We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Christin Fanelli a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Christin, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Learning the craft is often a unique journey from every creative – we’d love to hear about your journey and if knowing what you know now, you would have done anything differently to speed up the learning process.

I am happier in my job than I ever thought possible. That’s not to say there aren’t times where I’m incredibly frustrated by my lack of power, or angry that I’m still not in the role I want, or tired from the lack of student engagement. But at the end of the day, I go home feeling fulfilled and I get up the next day excited to do it all again. When asked as a kid what I wanted to be when I grew up, I always had a different answer. They always had one thing in common: science. I wanted to be a vet, or a doctor, or if you asked me after my first-grade field trip to the aquarium, a dolphin trainer. I didn’t realize how much I liked art until I was a junior in high school. But when I fell, I fell hard. I remember asking my high school art teacher, Mrs. Fagan, how I could make art a career. I had no interest in being a famous artist. I didn’t need to be represented by a blue-chip gallery, or have my work seen in famous museums. I still don’t. I just loved art and wanted to help others learn about art so they would love it too. Maybe one of those students would go on to be famous. At the very least, I want them to come out of my class appreciating art more than when they walked in. That’s what I do, and I couldn’t be happier.

I have on several occasions wondered what it would be like to have a different job. I think about how nice it would be to work at a traditional nine to five where I can go home in the evening and not worry about anything. A job that isn’t so entangled with who I am at my core, my hopes, and my dreams. I had a short, though intense, crisis of conscious where I considered going back to school to do something, anything that had more stability. More stability in terms of hours, income, and job security. After many tears and conversations with my peers (and I can’t forget several tear-filled calls to my mom) I realized that there was a reason I put so much time and hard work into my career. This is what I love to do. It may be hard and uncertain, but living my life any other way would be so unfulfilling that I think I’d lose my sanity.

I don’t think this career path is for everyone. You must be willing to accept that you will never be fully appreciated for all the work you do. People will always complain that your art costs too much or say they don’t get it. You will have people who will dismiss your art. You will never have enough time to turn every idea that exists in your head into a finished artwork. You will never be paid your worth. You will always have students who test your patience or who disrespect your time. You will always have students who fail no matter how hard you work to get them to succeed. You will always have a student who gives you a bad review on your evaluations. You will purchase your own supplies that end up broken, stolen, and misused. You will have administrators who provide no support, leaving you to fend for yourself. But if this is truly what you were meant to do, you will go home at the end of the day feeling fulfilled and ready to do it all over again. You will never feel happier than you when you see someone enjoying one of your artworks, or when a student becomes enthralled with the world of art.

Christin, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I am an active artist and art educator. I have dedicated the last 14 years of my life to learning as many visual art mediums as possible, while simultaneously developing a deep understanding of printmaking techniques.

From the time I was 16 years old I knew I wanted to be an art teacher, the specifics of this changed over time but my main goal remained the same. Unlike a lot of young people, I went into college with a clear goal; however, I severely lacked the skills needed to accomplish it. But I had a plan and I set off to accomplish it, even if I took the scenic route.

I was incredibly fortunate to be introduced to printmaking in high school. That’s where I made my first relief prints, including several reduction prints. I fell in love with the process and knew I wanted to continue to learn more about the medium when I entered college. I was a horrible student in high school, so I started my college career at my local community college. Little did I know this would be a blessing in disguise; as this community college is one of the few that offered a wide range of printmaking courses. By the end of my first year, I had been introduced to the basics of lithography, etching, relief, and a few digital based processes. The whole idea of this step-by-step process that had to be meticulously followed appealed to my obsessive-compulsive brain and the science behind each process fulfilled my love of science. The often-random problems that would arise were a puzzle lover’s dream. Still, none of these processes fit quite right.

After transferring to Towson University, I took my first screen printing(serigraphy) class with Anita Schreibman. I found my home. Everything about the process of screen printing felt right to me. Just like every student my prints were crooked and off register. I had fingerprints everywhere and the backs of my prints had ink smeared all over them. But to me it didn’t matter to me, I was making art! Towson University started as a teachers’ college and my plan was to be an art teacher. It was here when I discovered that my love for teaching did not outweigh my lack of tolerance for teaching children. The more time I spent working on my bachelor’s degree the more I discovered my love for the rigorous world of higher education. I yearned to be in the type of environment that pushed people to strive for greatness. I wanted the rigor and challenge of teaching adults who were (in most cases) in these art classes because it was their passion. So, my plan shifted, and I decided I wanted to be a college art teacher. This meant I need to complete a master’s degree to even be considered for such a job. My professors advised me on how to find the best programs for me. They helped me build a portfolio and admission documents I was proud of.

I received several offers but Ohio University offered me a great funding package on top of it being one of the best printmaking Master of Fine Arts programs in the country. So off I went to Ohio.

Here I was introduced to a whole new caliber of printmaking. Our studios covered an entire floor instead of being crammed into a single room. I was working with some very well-known printmakers. We had visiting artists every semester who came in and shared their techniques with us. I made friends with other printmakers and artists, developing relationships I will have for the rest of my life. I had three years to absorb as much information as possible that culminated in the best work of my career at that point. It’s here that I had the biggest struggles of my life. On several occasions I considered dropping out, thinking I wasn’t good enough to be part of this incredible opportunity. It’s the imposter syndrome, it’s something everyone deals with. You also have some professors who could be really excited about an artwork who push you to continue in that direction, while other professors believe the piece isn’t working and push you in a different direction. It’s like you’re constantly navigating a horrific storm out at sea. You have no landmarks to guide you. No help is coming, and you must attempt to save yourself. I had to make several seriously awful prints first, but I got there. All it took was time and thousands of prints (and several thousand dollars of paper), but I developed the watercolor style monoserigraphs that I’m known for today.

While working on my master’s degree I found my way to the world of disability studies and discourse. This is what my work is based on. I’ve been disabled all my life but never felt comfortable claiming it as part of my identity. I had this idea that I wasn’t disabled enough to be considered disabled. The ableist mentality was so engrained in me and society. We have an idea of what a disabled person looks like, and since I didn’t fit that mold, I wasn’t disabled. My disability affects every facet of my everyday life. Once I claimed my disability, as part of my identity, I felt empowered to share my experience with the world. I had finally found my artistic voice.

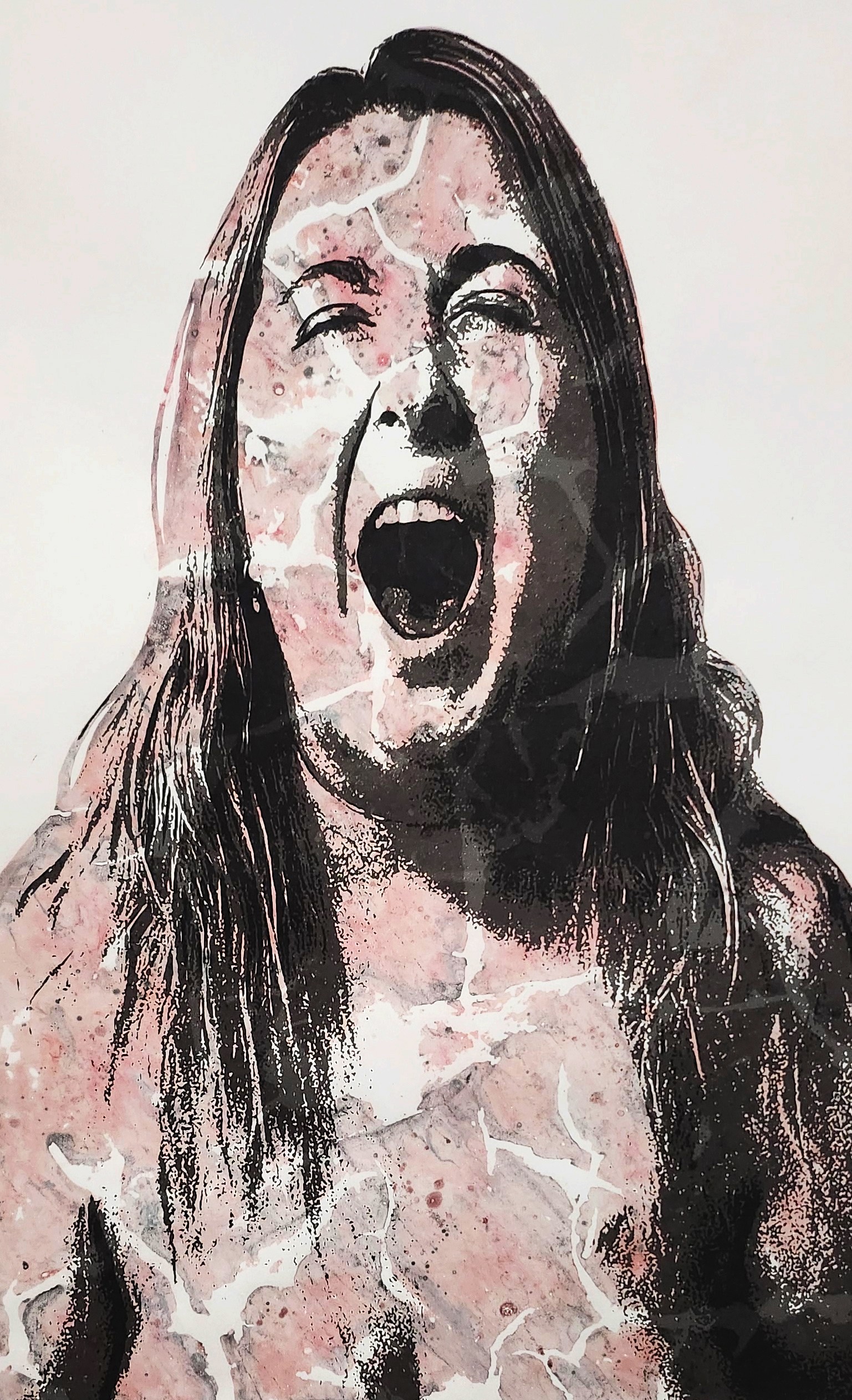

I make work that discusses the perception and portrayal of persons with disabilities in the contemporary United States. In my work I create an environment that disabled people will know and recognize, and able bodied people will learn and observe. In the gallery I use a disabled lens for nondisabled viewing. This strategically allows the disabled subject to redefine the ableist stare. The viewer holds power in staring, without the fear of the subject staring back. This creates a guilt-free observance for the nondisabled viewer while simultaneously commenting on the historically expected oppression of people with disabilities. My work rejects the temptation to value the body as anything other than what it is; rather I choose to embrace what the body has, and will become, based on the demands on it. With my work I strive to initiate the discourse to address disability as something other than personal misfortune or individual defect but rather the product of a disabling society and built environment.

As I’ve found my place in academia, I’ve fused my passion for disability discourse with my love of education. I’ve continued to research issues of access, diversity, and outcomes of students with disabilities in higher education. I aim to find practices that support the retention and success of students with disabilities. I want to expand the conversation about disability in higher education beyond the traditional narrative of the deficits of people with disabilities, legal compliance, and academic accessibility. It’s time we address and correct the realities of the inequities in higher education for students with disabilities.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

For me it’s about more than being an artist. I always classify myself as an art educator. I could create art all day long and be happy, but it doesn’t have the same reward as teaching others to make art. I’m a great artist, I know I’m a great artist; but giving students the chance to grow their confidence and to learn the skills to become a great artist is so much more rewarding. I love the moment when something clicks, and you see a look of understanding wash over a student’s face. Or when they get excited about learning something new. When they come into class excited to learn, or when they just can’t wait to share with me and their peers what they have been working on.

I want to change the face of art education. I have several professors from my time in school who had a huge impact on how I teach. But overall, I want to turn the education system on its head. In the last several years, higher education has become a commodity. Students pay and expect a degree, even when their course work isn’t up to par. That’s not the only problem, we have limited art classes in a way where the mix of skill levels isn’t conducive to the learning environment. I’ve seen more and more classes being offered to a wide range of skill levels to limit the number of course offerings and to make art departments more economical, among other reasons. When you have novice students in a class with experienced students, you’re forced to either turn down the level of difficulty to match your novice students, (causing the experience students to be bored), or you teach at a level that challenges your experienced students, (but your novice students can’t keep up). Students become frustrated, overworked, start to give up and then we lose them. Schools are losing their art departments and sometimes it feels like no one is working hard enough to stop it. Maybe they’re tired from years of fighting, but I’m here. I’m fresh and new, and ready to take over. I want to step in and force the change that’s yet to come.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

Three months after finishing my master’s degree I became critically ill and spent 3 months in the hospital. Due to the illness I was facing, and all the complications, I had a cerebellar stroke that left me with minor deficits in my balance and coordination. For reasons unknown, I lost three to four years of memory. All the skills I learned and memories I made during grad school were gone. Grad school was easily the hardest thing I ever had to do, but it was also the most memorable years of my life. Maybe I’m glamorizing it as I think about all the memories I lost, but I mourn those memories every day.

Seven months after leaving the rehab hospital, and completing three more months of outpatient rehab, I was able to get back into a printmaking studio. I was still living in Athens, Ohio and was able to work with one of my mentors to get back into the printmaking studio over the summer. Over the course of 10 weeks and 15 prints I was able to relearn some of the skills I mastered while working on my graduate degree. Being in a familiar space was invaluable to me as I picked up the skills I had previously mastered. I am incredible thank full that the area chair, Melissa Haviland, worked with me to get access. Not to mention all the emails I sent asking questions as I relearned what I previously knew. I was starting nearly from scratch to relearn the monoserigraph techniques that are instantly recognizable in my work.

In addition to relearning all the techniques I had to relearn how to move my body. Even holding a squeegee felt foreign to me. All the “printmaker muscles” I had built up over more than a decade were gone. Things as simple as coating a screen felt awkward. I had to relearn how to maneuver my body while holding a screen, how to get my hands to communicate to pull a squeegee at the same speed on both sides. How to keep from falling as I stepped on and off a step stool to reach my screen on the vacuum table. I used to navigate any print shop with ease but I felt like a novice taking their first intro to screen printing class. I’m still not where I used to be, but I’m getting there.

All my friends and cohort moved on to bigger and better things. Some were working as master printers, in residencies, teaching, or even in the process of starting their own printshop. They were moving forward with their lives and careers. I was static. I had not started doing the things I dreamed about. I had an extreme crisis of consciousness, and even considered working on a business degree (ew), giving up my dream for a more stable job that didn’t require the physicality I now struggled with. I was terrified that being a year behind meant there was no future for me. I was afraid hiring committees, seeing the one-year gap in my resume, wouldn’t take the time to ask what had happened, and just pass over my resume for others who applied for the same job.

One year after landing in the intensive care unit for my “medical misadventure” I started teaching at not one but two universities. Id like to think that the extra time prepared me and made me a better applicant. I know that I am a much better professor because of all that I experienced. I’m better equipped to emphasize with my students and am significantly more patient. After everything that happened, I believe I’ve caught back up to my peers and have a good start to my career.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.christinfanelli.com/

- Instagram: @christinfanelli

Image Credits

All photos are my own.