We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Sara Fellini. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Sara below.

Alright, Sara thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. I’m sure there have been days where the challenges of being an artist or creative force you to think about what it would be like to just have a regular job. When’s the last time you felt that way? Did you have any insights from the experience?

I work as a playwright, performer, set designer, costumer for my own company spit&vigor (www.spitnvigor.com) and various other small-budget theater companies in New York City – but because I’m working with small budget spaces, I do have to keep a regular part-time job to pay my rent. I’m lucky that I’ve navigated my way to a position in the arts, as an assistant manager in a studio space, as well as running my own small studio space. But in the past I’ve also bartended, waitressed, I even programmed hearing aids for a weird brief moment. I am unfailingly grateful to have worked the service positions particularly because working in service, in and among kitchens and bars, gave me qualities that I use to this day on and offstage: quickness on my feet, quick-thinking skills, practicality (very rare to come by in some theater spaces), and humility (equally as rare). I will never take money, or status, or position for granted in my writing, or in my production design. I think about status when I look at fabrics for costumes, I think about practicality when I’m designing sets for a travelling production, I’m incredible at stretching a dollar to the moon because I have no backup plan; I have to.

My passion is theater, but sometimes theater can get kind of pretentious and removed from the people, which is the furthest thing from what should be happening, especially right now. Theater, along with maybe live music, has a unique ability to bring people together in the moment, in one room, connecting on a human level. You just need to have fun with it, and not be so serious. I do think the pretentiousness can be due to a lack of working class people in the field. Theater can be so expensive to produce, and we’ve started to think of it as just another job, so that the only people that can afford to produce mainstream theater are people with enormous budgets – people with money. It concerns me that we’ve gotten to a position where we expect all of our art to be delivered to us by or at least via the rich.

But to answer the actual question, I am exceedingly happy being both a creative and a workaday grunt – in fact, during our last production, I stopped and really digested how happy I was, to be able to do the things that I love, and to be given the gift of working very very hard for it. Sometimes we forget that hard work is a gift as well, if you come at it with passion and intention. I have worked my fingers to the bone for ten years, sacrificed quite a lot, to build my small company from the ground up. And I’ve kept grounded by continuing to work, and keeping friends who work ~*real*~ jobs. It’s something practical to focus on. A lot of anxiety is produced when you fight the work, fight hard conversations, fight difficult decisions. But if you dive into your life, work hard, and play hard, you can release a lot of kinetic potential and free your mind. Which, is the truest form of happiness. When I asked what he wanted most in life, my dad always used to say “peace of mind”, which is a phrase I had a hard time wrapping my head around until I was an adult. But that is what’s been given to me, if I can keep it.

Sara, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

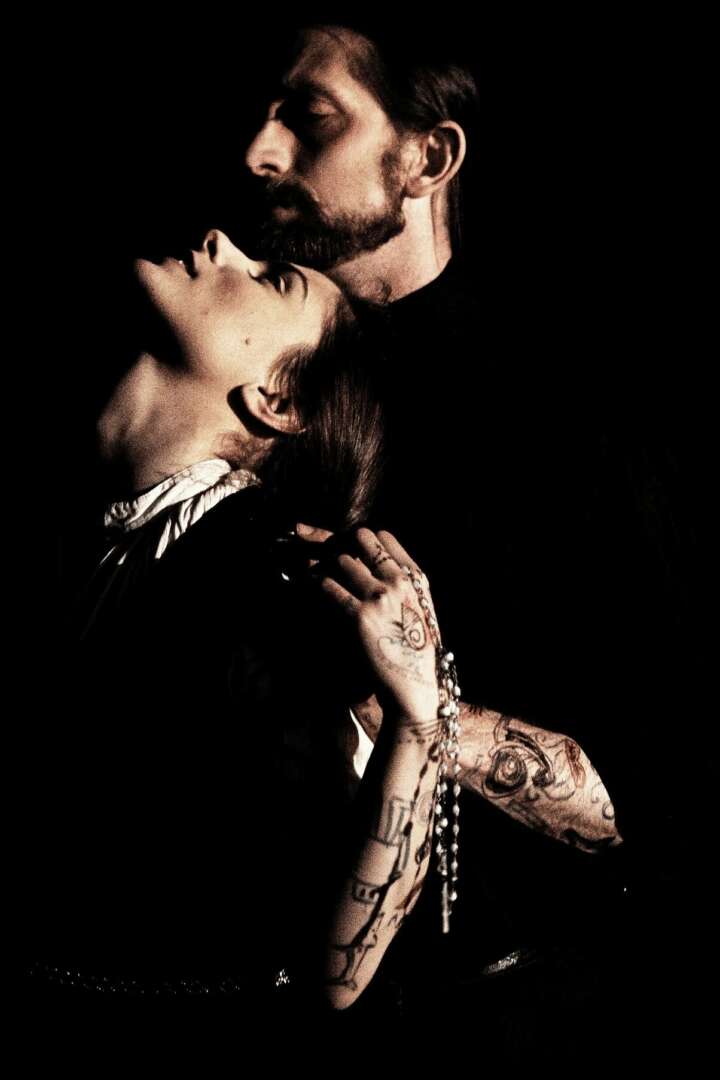

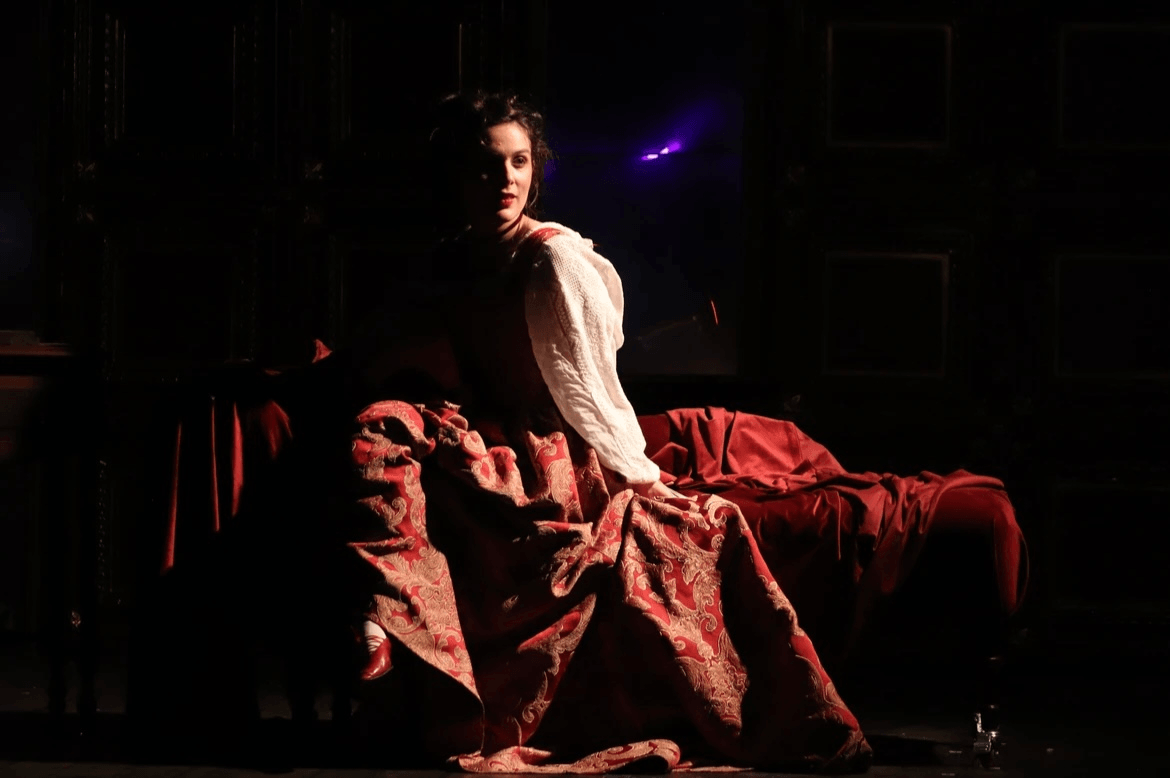

I run a small independent theater company based in the West Village of New York City, called spit&vigor theatre company (www.spitnvigor.com). Our tiny theater space is called spit&vigor tiny baby blackbox theatre, and we produce our own productions there and also offer subsidized rehearsal and performance space for other small-budget companies. It’s a 19×26 feet blackbox theater, where we produce deeply intimate productions for small audiences of about twenty people. We use the limitations of our space to our advantage, creating what we call “embedded” style theater, where the audience is basically a fly on the wall of a room where the action is happening. One of our plays, ANONYMOUS by Nick Thomas, has the audience sit in a circle among members of an addiction support group, but the support group members are in 1992 and smoking (fake, but realistic) cigarettes with their ashtrays and styrofoam cups of coffee. Attention to detail is paramount, so I really went out of my way to source 1990s costumes and props, so it feels like you’ve time-travelled, or that you’re sitting next to a ghost. Another production, GRIND by Z Quinn Reynolds has the audience sitting in a waiting room with individuals in a dystopic America where citizens are gruesomely ground into sausage to feed the population by their 18th birthday if they don’t meet a comically vague standard of excellence demanded by the visibly crumbling “homestead” state. The audience is not invited to participate, which sometimes can lead to self-consciousness, but they are right in the middle of the – sometimes intimate, sometimes gruesome, sometimes violent – action.

As a theater company, we also perform at The Players (a historic mansion) and other site-specific indoor spaces. We’re quite proud of the work that we do that connects people, and explores hard personal and political questions, and doesn’t just fall in line with the status quo. Our plays are usually historic or time is otherwise non-standard, so while we give a welcome respite from cell phones and social media (none of our mainstage plays have ever featured a cell phone except to immediately destroy it), we also present difficult situations that work to question some of the lockstep beliefs people can have today. Questions about money and art, about who gets the money and where does it come from – for instance, in our play NEC SPE NEC METU, the Baroque painter Caravaggio rails against censorship and the rich elite to his own utter and bloody destruction. Questions about putting marginalized demographics on a pedastal, whitewashing their humanity – for instance my play THE WAKE OF DORCAS KELLY builds up the modern feminist image of a take-no-prisoners, wild, free, sexual heroine with a rad bordello madam who shot a man in the street and was hanged for it, only for her friends to start discovering the dead bodies of murdered young boys hidden in trunks in her chambers during her wake, leading them to question what horrors they overlooked to support their own interests. Speaking of overlooking evil, we regularly perform THE BRUTES by Casey Wimpee in the historic home of Edwin Booth (brother to John Wilkes Booth). That play explores the “first Thanksgiving”, or really, the last big family dinner of the famous Booth acting clan before Wilkes assassinated Lincoln – and how difficult and petty of a person he was, but similarly how the family alienated him and turned a blind eye to his increasing radicalization. It mirrors the disaffected men of our current generation, and questions how much responsibility we have for isolating and alienating difficult young men. We don’t condescend to provide answers to these questions, which honestly is kind of old-fashioned of us, but I think it’s a service to provide that kind of thought-provoking work right now when so much – theater, TV, and movies – is watered down or patronizing, and ultimately, divisive.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I have a defiant streak, and I was raised very independently, so it was surprising to me how much I had to unlearn about the film industry, in order to even be happy, let alone successful. Theater is emotional intimacy, at a distance, that blurs reality and focuses on inherent truths. Film is subtle, but the camera is in your face. It sets the standard for beauty, and also for what passes as, comfortable, accepted, normal. I had a gorgeous friend who worked in film and she had to wax her face to get rid of the little, absolutely invisible, fluffy, I guess you’d call them “hairs” on her cheeks, and it made me think of nuzzling my mother’s face and how she had little blond fuzzies, and how awful it is to be told you have to rip part of you off in order to fit a standard. And even if I consciously think “that’s ridiculous”, how much of it sticks in my craw, or bleeds into my psyche? When I look in the mirror, how many times out of ten do I see my beloved family’s inherited features, and how many times do I see an old Italian strega? My personal style has always been off-beat, not for any particular reason, really I don’t actually understand how to dress “normally” – I can see what people are doing, and while I don’t mind standing out, I’m not doing it intentionally, something just doesn’t quite click for me. The level of impatience and snide…ery I dealt with when providing *my own clothes* when I briefly did extra work because I didn’t have a suitcase full of normal clothes prepared for whatever scene they were doing was incredible. Truly galling. Similarly, I don’t cut my hair, and generally people love it (or hate it) because it looks like medieval princess hair, but I honestly can’t name a single actress who has hair like mine, even children, with no product or styling or expensive haircuts or dye, since probably the mid-1990s. It’s subtle, but it matters, possibly even more because it’s subtle and gets under your skin without you ever digesting it consciously. Same with makeup – how much do women have to spend on hair, makeup, clothes, that men don’t have to spend? Even further, how much more do black women or women with very textured hair have to spend? That’s in terms of both time, energy, brainpower, and money. We can enjoy beauty and regimens and self-care, but when it’s applied in this panicked, self-conscious Lady MacBeth way of “out out damn spot”, as if you did something wrong, or you’re going to be exposed, or you should feel guilty about your own blemishes, which it is in film because your very livelihood depends on it, we should rethink our relationship to beauty and the flaming hoops we’re willing to jump through for a job that will keep us comfortable for a month or two.

I gave up on film pretty quickly becasue the kind you can pay your rent with doesn’t let you get away with an inch of individuality, or idiosyncracy. Because the visuals are rarely squishy or representative, like a blackbox standing in for a living room, you have to represent everything so unflinchingly, and honestly, and I guess I don’t need that kind of realism. And we don’t need to endure it extending into our personal lives. I had the choice of getting a couple of like, I literally have no idea – business suits? Like those tight business bodycon dresses? And paying three hundred dollars for a haircut, or just bartending. So, I bartended, and I’m glad about it, ultimately.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

I know a lot of people want the government to support artists, but I don’t know how much I want the government involved in art, to be honest, particularly as we stare down the barrel of a potential second Trump presidency. But under any administration, even if the government isn’t proudly evil, it’s still political and powerful. So government grants are not an easy solution in my perspective. Particularly since I’ve been on grant funding committees where my fellow participants laughed at me when I tried to bring up the socio-economic intersection of certain art forms (punk rock, for example), as if I was joking. And this was on a committee that was honestly really conscientious about compensating applicants for their time writing the grant, for example. But still, that experience gave me a deep mistrust of non-profit and government grants, and how even they are just coming from the rich elite with a sort of distant understanding of how the working class live. If society could somehow provide a universal basic income to all people without the cost of living just rising to meet it and making it useless, I would be for that. Or just totally blind government grants to all artists.

But really I’m not against art being difficult to manage, financially or socially. I think it’s an absolute privilege to get to work in art, and it should be hard to do. We might get some better artists if actors were still treated like the scum of the earth – you’d really only get the people who couldn’t live without it. And truthfully, there is a basic dishonesty in acting which does make it, I don’t know- dishonorable, in a way that’s interesting. It depresses me when you’re speaking to say a Broadway chorus actor, and they talk about their PTO or something, or when SAG actors get petty about dinner lines on set. I know how that sounds, but when you look at life, actual life, it is such a privilege to create art for a living. And not everyone has the vision or the ability or creativity to do it well enough so that other people pay for it. And I come across so many artists that are just, good. They’re not passionate, they’re not creative, they’re not inventive, they’re not contributing to the culture, they’re just good at emoting and so they think they should be paid for it, and I don’t necessarily think that’s true – but moreover, it gives the rich corporate machine more chuff to grind up and spit out to create mind-numbing, meaningless art that is the modern opiate of the masses, because they’re using dispassionate, zombie-minded people as their fodder and their army.

So honestly, the best solution to me would be to encourage art and creativity for everyone, in everyday life. To support systems of social justice and pay equity so that people just have more free time to practice art, to give everyone more opportunities to create, and then to honor, venerate that type of community creativity. Not everyone needs to make money off of art, and if we lived in a more fair society, we would think of acting, singing, dancing, as an expression of your humanity instead of a hustle. You don’t need to make money off of everything. You can do things just because you enjoy them, and you should have time and space and energy to do them, and I think we need to encourage that way of thinking.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.spitnvigor.com

- Instagram: https://instagram.com/spitnvigortheatreco

- Facebook: https://facebook.com/spitnvigor

- Other: https://sarafellini.com

Image Credits

Giancarlo Osaben, Yvonne Allaway, Caitlin Ochs, Nick Thomas