We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Shannon Arenburg a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Shannon , thanks for joining us today. So, let’s start with a hypothetical – what would you change about the educational system?

I only learned that I wanted to be a pastry chef from the education system. I decided to go to a vocational high school instead of a traditional high school, so I was able to sample fourteen different trades for a week to see where my skills and passion lay. With tradespeople slowly becoming more scarce, vocational schools are more important than ever. The stigma around vocational training is still a hurdle to overcome, so I would absolutely advocate for more interaction with middle school students to let them know that a trade school is an opportunity instead of a punishment.

There is a debate among culinary professionals as to whether formal training is needed to succeed in the industry. Chefs are more likely to hire recent grads from culinary institutions rather than take on training a novice because training someone with little to no experience takes a lot of time that most chefs and restaurant owners don’t have, and the normal mistakes made while learning aren’t within a normal establishment’s budget. Hiring a culinary school graduate means the chef’s time is less burdened by teaching the basics, and there is less of a likelihood of increased waste from mistakes made during the learning process. I personally found professional training to be important to getting my foot in the door for jobs, and those jobs led to valuable mentor opportunities that have shaped who I am as a professional today. However, prestigious culinary schools like CIA and Johnson and Whales are incredibly expensive. Considering the small starting wage that graduates are likely to receive in their first post-college job and the slim margins that food establishments need to operate within, many professionals are having issues with salary. Most starting positions in kitchens aren’t going to cover student loan payments, but from my experience, the American restaurant story of “starting as a dishwasher and working their way up” is not the normal way to become a chef.

I believe that the biggest change that needs to happen here is an increase of support. Either students need to be given more financial support to attend these institutions to get the sought after positions, or foodservice establishments need to be given financial incentives to hire and train novice individuals. When I went into a culinary program for college, I sustained a $24,000 per year scholarship and I was able to structure my course load in a way to graduate in three years instead of four. This privilege gave me the opportunity to interview for jobs that would advance my career without worrying about defaulting on high student loan payments. My alma mater no longer offers the culinary management program, not due to lack of enrollment, but due to these systematic issues.

Since vocational high schools are free, public institutions, encouraging more enrollment is a great start to solving this problem. Since a vocational student will have taken all the basic classes during their time in high school, a four year degree isn’t necessarily needed; admittedly, the majority of the material I had to learn in my first year of college was already covered during my time in the culinary arts shop. One could argue that a vocational high school student that later graduates from an Associate’s program has just as much formal training as a Bachelor’s degree graduate from a traditional high school. If there was a clearer path created for high school vocational credits to count towards secondary education, students could graduate with a Bachelor’s degree in about half the time, with about half the debt. Then, graduates would be in the same position as I was when I graduated: a desirable candidate for the restaurant industry with student loan debt manageable enough to get started in the industry.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I started in the industry when I was about fourteen at a technical high school. I didn’t know what I wanted to do at the time, but baking came naturally to me. I started working for my first small business when I was sixteen and I fell in love with the community. I worked for twelve to fourteen hours a day packaging handmade pasta and selling at farmers markets. I got to know the other small business owners quite well, since the community was tight knit and most vendors would all attend the same markets back then. It was at one of these markets that I met Lydia.

Lydia owned a small candy company specializing in handcrafted marshmallows, caramels, s’mores, and toffee. When she expanded to a brick and mortar location, she added signature candy bars as a kickstarter reward. When I needed an internship that was baking and pastry specific, Lydia took me into the kitchen and I stayed there for a long time, learning everything I could.

I went to Southern New Hampshire University for my Culinary Management bachelors and I studied abroad in Florence, Italy. I believe if you’re going to stand out and be successful in this business, you need to work abroad. It will change the way you think and feel about food. Upon graduation, I landed a job as head baker’s assistant and experienced the opening of a new bakery, then went on to become a pastry cook at a fine dining restaurant in Boston. There are so many avenues to explore in baking and pastry that there are ample opportunities to find your niche without ever getting bored.

Lydia approached me about seven years ago and let me know that she wanted to sell her business. I jumped at the opportunity; I love the confection business, but I also saw it as my chance to eventually expand into my own venture. As of February 7th at 11am, my dream of opening a retail bakery will finally become a reality. I still make all the confections of Sweet Lydia’s, but I have also opened Pizzelle Bakery recipes that I have written and gathered through the years and have been looking forward to sharing.

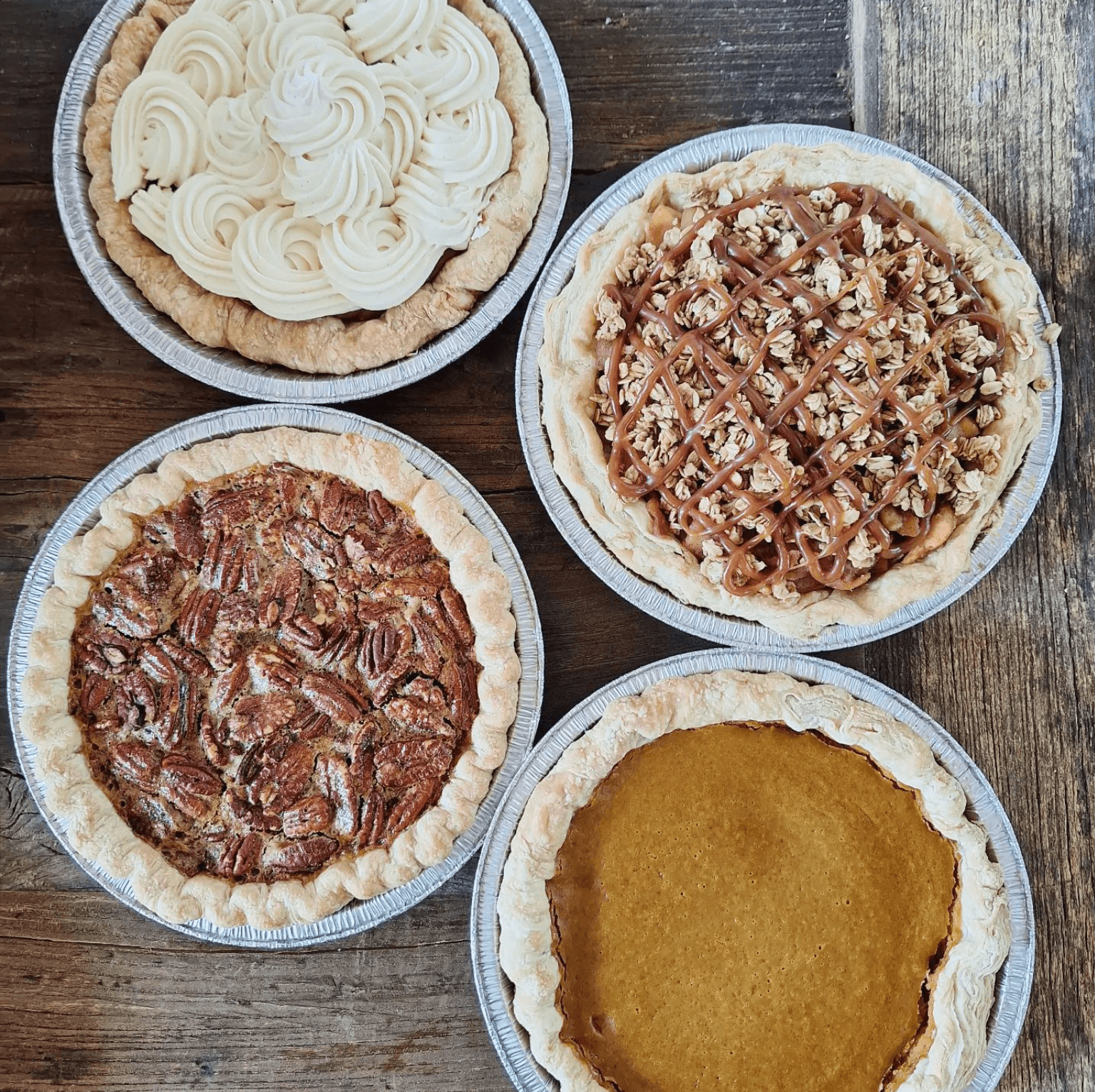

I am so proud of my bakery’s overall vibe upon walking into the space. Upon opening, I reconnected with a friend from my high school culinary program to work with me in the kitchen. Otherwise, my team is made up of passionate individuals that are admittedly a bit green, but make up for it with enthusiasm. We are partnering with a local farm (Brox Farm) to bring CSA shares to downtown Lowell since there isn’t a grocery store easily walkable within the neighborhood. We will be hosting classes and tasting to pass along the knowledge I’ve collected over a long career. I’m hoping that coming these events will inspire and usher in a new generation of bakers. With so many restaurants outsourcing their desserts, this is more relevant than ever. Lastly, I am so proud of our quality. Ingredients are incredibly expensive, and it is only getting worse. Regardless, we are committed to maintaining our standard of quality, and the community supports us in this endeavor no matter the price.

How do you keep your team’s morale high?

Managing a team and maintaining high morale is an ongoing effort. There is a very fine tightrope line to walk; you want your employees to take you seriously, but you don’t want to instill fear or intimidation to make that happen. It isn’t super uncommon for chefs to throw heavy or hot tools around the kitchen, yell, and use personally degrading language when giving professional criticism. At the same time, overcorrecting and coddling employees can lead to bad habits like poor attendance and low productivity.

Although this may seem like a bit of a cliche at this point, I believe that communication is the key to managing a team in a couple of ways. First, treat your team like your equals rather than your subordinates. Raising your voice or using language that personally attacks, degrades, or condescends to your employees is a good way to alienate them. I try to address mistakes with my employees by putting the employee and myself on a team against the issue at hand so that it is a collaborative effort to overcome the obstacle. Second, I believe honesty and transparency is is essential to good communication. For example, we have full transparency when it comes to salary for every person working at the bakery, (including myself) and I regularly discuss the state of the business with them as well.

Whenever I interview someone, one of the first questions I ask is, “What makes you excited to go to work every day?”. Prioritizing employees’ positive day-to-day experience on shift is, I believe, the best thing to do in order to maintain high morale, and will lead to employee retention. Employees are looking to spend their 40-hours a week in a space where they feel comfortable, and being open to employee feedback is a great way to make them feel valued. Make sure you’re practicing what you preach; if an employee comes to you with a concern, be sure to take it seriously and find a solution. Communication only works properly with followthrough.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

The restaurant industry hasn’t been the same since the COVID-19 shutdown. Foodservice is not a job that can be performed remotely. To cope, we partnered with another small business to share space (and thus overhead costs) and clientele. We began searching for a larger space to accommodate us both, and struck out about three times before 201 Market St. The space was rough to say the least, but the landlord was passionate about restoring the 95 year old building and creating something cool. I was all in.

Fast forward to May of 2023, and we had to leave the storefront that Sweet Lydia’s had existed in for about eleven years. Still reeling from the pandemic that we only narrowly survived, we had to find a way to continue the brand. However, about six months after I had first signed onto the Market Street project, the landlord sat me down to let me know that the whole project was at an indefinite stand still. My collaboration partner decided that it was all too much and closed her business.

I couldn’t find another place to go, so I rented a room in an attic above a bakery in a neighboring community. Every time I had to wash dishes, I had to carry them down two flights of stairs, then back up again after they were clean. I operated my whole business out of a single room with a single electrical circuit, meaning that I couldn’t operate more than one or two pieces of equipment at a time. Working out of the attic also meant I lacked a storefront, so I took my show on the road. I attended as many pop-up markets as I had the ability to vend at. I created subscription services so that I would have guaranteed income for a month at a time. I personally delivered orders placed locally. I found ways to get our products on the menu at other surrounding businesses from restaurants to specialty food shops. I held classes whenever possible to bring more people back into the kitchen at home, away from mundane microwaves. I threw everything I had at the business to stay relevant during this time of ongoing transition.

I did this for months until I found another solution: Mill No. 5, an indoor Main Street and basically a small business incubator. The landlord subsidized rent in order for new ventures to grow and expand. I ended up there to bide my time until my Market St. space was complete. Being in community with the other small business owners was a wonderful experience, but the hours were not conducive to running a bakery. We were only open Thursdays – Sundays, mostly evening hours rather than mornings, which is actual prime time for bakeries.

Meanwhile, the six-month building restoration project on Market Street ended up being almost three years in the making. Mishap after mishap kept happening from equipment and funding issues to almost every renovation/construction issue you can think of. The stand still lasted about another year until meaningful change began to take place in the building, and then another eight months until I finally began seeing the glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel.

I walked into the Market Street space and signed on to the project in September 2022. The project will wrap up in February 2025. I always say that there isn’t another business owner out there stupid enough to stick to a project like this. However, my space is absolutely beautiful, the location is perfect, and I’m thinking ahead to the long term. This is a space that I won’t be able to outgrow and that won’t need to be upgraded. I wouldn’t have made it here if I wasn’t willing to pivot so much and remain open to so many possibilities. There were more days than I could count that I just wanted to throw my hands up and hang up my whisk for some new adventure…But in the end, the reward justifies the price I had to pay to stay relevant with our clientele and maintain our production standards.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.pizzellebakes.com

- Instagram: @pizzellebakes

- Facebook: https://Facebook.com/pizzellebakes