We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Dayquan Moeller a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Dayquan thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Have you been able to earn a full-time living from your creative work? If so, can you walk us through your journey and how you made it happen? Was it like that from day one? If not, what were some of the major steps and milestones and do you think you could have sped up the process somehow knowing what you know now?

I’m an artist who doesn’t earn a full-time living from my creative work, and I’m okay with that!

I have supported myself with a variety of different gig work from sound designing a theatre production to editing my friends’ writing. Currently I am doing door-to-door canvassing to campaign for better wages for hotel workers in Long Beach. All three of those are gigs that I love, despite them being unrelated to my art practice (at least on the surface, there are more connections than you’d expect).

I had a teacher in high school that would mock guys who missed their “Kobe” shot when trying to throw things into a trash can by telling them – “don’t quit your day job.” I know it was just a joke, but it demonstrates how ingrained in our society this idea is that we must choose between the passion of our “dream job” and the practicality of a “day job.”

There’s a really great article by the composer and writer Max Alper titled “Lifers, Dayjobbers, and the Independently Wealthy: A Letter to a Former Student” that deconstructs this idea quite beautifully. In it he points out that some of the most influential artists of the last century did not rely solely on their art to sustain themselves. For example, John Cage is best known for his music but he supported himself by selling truffles and mushrooms! I highly recommend all artists read the full article, it’s really helped me reject the belief that I must work full time as an artist to be a “real” artist.

I don’t want to romanticize the struggle of not being able to work solely on my art, if I could I would. But I also don’t believe having a “day job” is the death sentence for artists people make it out to be.

I take pride in being a working-class artist.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I specialize in a lower-than-lofi performance art practice, frequently using nothing more than my body, words, and found materials to explore a concept or theme. I am deeply inspired by performance and installation artists of the 90s, in particular those whose work we now describe as relational aesthetics.

My artistic journey began in middle school when my oIder sister, herself an actress and playwright, encouraged me to start writing plays of my own. I very quickly fell in love with the craft, and for a long period in my life wanted nothing more than to be a playwright.

This changed, however, in 2020 when my freshman year of college was forced online by the Covid-19 pandemic. Stuck at home without access to live theatre, I started exploring other creative outlets and eventually discovered a passion for performance art. I was very drawn to the DIY nature of the form, which essentially allowed me to create “micro-plays,” a kind of theatre without the theatre. One work from my nascent performance art era that I am still proud of was called “HELLO/GOODBYE,” in which I walked around my neighborhood with a cardboard box on my head. It was a meditation on how masks and social distancing changed the way we interact with each other in a post-pandemic world.

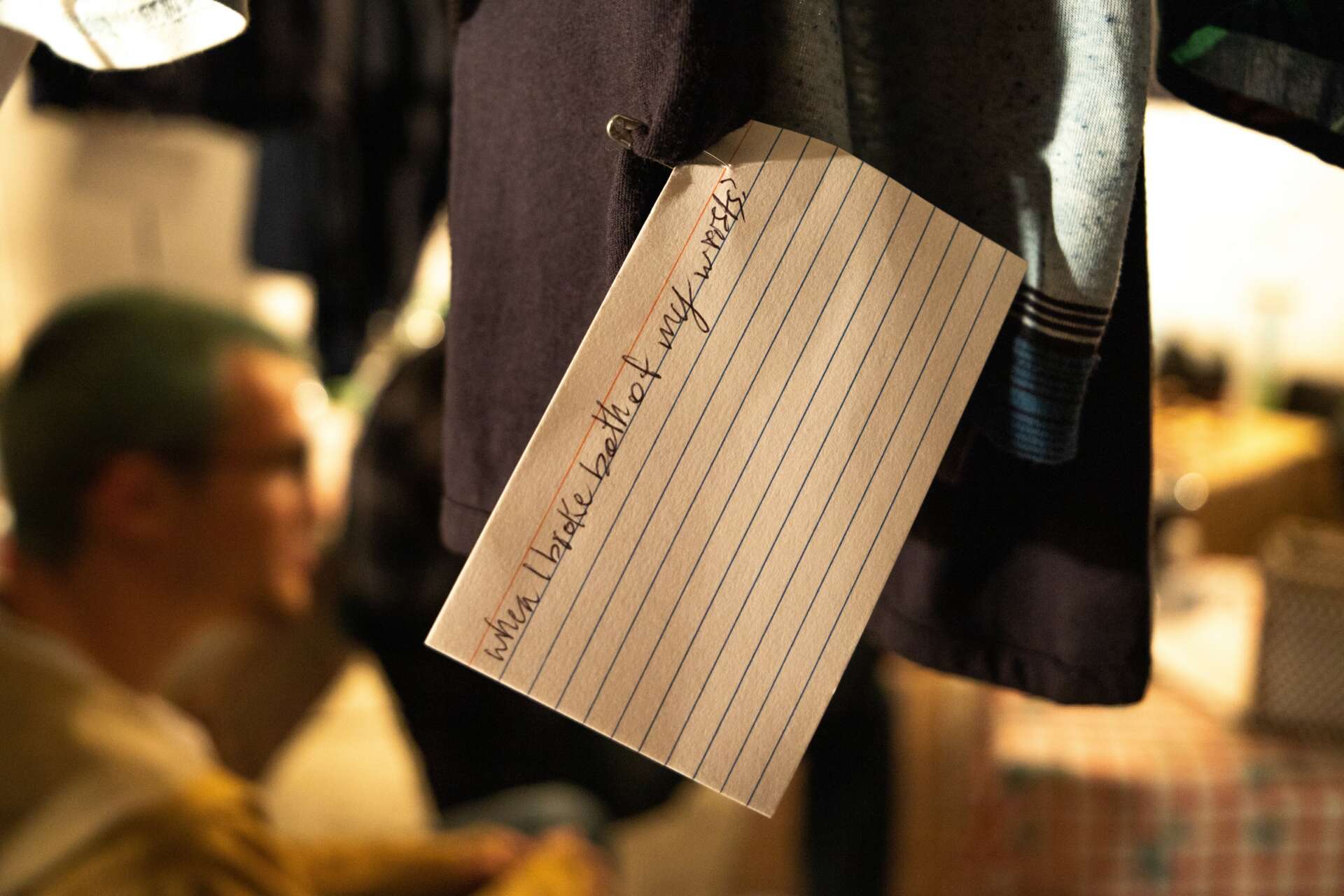

More recently, my performances have expanded to include audience participation. This past October, I took part in a group show titled “This Must Be the Place” with Adept Design in Long Beach. My contribution, titled “BABY BOY/BABY BLUE,” was an interactive performance-installation in which I buried myself under every item of blue clothing that I own. The audience was asked to “free” me by hanging the blue clothes on a clothing line. Once all the clothes were hung up, the audience was asked to write about a time they “felt blue,” and then used diaper pins to attach their responses to the items of clothing. “BABY BOY/BABY BLUE” was a reflection on my own mental health struggles, which often manifests itself as an infamous pile of laundry in my room.

I also have an extended practice in experimental music and sound art. My 2022 composition “Four Corners” featured two trumpeters and two trombonists responding to the sounds of a street intersection. My electronic compostion, “Nostalgia.wav” will debut at Texas Tech University “Electronic Nights” concert series on January 24, 2024.

One of my goals for 2024 is to discover ways I can blend my sound, music, and performance art practices.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

One lesson I had to unlearn was the notion that you have to have a singular passion that will be your career for the rest of your life. As a playwright-turned-performance artist who still dreams of writing a hit play one day, I find the idea of having multiple passions to be very liberating. That by the time we’re 18 we’re supposed to have decided on one singular passion that we will pursue for the rest of our lives is actually quite dystopian when you put it in words.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

I think non-creatives (that is to say people who don’t self-identify as creatives, I believe there is an artist in everyone) struggle to see how art can be useful to them beyond just entertainment. More specifically, I wish activists respected art-making as a legitimate form of protest. I personally know quite a few people who are skeptical of arts activism. This skepticism takes a toll on me as a performance artist interested in social justice, which in turn leads to imposter syndrome. I often ask myself: nothing is worse than a ‘performative activist,’ so how can I dare to call my performance, “activism?”

Nonetheless, I am still confident in the role of art in liberation struggles. After all – corporations spend billions on advertisements and governments have entire departments dedicated to making themselves look good. They’re waging a propaganda war, and our art is how we fight back.

For this reason I’m always trying new ways to bring my art into my activism. Currently, this is manifesting as an obsession with making puppets to bring to protests. It’s definitely something that’s out of my comfort zone as an artist, but I’m getting better at it every time. I hope to see more people, artists and non-artists alike, using their creativity to make a difference. A couple of my friends are making protest puppets too. We’re in our puppet era.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.behance.net/dayquanmoeller

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/dayday_moemoe/

Image Credits

Tahirih Moeller Rosemae Kaiklian