Newsletter

Sed ut perspiciatis unde.

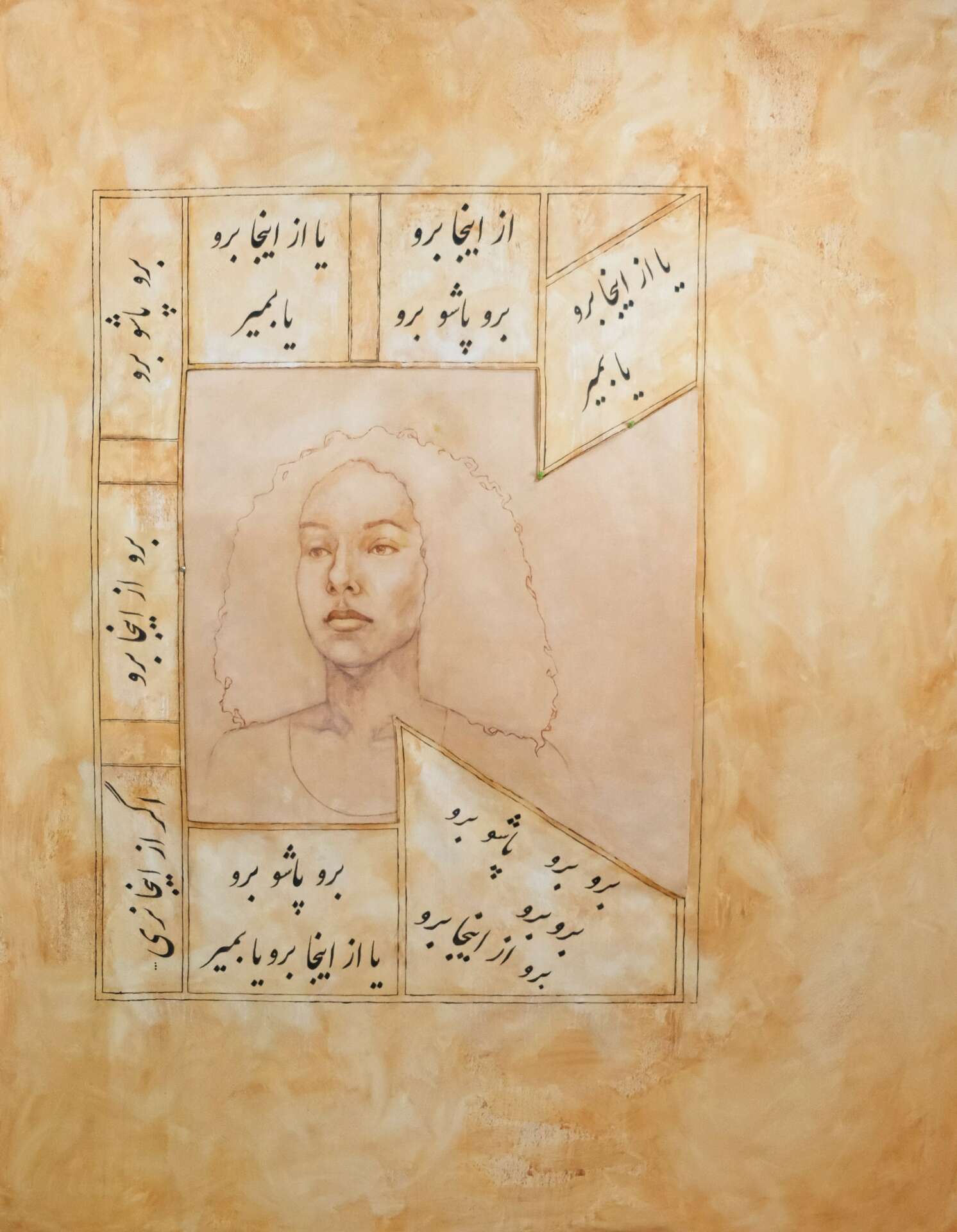

SubscribeWe’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Ghazal Ghazi. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Ghazal below.

Ghazal, appreciate you joining us today. We’d love to hear about a project that you’ve worked on that’s meant a lot to you.

In 2022, I worked on a ceramics series called “Spillages” which reinterpreted Iron Age ceramics from the Iranian plateau. These beak-spouted earthenware vessels are thought to have been used either for ceremonial purposes, burials, or to carry wine. The distinctive curvature of the vessels resembles the necks of birds, and traditionally each pot only had one beak since the elongated, protruding form results in a more fragile pot.

At the beginning, I made some pots with just one beak, but then I began to add additional beaks. In this way, I was experimenting with form and functionality while pushing physical limitations. With each beak that is added, the liquid inside the vessel has an additional channel, allowing the vessel to free its contents in a controlled manner without spilling over from the top. However, each beak that is added also means that less water can be contained in the vessel – so its holding capacity is less. The heavy, elongated beaks test the physical integrity of the clay, increase its vulnerability, and leave the vessel at greater risk of breakage with each beak that is added on. I made a couple vessels with two beaks, and one fairly large pot with three beaks, which was an exciting if not anxious process that had me coddling every foreseeable need of the clay pot to increase its odds of surviving the firing process.

This series was created in the wake of the Woman, Life, Freedom movement after the brutal state murder of Mahsa Jina Amini in Iran and the ensuing state repression, murders, kidnapping, torture, and incarceration of protesters. Within the larger context of intergenerational trauma, (im)migration, carceral regimes, police brutality worldwide, and the violence and inequality wrought by white supremacy, patriarchy, and global capitalism, these vessels ask: how much force can the collective human body withstand before spillage turns to breakage?

Ghazal, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

In your view, what can society to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

Experimentation, risk taking, and exploration are at the heart of creativity for me. I think this approach is directly opposed to capitalism. Whether out of financial necessity or personal values, I see a lot of artists commodifying their work, and even though I feel the financial pressure to do so as well, turning art into a commodity or a product has always grated against me. Are we just here to make more products to be bought and sold? I love showing the messy, gritty process behind each work of art. This pushes back on the collective obsession with only showing the clean “final product” which sanitizes and obscures the dynamic terrain of the artistic process which is often emotional and filled with uncertainties. This is where I think creativity really lives. To this end, mistakes are an integral part of the process. How do we foster an environment where we feel comfortable enough to potentially fail, knowing that failure can be the most fertile ground upon which to build meaningful work? And of course, we see budgets for cultural institutions, arts education and programming being cut across the country, including in school curriculums. I don’t think most people comprehend the gravity of this – an arts education has been shown to have positive emotional, social, and academic outcomes for students across the board. So more generally, I think we need more economic support for the arts and culture at every level.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

For the last seven years, I’ve kept a spreadsheet where I note every opportunity and artist call I apply to, the results, and my annual percentage of acceptances and rejections. An obvious result is that I’ve grown a thicker skin and learned to push through a mountain of rejections. But surprisingly, it’s the cumulative rejections that have given me the greatest lessons. They’ve helped me gain a healthier relationship with rejection and encouraged me to constantly reformulate my goals. With each rejection, I find myself grounding myself in my values – asking myself: Why is it that I do what I do? What am I in this for? The pull of the careerist pressure to professionalize the creative process can be so stifling. I try to remind myself to return to exploration, experimentation, and risk taking. It seems like with social media everyone is just showing their wins. In actuality, failure is such a big part of the artistic process and can be such a positive force that can inspire us towards evolution – I think we don’t give it the credit that it deserves.

Contact Info:

Suggest a Story: CanvasRebel is built on recommendations from the community; it’s how we uncover hidden gems, so if you or someone you know deserves recognition please let us know

here.