me and Nancy is that she did something and I quit. But now I’m back to school and this time I’m going to do it.”

That passion that drove me to write the book also permeated the characters and charged the setting. That’s what made it work.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.donsawyer.org

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61558529432508sawyer

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/login/

- Other: https://www.northerned.com/

Image Credits

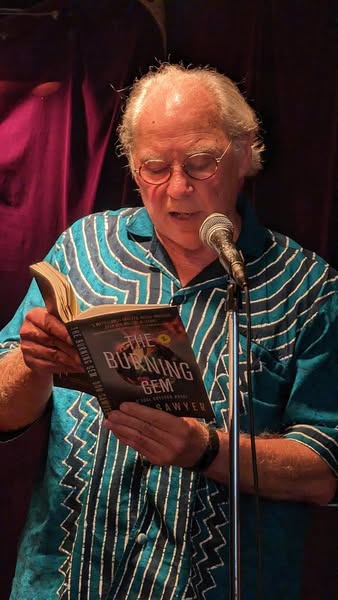

Terence Fowler (reading at Mic)

Ran Elfassy (shooting it raw)