We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Weiyu Xu a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Weiyu, thanks for joining us today. We’d love to hear the story of how you went from this being just an idea to making it into something real.

Where It All Started

When I was a child, I moved around Shanghai with my mother, often finding ourselves in empty, unfinished apartments. The city’s real estate market was booming, and investors were rapidly reshaping its skyline. I remember standing in those raw, unpolished spaces with my mother, imagining how they could become a home. We would brainstorm, sketch, and visualize where walls should go, how light would fill the rooms, and what kind of atmosphere we wanted to create. It was in those moments that I discovered the joy of shaping space. From adjusting a single wall to envisioning an entire apartment layout, my influence on my surroundings grew. And with that, so did my ambitions. I didn’t just want to design homes—I wanted to design at a larger scale. I wanted to become an architect.

From Idea to Execution

My journey took me through formal education—first at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, then at Columbia University. This phase was all about research and exploration. I studied case precedents, analyzed site contexts, and experimented with materials. I was particularly drawn to architecture’s ability to shape emotions, using light, reflection, and organic geometries.

This fascination deepened when I stepped into La Sagrada Familia. The cascading light filtering through the stone columns triggered a powerful nostalgia—the same warmth I once felt beneath the camphor tree in my grandparents’ yard. That moment solidified my belief that architecture is more than just structure; it is a vessel for memory, a medium for translating emotions into space.

Beyond academia, traveling became an equally valuable teacher. Walking through different cities, I observed how built environments shaped human experiences. Every place told a story, and I wanted to learn how to craft my own.

Bridging Concept and Reality

Execution was the most critical phase. The biggest shift came when I started working and realized that in school, I had mostly interacted with fellow designers and architects—but rarely with clients. Design in the professional world was not just about aesthetics or theory; it was about understanding business, investment, and user needs. I saw this firsthand during my internship at Fosun Tourism, where I worked on the client side of architecture, and later at McKinsey, where I was exposed to the strategic decision-making behind projects. These experiences reshaped my understanding of architecture as a profession.

To move beyond the conceptual phase and into real-world practice, I focused on expanding my network. I reached out to professionals outside my discipline—developers, investors, material scientists—because architecture does not exist in isolation. I needed to understand how decisions were made from multiple perspectives. This shift in mindset helped me bridge the gap between artistic vision and pragmatic execution.

Bringing Ideas to Life

The process of turning ideas into reality was iterative. Translating a vision into a built form meant making decisive material choices, coordinating with fabricators, and responding to unforeseen challenges. The first built prototype was a major milestone. Seeing the concept materialize confirmed that architecture could live beyond sketches and models—it could exist as a tangible experience.

That realization continues to guide me today. I have learned to navigate between conceptual and client-driven design, allowing each to inform the other. Whether experimenting with new ideas or delivering practical solutions, I approach each project with the same question I had as a child standing in an empty space: How can we shape this into something meaningful?

Weiyu, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

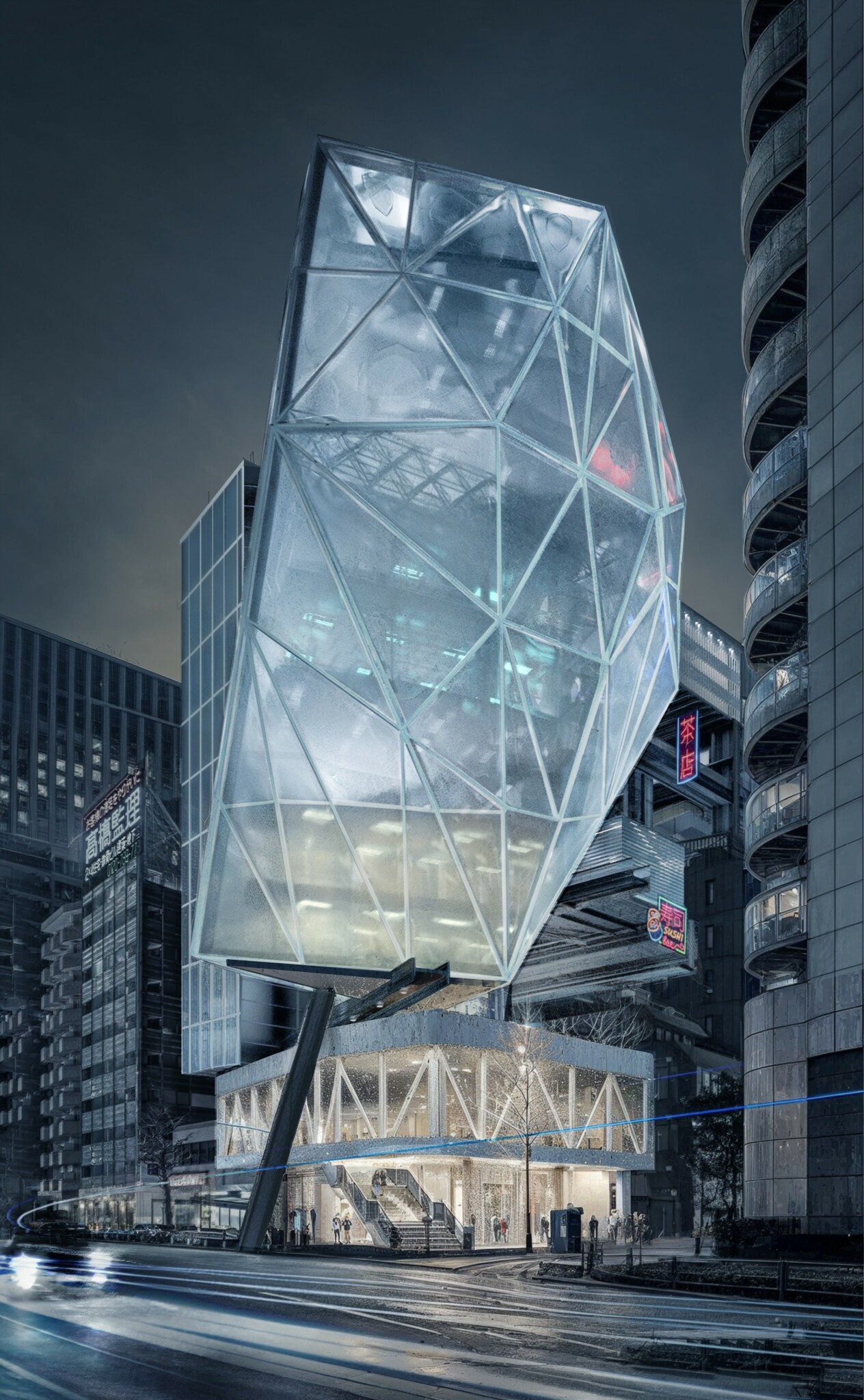

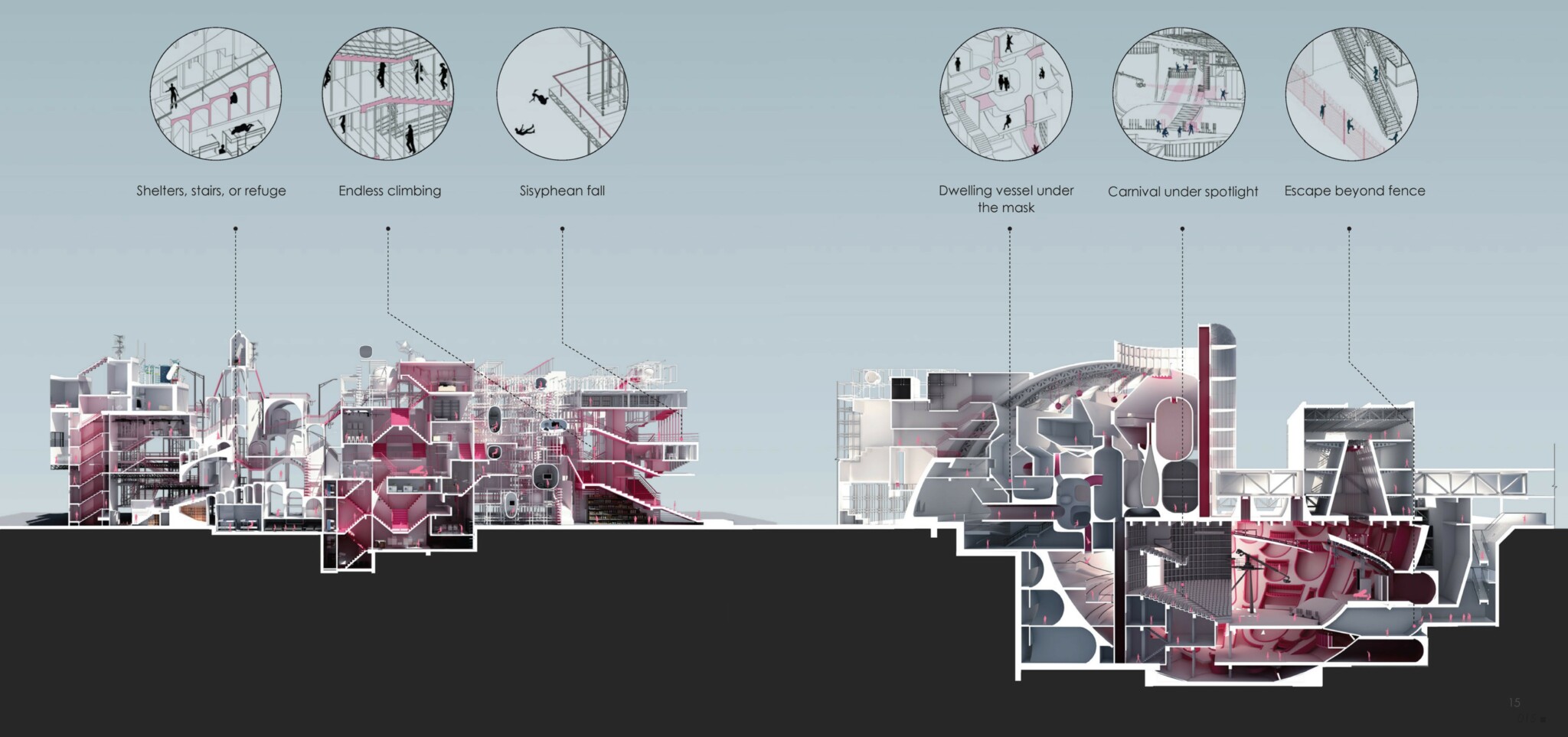

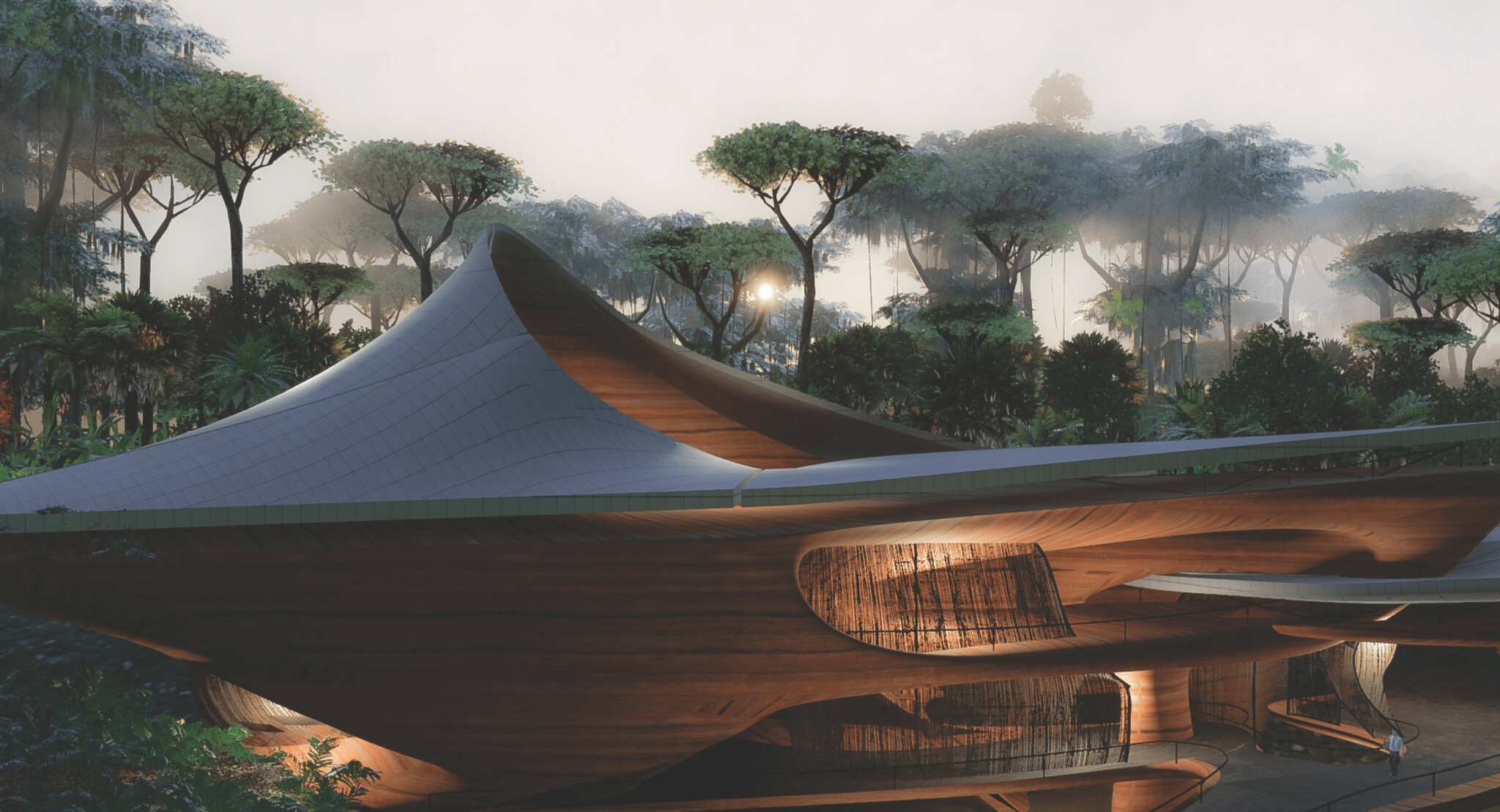

I started SWY in 2024 in NYC, in pursuit of creating spaces that not only serve functional needs but also foster a deeper emotional and sensory connection with the people who experience them. With a belief that architecture has the power to influence human behavior and perception, I set out to explore how design can bridge the gap between artistic expression and real-world application. At SWY, we tackle diverse challenges—ranging from urban regeneration to interior transformations—with the goal of crafting environments that are both innovative and responsive to the complexities of our rapidly evolving cities. Whether through data-driven design or sensory-rich spaces, SWY seeks to shape places that connect, inspire, and endure.

What SWY Creates

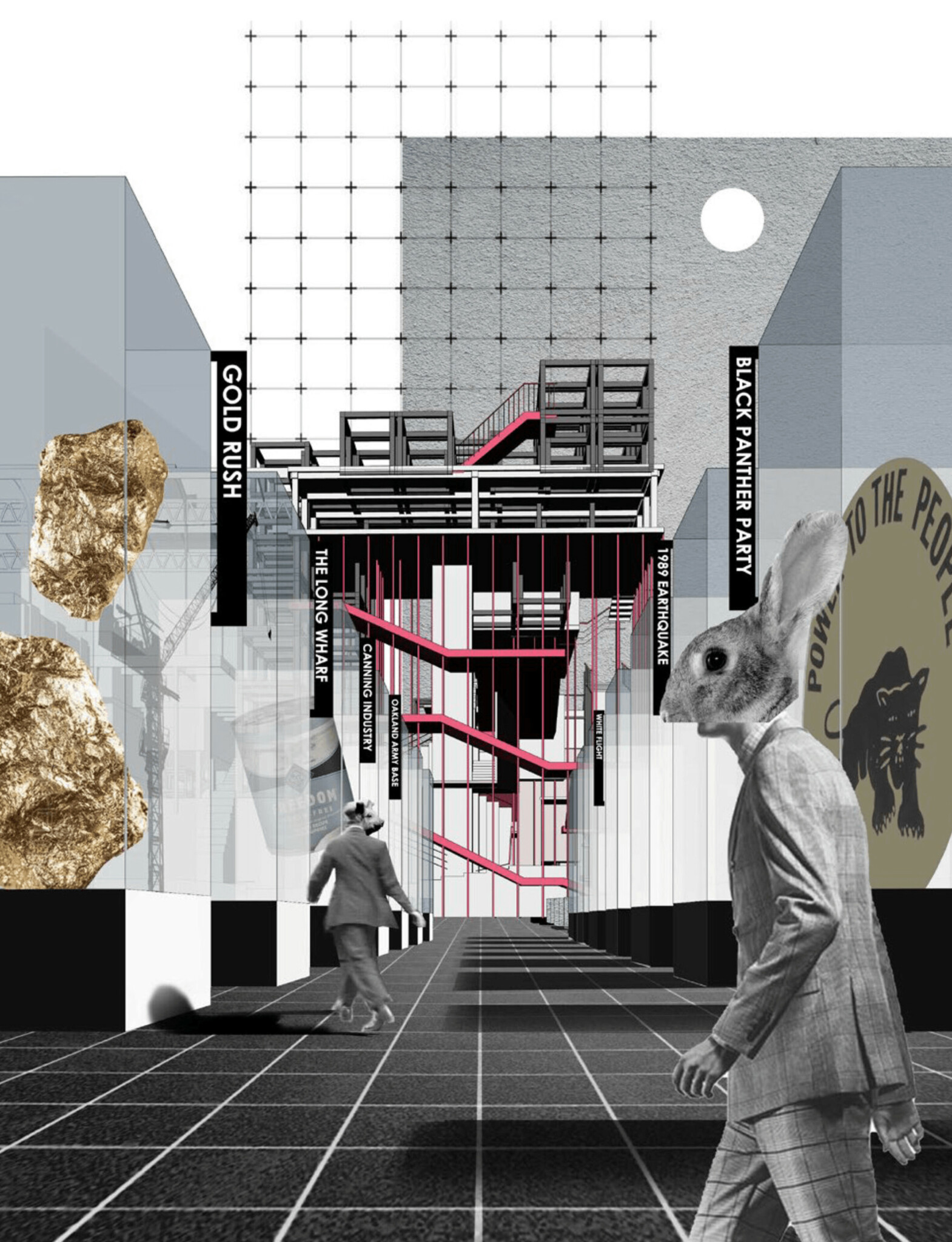

SWY’s portfolio spans urban and architectural design, digital practice, food and service design, and interior architecture. Recent projects include the façade and commercial interior strategy for a supertall mixed-use tower in Shanghai, the master planning of a 1,000,000 sqm theme park in Hainan, and an NYC beauty salon interior that merges parametric design with material tactility.

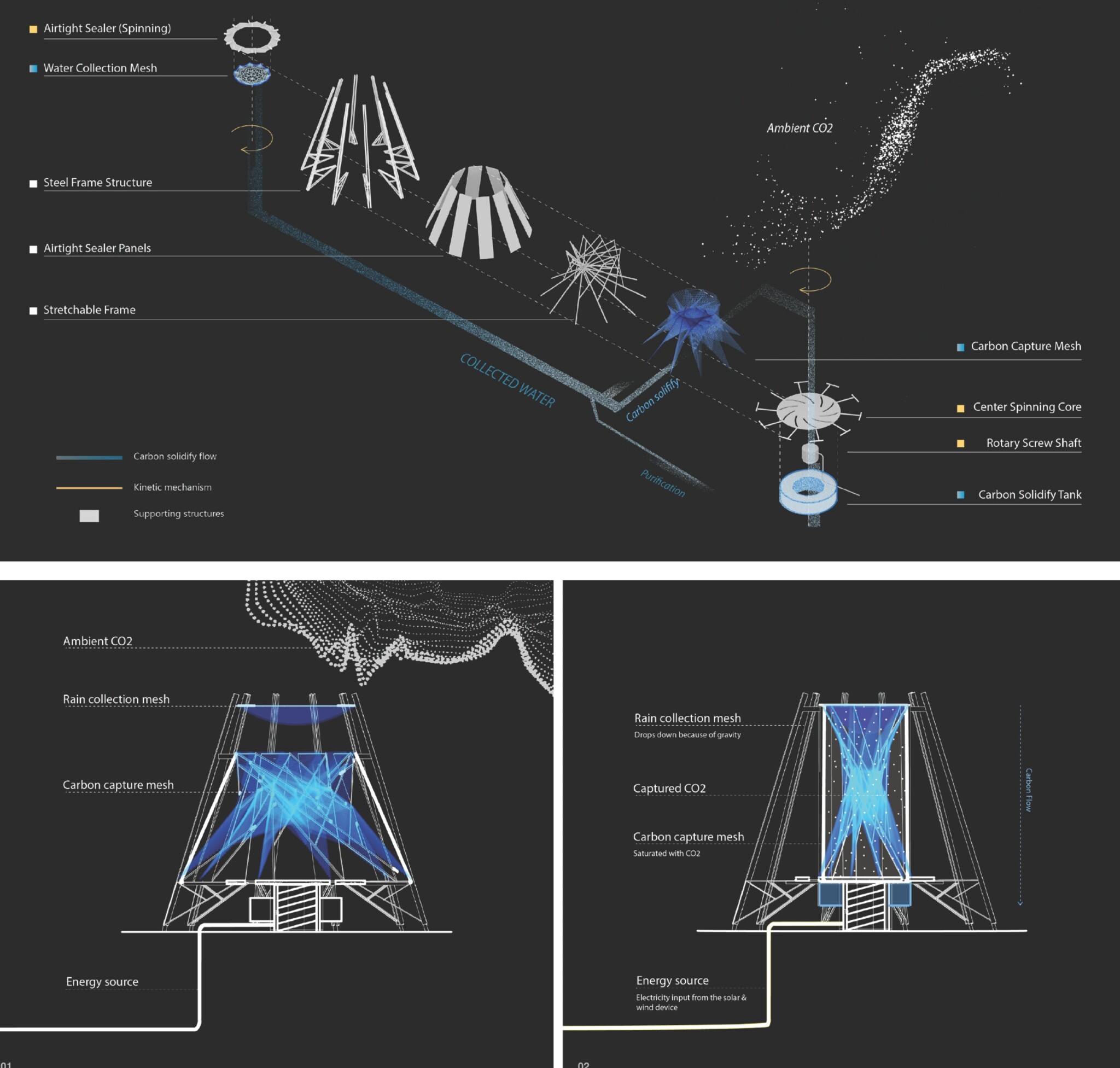

In the digital realm, SWY explores data-driven design strategies such as Aqua Dome, which integrates geospatial data to inform adaptive architectural forms. The studio also reinterprets metabolic architecture in AgriHub, a proposal to transform the Nakagin Capsule Tower into an agricultural hub supporting local food production. This project was awarded the London Design Award (Gold) and NY Architectural Design Awards (Silver).

What Sets SWY Apart

Bridging Conceptual and Client-Oriented Design

SWY balances experimental, research-driven design with real-world execution, ensuring each project is both visionary and functional.

Interdisciplinary Approach

With experience across urban development, digital fabrication, and service design, SWY integrates knowledge from multiple fields to push the boundaries of architectural practice.

Sensory & Phenomenological Design

Spaces are designed not just for utility but for emotion, memory, and human interaction. SWY’s work often incorporates light studies, material experimentation, and computational strategies to craft immersive experiences.

What SWY Stands For

SWY’s design ethos is about not just reclaiming what was lost but shaping what comes next. Through architecture and spatial interventions, the studio seeks to transform built environments into catalysts for social, ecological, and cultural renewal.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

Yes—my creative journey is driven by the pursuit of spatial storytelling and the revival of forgotten connections in urban environments.

We often mourn what is lost to urbanization—the disappearing yards, rivers, and traces of nature. Yet, more than ever before, we are deeply connected to the people around us. The spaces we inhabit, whether virtual or physical, bind us together in ways previously unimaginable. Instead of solely reclaiming what has vanished, I seek to amplify and reframe these new forms of connection through architecture.

As cities expand, cultural layers and human-scale experiences are often erased in favor of efficiency and profit. My mission is to challenge this by designing spaces that restore meaningful relationships—between people and nature, past and present, physical and emotional experiences. I strive to create architecture that evokes memory, engages the senses, and fosters deep interactions.

Have you ever had to pivot?

The biggest turning point in my career happened when I transitioned from academic, conceptual design to client-oriented architectural practice. During my studies, I was immersed in theoretical exploration—pushing boundaries, questioning norms, and designing with an artistic and speculative mindset. However, everything changed when I started working.

My first major realization came through two internships that were outside traditional architecture practice. One was with the design and planning department at Fosun Tourism, a client-side design company, and the other was at McKinsey, purely focused on consultancy. These experiences exposed me to the business side of architecture, where design is deeply intertwined with strategy, economics, and market demands. I saw firsthand how decisions were driven by budgets, branding, and user experience—factors that were often secondary in academic projects.

This shift made me reflect on the contrast between conceptual design and client-oriented practice. In school, architecture was about experimentation—creating speculative visions, testing new materials, and designing without constraints. In the real world, architecture had to serve business objectives, function efficiently, and align with client expectations. At first, I struggled with this duality. I didn’t want to compromise creativity, yet I understood the necessity of pragmatism.

I found balance by embracing both sides. I continued exploring experimental designs, using competitions and personal projects as a space for creativity. But when working on real-world projects, I learned to listen carefully to clients, identify their core needs, and translate their vision into fast, effective design solutions. This ability to navigate between the conceptual and the practical became one of my biggest strengths. It allowed me to bring fresh ideas into client-driven projects while ensuring that innovation remained grounded in reality.

This turning point reshaped my approach to architecture. I no longer see business constraints as limitations but as design challenges. The industry demands both vision and execution, and my role is to bridge that gap—bringing the artistry of conceptual design into the precision of real-world practice.

Contact Info:

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rosalynxu/

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@weiyuxu8242