Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Kirill Safin/emily Perkins. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Kirill Safin/Emily Perkins, thanks for joining us today. One of the things we most admire about small businesses is their ability to diverge from the corporate/industry standard. Is there something that you or your brand do that differs from the industry standard? We’d love to hear about it as well as any stories you might have that illustrate how or why this difference matters.

I think the mindset we took when taking on this project went a bit against industry standard in the sense that for us, building trust and community was more important than profit. Starting out as a new business, it’s a bit of a leap of faith to deprioritize profit while you’re pouring your personal savings into getting things going, but it also felt like the natural choice to make since we started this whole endeavor just wanting to make and share cool things.The approach led to a few of our favorite parts of the project – our personalized letters, lenticular trading cards, and City Sounds vinyl record.

When we were building a pre-launch list of folks for Metroboard, we offered a $3 ‘reservation’ that locked in a healthy $80 discount and priority shipping, but something about that structure felt like it was missing a personal touch. So we decided to make a pack of lenticular trading cards, one card per city, to include with reservation holders’ orders. We had the absolute pleasure of working with Marcos Abdallah, an incredible illustrator and artist, to design the cards. We gave him a write up of each city, the feeling we were going for, and the buildings and elements we thought made each city distinct. We ended up with something we’re really proud of and excited to share with people, and it’s been validated by hundreds of non-reservation holders grabbing a pack of trading cards as well.

We also assembled, wax sealed and sent thousands of letters with little train-related goodies inside to reservation holders, which took hundreds of hours to do and turned no profit. It was just the two of us going, huh, what would be the coolest thing you could get in the mail for three bucks? and then trying to make that. We have a folder of photos people have sent of the letters and goodies hung on their walls or displayed in their houses, which is exactly what we were hoping for.

Another cool auxiliary project that sprung up as we were going was the vinyl record we’re producing with another incredibly talented artist, Kyle Sloan. We met Kyle on the Boston T while we were doing our cross-country train trip to visit all of the Metroboard cities. We kept in touch, and when we ended up with a ton of audio from each city, thought it would be cool to produce a record that remixed those sounds into a little encapsulation of the cities. Again, there was no way of telling whether or not people would want the record, but it felt so obviously cool to us that we immediately jumped in. We put out an ask for additional sound recordings to folks following the project and were absolutely inundated with people’s recordings – of their local stop, their commute, their favorite subway system announcements – it’s been such a treat to listen through all of them. Kyle’s currently putting together the tracks, and we get to have these great meetings to listen to his work and tinker with album structure and feel, balancing the industrial and the unique cultural/musical underpinnings of each city’s sound.

We approached each part of the Metroboard project by saying – if we make something really cool here, even if there’s no way to prove that there’s a market for it right now, we trust that the intention and care we’re pouring into these things will show and people will respond to it.

It was an approach that took great creative energy as well as tremendous fortitude to see through, but ultimately we’ve had such wonderful responses to the work from people who have invested in what we’re doing that it’s easily made it feel like effort well spent.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

We’re a former aerospace engineer and a creative who met at an aerospace startup. We live in DTLA and watched an LA Metro station get built outside of our apartment for a few years (jackhammers and all). After having grueling 45m-1hr commutes to El Segundo for years, we grew exhausted of driving in LA and as soon as the station opened in 2023, we started to take Metro as much as possible.

It changed the way we moved around LA, the kinds of places we had easy access to, and moreover was just a more human, communal way to get around. We became big LA Metro fans and got excited about all of the other projects under construction (LA has more subway projects funded and under construction than any other city in the US).

We wanted to create something to celebrate this and made Metroboard, a live subway map with a mid-century design (it has a walnut frame and brushed aluminum face, inspired by an old vintage stereo in our living room). Metroboard connects to your WiFi and gets data on the locations of where trains are in your subway system every few seconds and updates lights to show their locations. That way, you can see the trains making their way around your city throughout the day. You can use it to catch a train, or just as a cool art/statement piece, which was really what we intended.

After making it for LA, we figured there’d be other transit enthusiasts who’d want one and figured that’d be the case for many of the other big transit cities in the US. So we set to making a Metroboard for some of the biggest transit systems in the US. We made a Metroboard for LA, the Bay Area, Chicago, Boston, NYC, and D.C., but hope to expand to other international cities in the future as well.

As big transit fans ourselves, we’re very engaged with the transit community and the history of these systems, so they were all a treat to make. We took a cross-country train trip and rode all six of the systems for a few days to spend time with them, test the Metroboard in each city, and get a personal sense for what makes each of them unique.

We’re also big believers in high quality materials and builds – the drive toward decreasing costs for most products usually means decreasing quality. We based the design off of a vintage 70s hi-fi stereo in our living room, which is primarily walnut with a brushed aluminum accent. Metroboard features almost no plastic parts, and we’re confident that both the look and the built quality will prove timeless.

Any fun sales or marketing stories?

We started from scratch to find people interested in Metroboard and building a following that’d be sufficient to launch our product. In order to succeed, we’d need thousands of orders to afford the tooling and upstart costs associated with mass production.

For everyone who found our product and signed up for a $3 “reservation”, we decided we’d send a cool hand-made piece of mail. Mail has become something of a dying art, but we’re huge snail mail fans – something physical can be very standout in the modern digital world. If it can be a unique piece of mail on top of being physical, it can really put you on the map with the recipient.

We created a mailer that consisted of a 3D anaglyph from an old movie frame, a vintage postcard, a letter printed on our dot matrix printer hand-sealed with red wax featuring our logo, all inside of a translucent envelope postmarked with the coolest stamps the USPS has released over the past ten years. We mailed these to all 9,000 folks who “reserved” our product, and we got feedback from many of them that it was the single coolest piece of mail they ever received.

As we prepared to formally launch the product, we wanted to remind all of these folks about us, so we set out to mail yet another mailer to them all. This second one was designed to be a vintage telegram from us, just to say thanks for following along with the project. We made another 9,000 of these and sent them out just before we launched.

Both of these mailers were a tremendous labor for us – we easily spent 100-200 hours hand assembling them on our kitchen table most evenings on top of our existing daily workload. Family and friends who visited us were also enlisted in the assembly line!

The material costs were largely covered by the $3 reservation fee folks contributed, but we made no profit at all on the letters, which was by design. We wanted people to get the coolest thing possible for their money rather than an empty digital ‘reservation’. Even though the reservation had real, physical perks (a sizable $80 discount, priority shipping and a free pack of our custom-designed lenticular metro trading cards) those wouldn’t be immediate, and we wanted people to have a tangible artifact from us the moment they invested in our project. The relationship between businesses and people has gotten so impersonal and borderline exploitative that we wanted to make sure it was clear that wasn’t who we were.

Ultimately, we didn’t know if these letters were going to make a difference. That was challenging to swallow, considering we essentially spent all of our evenings and weekends for months putting these together and drawing down our checkings account, all for the hope that people would appreciate the effort. But ultimately, we did have a strong belief that this kind of intentional connection is both so lacking and yet a need so deeply felt that our efforts would be make a difference.

When we did launch our product on Kickstarter, we ended up raising $1,000,000. We were constantly pushed towards hiring “experts” and consultants to help us, but we had faith in our approach and in the work we were making, and it seems rightfully so. While we will never be able to determine how much of that impact came from the letters themselves, we feel that they made a difference.

The marketing story is simple – make cool things, share them with your supporters, and prioritize expressing your gratitude above making a buck.

Okay – so how did you figure out the manufacturing part? Did you have prior experience?

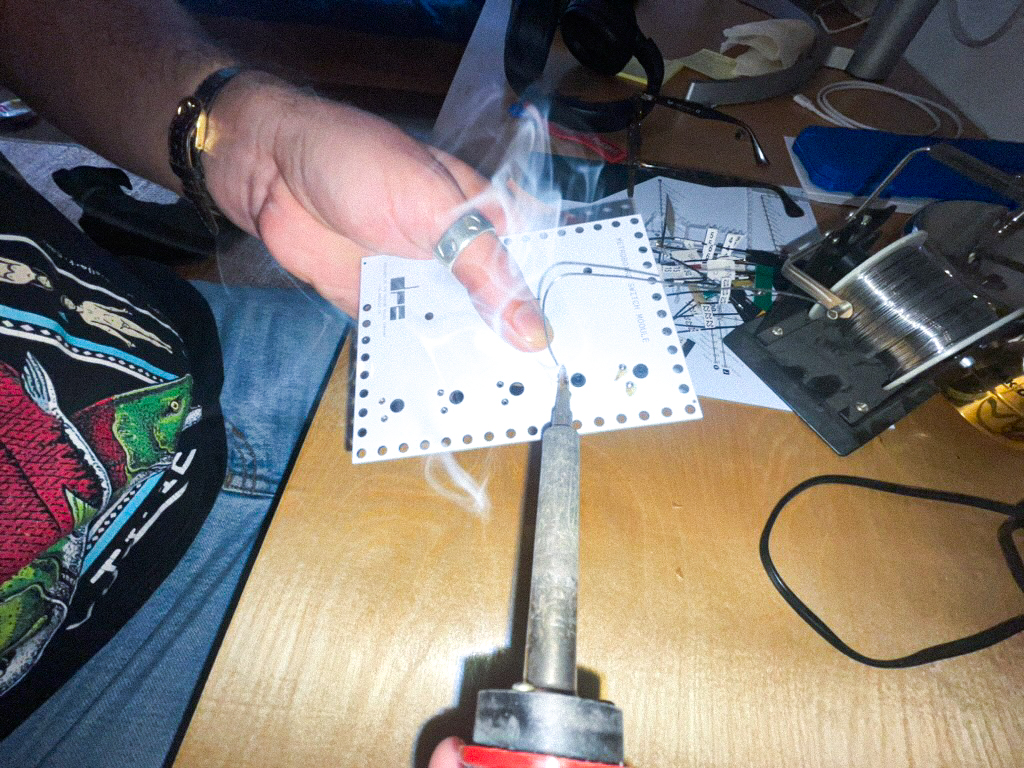

One of us is an engineer coming from Aerospace with about five years in the industry and yet more years making and building projects in high school and college. Because of that, we had a good sense on how many things are made (plastic parts, metal parts, circuit boards, etc) which gave us a solid start.

The most difficult aspect of manufacturing for us has been the finish (the detailed final appearance) and technical feasibility.

For the first – finish is exceptionally important, especially for a product that is focused on design – so getting it right is one of the most important aspects of manufacturing. Materials like wood are particularly challenging for this, since there are so many species, colors, finishes, and grain variations. Others, like metal, are more controlled but still can have a lot of variation – one manufacturer performing brushing can look different than another – in a way that’s substantial enough to impact your product. There is no trick to this besides to find as many reasonable vendors as you can, sample their finishes, and find the one that works for your product in terms of look and cost. We did this, and got lucky finding most of our vendors after just 2-3 tries.

As for the second – technical feasibility – this is a nuanced one that can really make or break your approach. It may be possible to manufacture a part one particular way, but it can be that most manufacturers don’t have the equipment to make it quite like that, or otherwise that, though feasible, it is too complex and expensive to do on a large scale. Bumping against these walls can only be achieved by actually starting the process, making some designs, sharing them with manufacturers, receiving feedback, and iterating.

One of our best decisions was to work with actual mass-volume manufacturers from the beginning to make our first prototypes. Instead of making something by hand which may not look like the final product (or be potentially costly to make, once you start quoting) we made everything through the actual manufacturers. This was a much more costly way to make the prototypes, but we knew that we could make whatever we made at scale, and we always made sure that the volume pricing worked out. That way, you’re always comfortable in the knowledge that the prototype you’re creating and seeing is one that can actually be made.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.designrules.co

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/designrulesco

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/designrulesco

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/designrulesco

Image Credits

Emily Perkins Rock, Kirill Safin, Chiara Dollak