We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Amy Miller a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Amy , appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about when you first realized that you wanted to pursue a creative path professionally.

I originally studied political science and never expected to end up making documentary projects. I didn’t attend film school, but I was deeply moved by the idea of documentaries as a powerful way to transfer knowledge—not just as information, but as lived experience. Documentaries are, in many ways, political essays for me, where the message is always backed by a sincere quest for truth. After years of activism and union organizing, I found that filmmaking offered a new dimension to my work—a way to reach people on a more emotional and visceral level. Since 2006/2007, my documentaries have sought to shine a light on pressing issues that often go underreported, always driven by that deep commitment to justice and change.

Amy , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

Filmmaking has been an incredibly powerful way for me to merge my activism with art, using documentaries as a tool for critical analysis and popular education. Before I started making films, I was deeply involved in the anti-war movement, particularly with a group in Montreal called Block the Empire. At the time, I was shocked to discover there was no documentary addressing Canada’s military-industrial complex and its role in war profiteering during the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq. That realization, coupled with my background as an organizer and educator, drove me to pick up a camera and start telling these stories myself.

Documentaries offer a unique kind of accessibility. They allow people to absorb information quickly and easily—much more so than traditional academic channels. I’ve always been inspired by the idea of Paulo Freire’s ‘ah-ha’ moments, where people connect the dots and see the world in a new way. That’s the heart of my work—taking complex topics like carbon markets, war profiteering, or systemic injustice and turning them into something accessible, understandable, and ultimately actionable for viewers. The Carbon Rush, for example, looks at the global impact of carbon trading, showing how these markets give monetary value to carbon emissions and exploit communities.

I’m deeply inspired by the public and the people who watch my films. There’s nothing more rewarding than hearing that someone has learned something new from one of my documentaries, or that the film helped them articulate ideas they’ve struggled to express before. We’re often not getting this critical analysis from our schools or corporate media, and I see my work as a tool to help turn knowledge into action and engagement.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

In my view, society can best support artists and creatives by fostering environments that prioritize accessibility, collaboration, and community-based initiatives. First and foremost, we need more public funding for the arts—supporting independent filmmakers, visual artists, musicians, and other creatives is crucial for a thriving cultural ecosystem. This means increasing grants and subsidies that allow artists to work without constantly worrying about financial survival.

We also need more spaces for dialogue and debate. Universities, community centers, and platforms like Cinema Politica play a huge role in this by creating venues where people can engage with art that challenges societal norms. Support for grassroots projects is essential—things like crowdfunding platforms (like Kickstarter) and cooperative models where the community directly invests in the success of artists can be incredibly effective.

Education systems should also emphasize arts education, not just as an extracurricular but as a core component of learning. Creativity is not a luxury; it’s a vital way for people to engage with the world around them, understand complex issues, and develop critical thinking skills. Lastly, society should foster a culture of respect and value for the work that artists do, recognizing that the arts are not just entertainment but a way to provoke thought, inspire change, and connect us to one another in meaningful ways.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

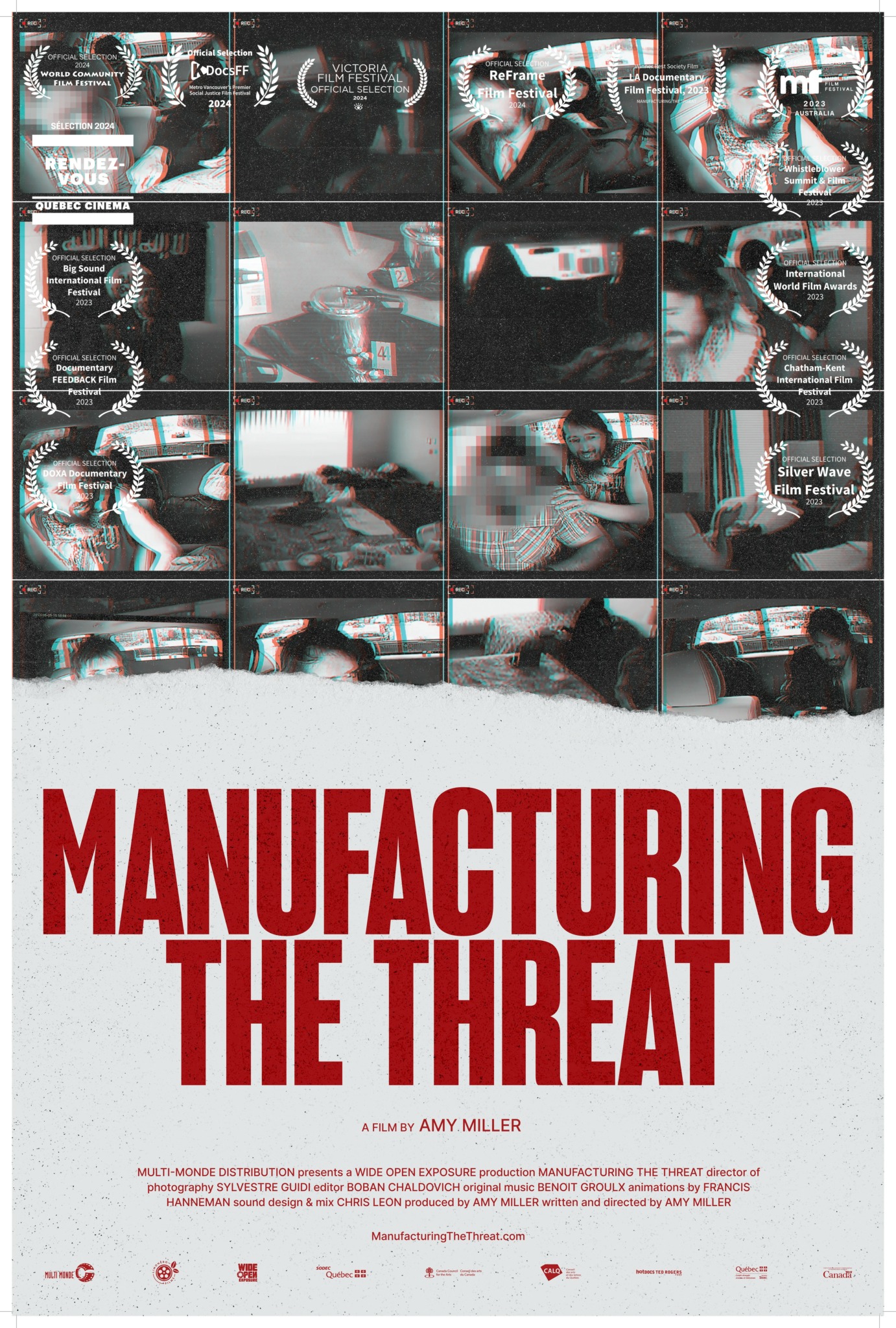

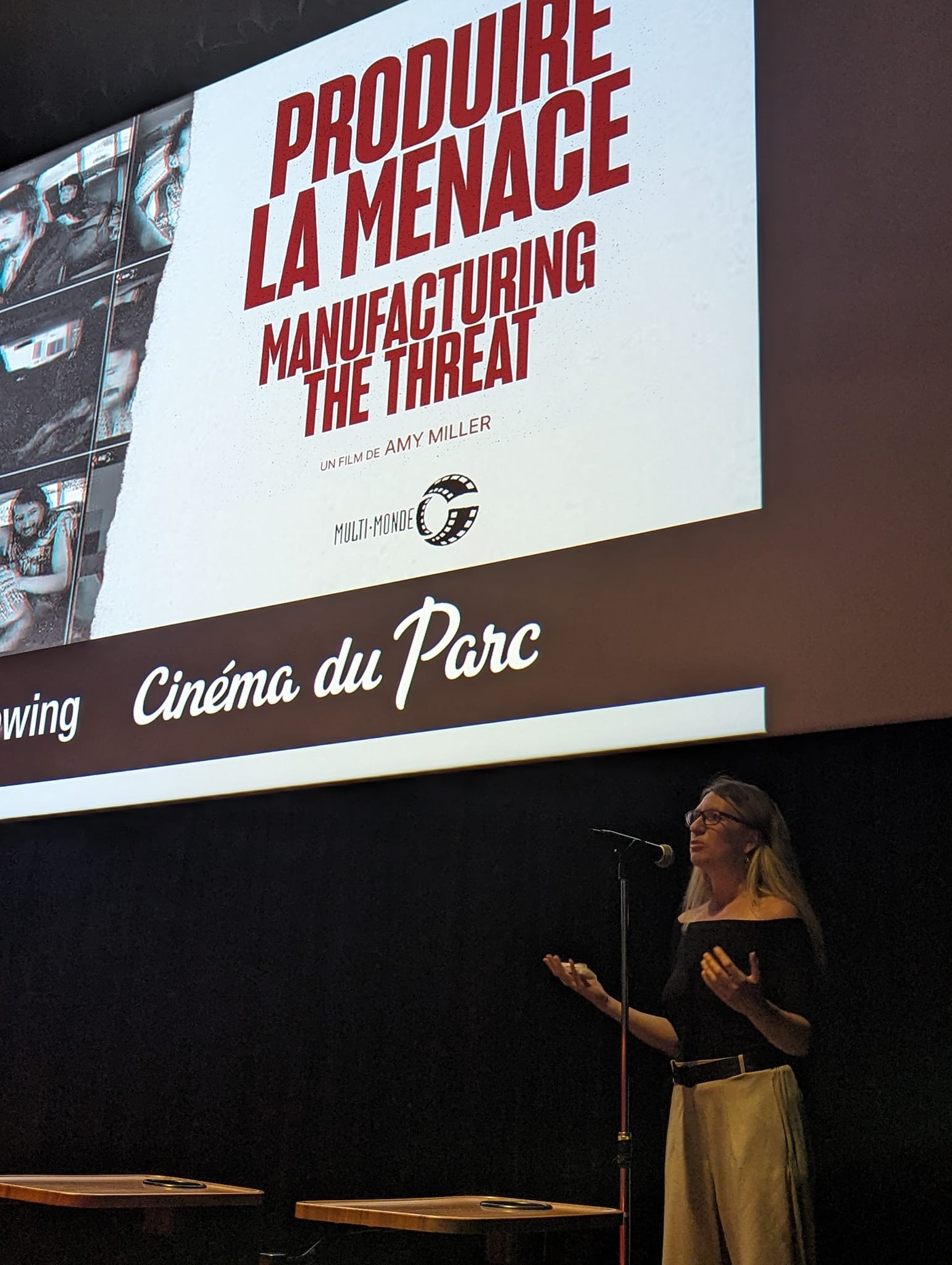

Securing funding for ‘Manufacturing the Threat’ (2023) was a significant challenge, even though my previous documentaries had been well-received. The film explores complex and controversial issues around entrapment and how law enforcement manufactures threats under the guise of national security. Because of the sensitive nature of the subject, traditional funding avenues were hesitant to support the project.

In response, I took a hands-on approach to financing the film. I self-funded the project by working on side projects as a director and producer, directing the cash flow into the project. It was a tough and demanding process, but I was committed to seeing the film through because I believed in its importance.

It reinforced the idea that when you’re passionate about a project, sometimes you have to create your own path to make it a reality.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://wideopenexposure.com/#films

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/wideopenexposureproductions?mibextid=LQQJ4d

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/amy-miller-montreal?utm_source=share&utm_campaign=share_via&utm_content=profile&utm_medium=ios_app